Complete Guide to Virgin Islands National Park including things to do, camping, lodging, how to get to the park, and so much more.

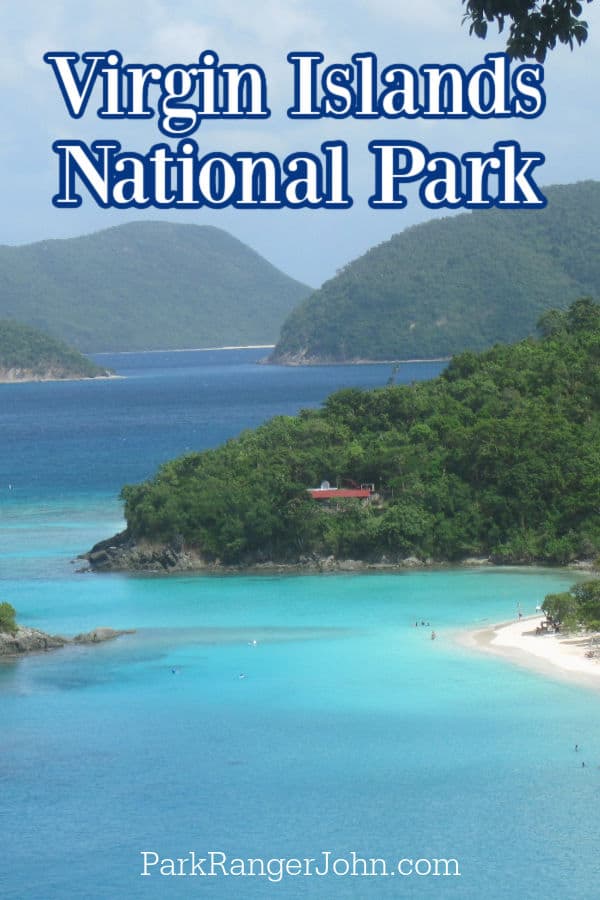

Virgin Islands National Park

For many, a mere mention of that far-off sea conjures up visions of lush tropical islands and bright sun-drenched beaches lines with graceful palms that rustle in the breeze, beaches where lovely turquoise water, warm and soothing, laps gently at the shore.

And what comfort we find in the knowledge that such places do exist!

There are, for instance, the U.S. Virgin Islands, St. Croix, St. Thomas, and St. John, together with many smaller islands and islets, scattered across the deep blue sea just east of Puerto Rico.

And on one of them is found a uniquely beautiful natural treasure, Virgin Islands National Park.

Comprising more than half of the island of St. John and 5,650 acres of adjacent waters, it totals only about 15,000 acres, and so is one of the very smallest of our national parks.

But size alone is no measure of the special quality of a place.

Here we have an island rich in natural beauty and with a varied human heritage. (No other national park can boast a direct historical link with Christopher Columbus.)

