Biscayne National Park was established by Congress in 1968 to preserve and protect the tropical setting, vegetation, and animal life of Biscayne Bay and the upper Florida Keys.

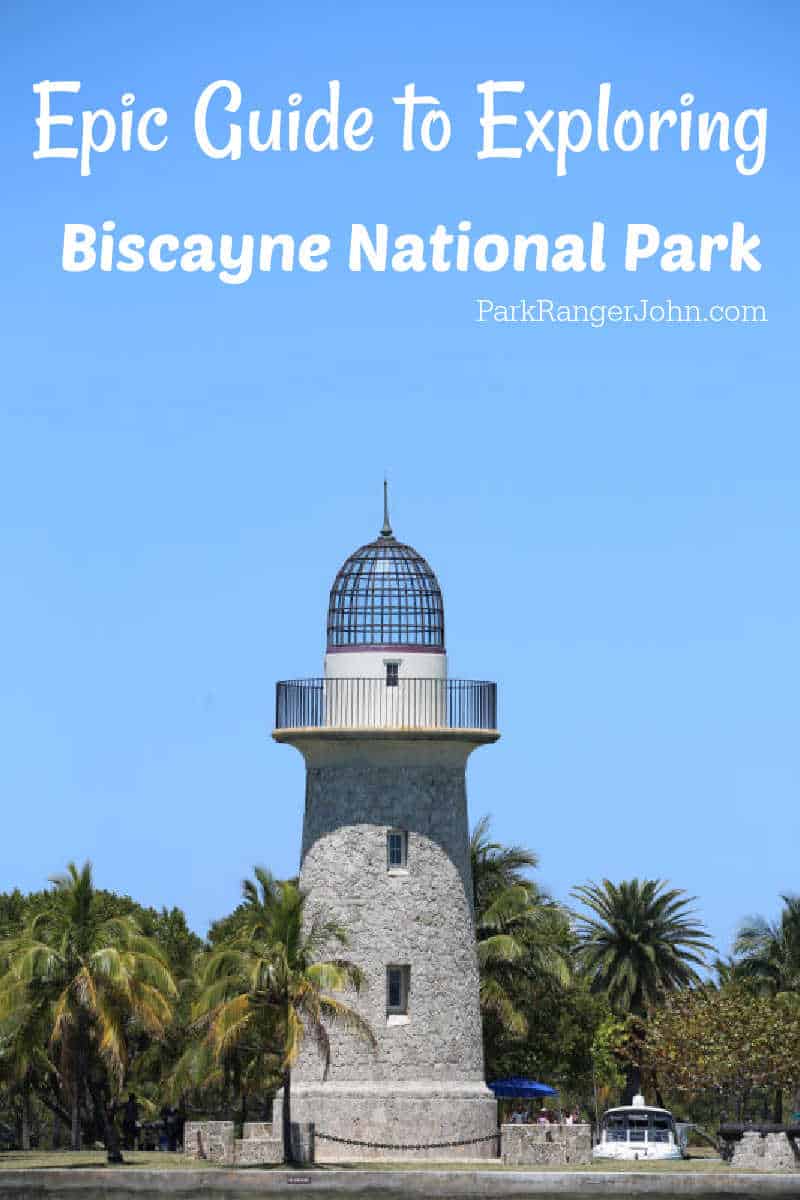

Biscayne National Park

Just south of Miami lies Biscayne National Park. This incredibly unique park is primarily water-based with 95 percent of its area submerged within either the shallow Biscayne Bay or the more turbulent waters of the Hawk Channel and the Florida Straits.

The park’s land area includes 4,825 acres of largely undeveloped mangrove shoreline and 4,250 acres scattered across forty-two keys.

About Biscayne National Park

What makes this place so special is that Biscayne National Park protects four distinct ecosystems that melt into one another creating rich edge communities known as ecotones.

These communities support an incredible array of wildlife including marine life like manatees and sea turtles to hundreds of species of birds and fish, and plants and insects found nowhere else in the United States.

Even more amazing is that it is all just outside one of the nation's largest cities, Miami Florida.