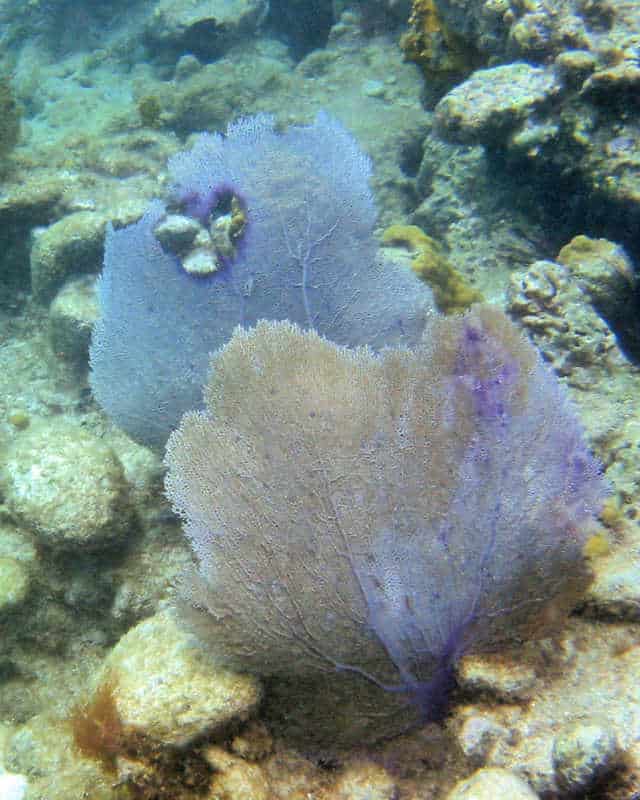

Even more intriguing is the underwater portion of the park, a marine preserve where all can explore the mysteries of the secret realm beneath the sea: coral reefs, broad expanses of white sand, underwater grasslands, each of them teeming with incredibly colorful creatures.

About Virgin Islands National Park

Virgin Islands National Park is a tropical oasis located on the island of St. John in the Caribbean’s Virgin Islands.

The park covers about 60% of the island and is famous for its idyllic beaches, beautiful hiking trails, and some seriously stunning views.

Some of the park’s most popular pastimes include snorkeling, kayaking, exploring the ruins, and simply bumming on the white sand beaches.

Below you’ll find the complete guide to exploring Virgin Islands National Park.

Is Virgin Islands National Park worth visiting?

Although it is a bit far-flung from America’s mainland, Virgin Islands National Park is absolutely worth visiting.

This tropical oasis offers up the perfect combination of tranquility and adventure, and those who make the long journey here are sure to enjoy it.

History of Virgin Islands National Park

Although the island of St. John is famous for being a landing point for Christopher Columbus in 1493, the history of this region predates his arrival by hundreds of years.

Previously, the Taino people populated these islands, and petroglyphs affirming their existence can be found at various places around the island.

By the late 1600s, the Danish laid claim to the islands and began harvesting sugar cane.

Sugar production reached its peak by 1810 but became obsolete when slavery ended in 1848. However, you can still see many of the ruins left by these mills around the park.

The island was purchased by the United States in 1917, and in 1952 Laurence Rockefeller purchased much of St. John and donated it to the U.S. government so it could be established as a national park.

Things to know before your visit to Virgin Islands National Park

Virgin Islands National Park Entrance Fee

Park entrance fees are separate from camping and lodging fees.

Virgin Islands National Park does not charge an entrance fee but there is a fee for Trunk Bay and mooring.

$5.00 - Trunk Bay Day Pass

$2.50 - Trunk Bay Senior Day Pass

$26 - Overnight mooring or anchoring fee

$13 - Senior overnight mooring or anchoring fee.

Learn more about National Park Passes for parks that have an entrance fee.

$80.00 - For the America the Beautiful/National Park Pass. The pass covers entrance fees to all US National Park Sites and over 2,000 Federal Recreation Fee Sites for an entire year and covers everyone in the car for per-vehicle sites and up to 4 adults for per-person sites.

Buy your pass at this link, and REI will donate 10% of pass proceeds to the National Forest Foundation, National Park Foundation, and the U.S. Endowment for Forestry & Communities.

National Park Free Entrance Days -Mark your calendars with the five free entrance days the National Park Service offers annually.

Time Zone

US Virgin Islands observes Atlantic Standard Time all year. There are no Daylight Saving Time clock changes.

Pets

Leashed dogs are allowed on trail. Pets are not allowed on beaches.

Cell Service

Cell service is available but the strength of service will depend on where you are on the islands.

Park Hours

The park is open 24/7. There are specific hours for the visitor center and visitor services.

Wi-Fi

Public Wi-Fi is available at the Visitor Center in Cruz Bay.

Parking

Each of the beaches and trailheads has limited parking. You will want to arrive early in the day to secure a parking spot.

Food/Restaurants

There are a few snack bars available in the park.

Trunk Bay Café and Bar at Trunk Bay

Rain Tree Café at Cinnamon Bay Beach and Campground

Gas

There are no gas stations within the park.

Drones

Drones are not permitted within National Park Sites.

National Park Passport Stamps

National Park Passport stamps can be found in the visitor center.

We like to use these circle stickers for park stamps so we don't have to bring our passport book with us on every trip.

The National Park Passport Book program is a great way to document all of the parks you have visitied.

You can get Passport Stickers and Annual Stamp Sets to help enhance your Passport Book.

Don't forget to pack

Insect repellent is always a great idea outdoors, especially around any body of water.

We use Permethrin Spray on our clothes before our park trips. Please read my article on preventing biting insects while enjoying the outdoors.

Sunscreen - I buy environmentally friendly sunscreen whenever possible because you inevitably pull it out at the beach.

Bring your water bottle and plenty of water with you. Plastic water bottles are not sold in the park.

Sunglasses - I always bring sunglasses with me. I personally love Goodr sunglasses because they are lightweight, durable, and have awesome National Park Designs from several National Parks like Joshua Tree, Yellowstone, Hawaii Volcanoes, Acadia, Denali, and more!

Click here to get your National Parks Edition of Goodr Sunglasses!

Binoculars/Spotting Scope - These will help spot birds and wildlife and make them easier to identify. We tend to see waterfowl in the distance, and they are always just a bit too far to identify them without binoculars.

Details about Virgin Islands National Park

Size - 15,052 acres

Virgin Islands NP is currently ranked at 60 out of 63 National Parks by Size.

Date Established

August 2, 1956

Visitation

In 2021, Virgin Islands NP had 323,999 park visitors.

In 2020, Virgin Islands NP had 167,540 park visitors.

In 2019, Virgin Islands NP had 133,398 park visitors.

Learn more about the most visited and least visited National Parks in the US

National Park Address

1300 Cruz Bay Creek

St. John, VI 00830

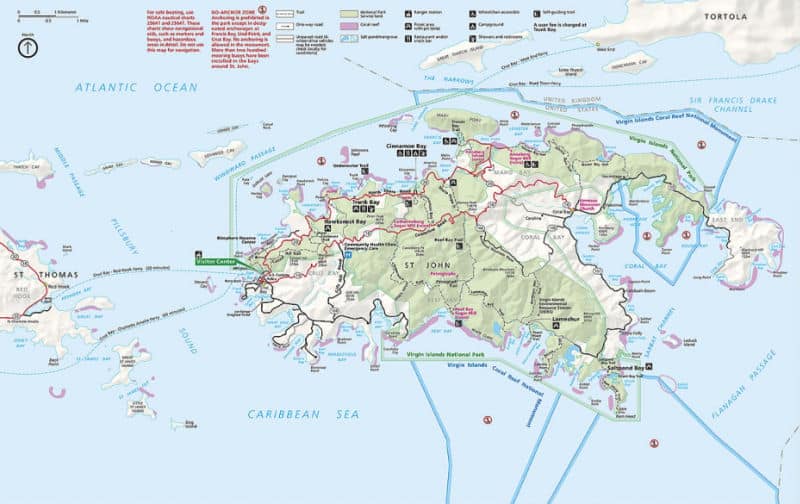

Virgin Islands National Park Map

For a more detailed map we like the National Geographic Trails Illustrated Park map available on Amazon.

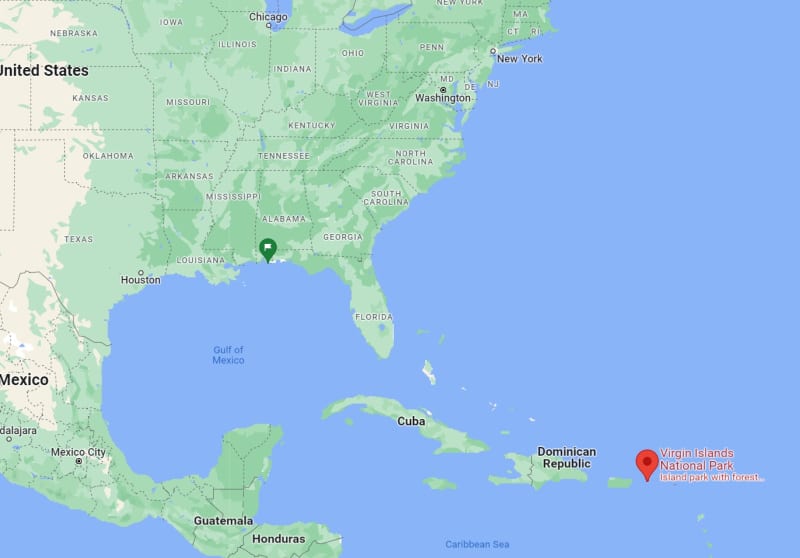

Where is Virgin Islands National Park?

Virgin Islands National Park is located on the island of St. John in the U.S. Virgin Islands of the Caribbean.

Estimated distance from major cities nearby

All major cities will need to be reached via plane or boat transportation.

Estimated Distance from nearby National Park

Each of these parks are located on the mainland of the United States and would be a flight from the Virgin Islands.

Where is the National Park Visitor Center?

The park visitor center is located on St. John

Getting to Virgin Islands National Park

Closest Airports

St. Thomas Cyril E. King Airport (STT)

Driving Directions

Although it’s impossible to drive TO the park, you will need a car to get around the area, as no shuttle options are available.

You can rent a car in St. Thomas before taking the ferry or rent a car in Cruz Bay after you arrive.

You could also hire a “safari-style” taxi service to take you around the park.

Ferry

Most visitors fly into St. Thomas, and from there you will need to take a ferry to the island of St. John, where the park is located. Ferries depart from Charlotte Amalie and Red Hook.

Best time to visit Virgin Islands National Park

The best time to visit the park is between December and April. The weather is great, crowds are at their lowest, and hurricane season is complete.

However, thanks to its tropical temperament, there is truly no bad time to visit Virgin Islands National Park, and each season has its pros and cons.

Weather and Seasons

Spring

Spring is a great time to visit the park. The temperatures are hot, there’s an abundance of sunshine, and hurricanes are rare.

Tourism does begin to pick up a bit over this season, but there are still fewer crowds than in the summer months.

Plane tickets are also relatively cheaper in the spring than in the summer.

Summer

Summer is by far the most popular time to visit the park. The weather is great, but you can expect large crowds and higher prices.

This is also the official start of hurricane season, so watch the weather forecast and be prepared for the worst.

Fall

Fall is a relatively nice time to visit the park. Crowds dwindle, the sun continues to shine, and prices are at their lowest.

If this seems too good to be true, that’s because it is. Autumn is peak hurricane season, and unfortunately, big storms are not uncommon during this time - so travel with caution if you plan a trip for the fall!

Winter

Winter is perhaps the best time to visit Virgin Islands National Park. There are fewer crowds than in the spring and summer, and flights will likely be slightly cheaper.

Temperatures are relatively cooler, but it’s still a tropical island, and sunshine is abundant.

Winter is a great time for surfing on the island thanks to the large swells, but beware that some swimming beaches may be closed if you visit during this season.

Best Things to do in Virgin Islands National Park

Trunk Bay

Trunk Bay is one of the most iconic locations in all of the Caribbean. This stunning bay boasts all the quintessential “idyllic island” attributes, including soft white sand, swaying palm trees, and beautiful turquoise water.

Trunk Bay is also famed for its underwater trail, where snorkelers can see an abundance of vibrant marine life. There are snorkel rentals located here for those who didn’t pack their own gear.

Junior Ranger Program

Visitors both young and old can experience the park in a fun, hands-on way when they partake in the Junior Ranger Program.

You’ll learn all about the park’s history, wildlife, and more, and at the end, you’ll receive a cool badge to add to your collection!

Bird Watching

The island of St. John is phenomenal for bird watching. There are about 144 species that can be seen in the park, 35 of which are full-time residents.

Keep your eyes peeled, and you’ll likely see a lovely combination of forest birds, seabirds, and shorebirds, depending on where you are in the park.

Some of the best places for bird watching include Francis Bay Salt Pond Trail, Cinnamon Bay Nature Loop, and Lameshur Bay.

Snorkeling

The crystal blue waters of the Virgin Islands are famed for their abundance of marine life.

When you snorkel, you’ll get an up-close look at colorful coral reefs, a wide variety of fish, sea turtles, sharks, and more.

Not only is the underwater life incredible, but the warm waters, calm currents, and sheltered bays around the island make snorkeling here a truly incredible experience.

Some of the best places in the park for snorkeling include Waterlemon Cay, Trunk Bay, Hurricane Hole, and Little Lameshur Bay.

Kayaking

One of the best ways to explore the park is by kayak. As you paddle through the azure waters, you’ll likely spot sea turtles, colorful fish, and rays swimming alongside you.

There are several places around the park to rent kayaks, including Maho Bay and Cinnamon Bay.

Beaches

The hardest decision you'll make while visiting the park may well be which beaches to visit.

There are countless sections of soft white sand to hunker down on for a beach day, each one as beautiful as the next.

Some prefer the scenic north shores, while others hunt for solitude among the island's lesser-known beaches.

Below we’ve highlighted a few favorites for you to choose from, but know that your opportunities for a perfect beach day at Virgin Island National Park are truly endless.

Maho Bay

Maho Bay is the most developed beach in the park. Visitors will have access to food trucks, rum huts, and souvenir shops in addition to the beach, though they will also have quite a lot of other visitors to contend with.

Trunk Bay

Trunk Bay is perhaps the most famous beach on the island, if not the entire Caribbean. The beauty and amenities here draw lots of visitors, as does the 600-foot-long underwater trail for divers.

Jumbie Bay

Jumbie Bay is a great option for those looking to escape the crowds. The small parking lot means that only a few vehicles at a time can enjoy this lovely stretch of sand, and the small trail down to the water is also enough of a deterrent for most.

Oppenheimer/Gibney Beach

With just three parking spots, this is another beach that is never overcrowded. However, if you want to be one of the lucky ones to snag one of the three spots, you’ll need to wake up early and make a beeline for the beach.

Hawksnest Bay

This busy spot is another island favorite due to its impeccable views and easily accessible shoreline. The parking lot is just a few steps from the sand, making it easy to lug all your beach day gear to the sand and commence your day of relaxation in a jiffy.

Ruins

The island of St. John has a long and rich history that predates its national park status.

Today, you can explore the ruins of old plantations that once dominated the island.

Most of the ruins look like they’ve come straight out of an Indiana Jones movie, and many also feature fantastic views across the Caribbean.

Some of the best spots to view these beautiful ruins include America Hill, Annaberg Plantation, Reef Bay Sugar Plantation, and Peace Hill Windmill, among others.

Virgin Island National Park Tours

Hiking in Virgin Islands National Park

Always carry the 10 essentials for outdoor survival when exploring.

There are tons of trails around the park, so hikers of all skill levels will be able to find a suitable route. Below we’ve highlighted a few of the park’s best trails.

Peace Hill Trail: Easy - .2 miles - Out & Back

This short, rocky path leads uphill to the Peace Hill Windmill and boasts exceptional views of North Shore bays on either side.

This is a great place to watch the sunset. Average trip time is around 10 minutes.

Cinnamon Bay Nature Trail: Easy - .5 miles - Loop

Situated at the 18th-century Cinnamon Bay Plantation site, the Cinnamon Bay Nature Trail is a short and shaded trek that loops around the ruins and into the forest beyond.

Yawzi Point Trail: Easy - .6 miles - Out & Back

Yawzi Point is a small, thin piece of land situated between Big Lameshur Bay and Little Lameshur Bay.

The trail is mostly flat and offers stunning views of the southern coastline of St. John. Average trip time is around 16 minutes.

Francis Bay Trail: Easy - .7 miles - Loop

This quick and easy trail is a great family-friendly trail, and it’s also popular amongst birders.

The boardwalk leads through a mangrove forest and then leads up to the historic Francis Sugar Factory ruins.

The trail also features sweeping views of Francis Bay and access to a small rocky beach. Average trip time is around 19 minutes.

Drunk Bay Trail: Easy - 1.1 miles - Out & Back

This trail leads you past a salt pond and down to the rocky shores of Drunk Bay, named for its wild and unruly waves.

You likely have this beach to yourself, with the possible exception of a few donkeys. Average trip time is around half an hour.

Ram Head Trail: Moderate - 2.3 miles - Out & Back

If it’s incredible views you seek, then don’t miss Ram Head Trail. The path is mostly exposed, offering hikers uninterrupted views of the stunning south side of Saint John and the Caribbean Sea beyond. Average trip time is around one hour.

Caneel Hill Trail: Moderate - 4 miles - Out & Back

This is one of the most popular trails in the park, thanks to its convenient location near Cruz Bay. The route leads up to Margaret Hill, where hikers will be rewarded with panoramic views of St. John. This is one of the best places in the park to catch one of the island’s colorful sunsets. Average trip time is around 2.5 hours.

Reef Bay Trail: Moderate - 4.4 miles - Out & Back

Reef Bay Trail is another one of the most popular treks in the park. Although it is a bit more strenuous than some of the other trails around the island, it is the perfect way to get a feel for all the park has to offer. You’ll go through two sugar cane forests, past an old mill, and eventually end up at a beautiful secluded beach. You could also add a detour along Petroglyph Trail, where you’ll be able to see ancient rock carvings made by the Taino people hundreds of years ago. Average trip time is around 2.5 hours.

How to beat the crowds in Virgin Islands National Park?

If you want to beat the crowds at Virgin Islands National Park, plan your visit for one of the shoulder seasons.

Spring and Summer see the most park visitors, so fall and winter are your best bet for having this stunning area all to yourself. Beware that hurricane season is at its peak in the fall.

Where to stay when visiting Virgin Islands National Park

Caneel Bay Resort

Caneel Bay Resort has been wowing park visitors since the 1950s. Unfortunately, the resort took on devastating damage during the Category 5 hurricanes back in 2017 and will remain closed for the duration of 2022.

However, restorations are well underway, and you may be able to stay at this beloved resort once again in the near future.

Lodging near the park

The Westin St. John Resort Villas - You can look forward to a poolside bar, a terrace, and a coffee shop/café at The Westin St. John Resort Villas. This resort is a great place to bask in the sun with a white sand beach, beachfront dining, and sun loungers. For some rest and relaxation, visit the hot tub. Enjoy Caribbean cuisine and more at the two onsite restaurants. In addition to a garden and a playground, guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi.

Click on the map below to see the current rates for hotels and vacation rentals on St. John and nearby islands.

Virgin Islands National Park Camping

Cinnamon Bay Campground

Cinnamon Bay Campground is once again up and running after a long hiatus due to hurricane damage. This is the only campground in the park, and sites get booked up relatively quickly.

Campers can choose from bare sites with a tent pad, grill, and picnic table, or upgrade to an eco-tent, group tent, or even an oceanside cottage.

The campground also has food trucks, a breakfast café, and watersport rentals with snorkel gear, kayaks, and paddleboards.

Parks Near Virgin Islands National Park

Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument

Buck Island Reef National Monument

Salt River Bay National Historic Park and Ecological Preserve

Christiansted National Historic Site

San Juan National Historic Site

Check out all of the US Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico National Park sites.

Make sure to follow Park Ranger John on Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, and TikTok