I personally believe that Biscayne is one of the Crown Jewels in the National Park system!

This park protects a large and diverse area filled with endangered and threatened animal and plant species while giving great recreational opportunities for those who visit.

History of Biscayne NP

Pirates once roamed these waters, seeking galleons laden with gold, and even today chests of their buried treasure are discovered now and then.

Ships that were surprised in the night by hidden reefs lie many fathoms deep, their secrets safe with the sharks, spiny lobsters, and crabs that live in Biscayne.

Extending from the thick mangrove forests of the Florida mainland eastward across the South Biscayne Bay, the park–the only underwater national park in the continental United States–reaches beyond a chain of islands to the coral reefs flourishing at the edge of the Gulf Stream.

The Gulf Stream waters flow past the reefs like a gigantic river, their warmth enabling the coral to survive annual invasions of winter weather.

Sea turtles, whales, and great schools of tuna ride the ocean river to new homes, and swept along with them are tremendous numbers of young animals from Caribbean spawning grounds, destined to grow into the adult fish, shellfish, and other marine creatures that populate the reefs of Biscayne National Park.

Mighty stone fortresses besieged by the sea, coral reefs are actually living structures built by millions of soft-bodied, flower-like animals called polyps.

Each little polyp–most are scarcely an eighth of an inch across–nestles within a flower-shaped limestone cup.

By day the fleshy polyps remain safely tucked inside their stony compartments, but at night they protrude to form a whitish fuzz over the surface of the colony, their tiny tentacles reaching out to snatch small bits of food from the water.

Small as they are, polyps are by no means simple creatures. The graceful dancing motions of their tentacles, the intricacy, and symmetry of their bodies, their miraculous ability to take chemicals from the sea and turn them into stone–such complexities can astound those more accustomed to focusing on larger beings.

Remarkably, each little polyp is itself host to other forms of life: a community of algae lives within its tissues, giving and receiving life.

The minuscule green plants absorb carbon dioxide exhaled by the coral, and the coral breathes oxygen produced by the algae during photosynthesis. The relationship works only in shallow water, where sunlight can reach the algae–and only in shallow water will you find living coral.

As new generations of polyps are born, they add layer after layer of limestone to the work of their ancestors, building a colony that may eventually contain millions of polyps.

Each year, the colony lays down a ring of limestone, much as trees produce their annual growth rings. In good years, when there is plenty of food and sunlight and the temperature of the water remains above 68° F, the corals multiply rapidly and the rings are thick. In bad years they are thin.

How big a coral gets varies with the species. Some colonies grow to only a few feet tall; others rise hundreds of feet.

Staghorn and elkhorn corals, their branching shapes reminiscent of the antlers of deer, sometimes grow so large that they shade out the smaller species, creating canyons beneath their "tines."

Reaching these proportions is no short-term achievement: a massive brain coral–some colonies are 15 feet across–may take 30 years to add just an inch to its convoluted girth.

At Biscayne, elkhorns and staghorns form the sturdy backbone of the main reef, creating a barrier that protects the islands from the full force of the sea.

Thousands of miniature reefs, called patch reefs, lie scattered in the shallow water between the outer reef and the islands. Ranging in size from several feet to several hundred, they consist mostly of rounded hills of star and brain corals and the leafy plates of lettuce coral.

The elkhorns and staghorns, unable to tolerate the increased silt and shifting temperatures of the shallows, do not flourish in these quiet places.

Periodically hurricanes and severe winter storms kill part of a reef, leaving the white limestone skeleton to be colonized by barnacles, sponges, algae, and other marine life.

Although this restores a living surface to the coral, the new colonists break the skeleton into smaller chunks and pieces, some of which are ground into grains of sand by pounding surf. The reef illustrates a grand principle: no construction, whether of nature or of man, will last forever.

Is Biscayne National Park worth visiting?

I love Biscayne National Park and YES it is worth visiting!

The key to having a great visit is to get out on the water and go snorkeling or diving, see the lighthouses, and explore the keys!

There is a great visitor center that makes a great first place to visit but don't let the water limit your exploration of this park!

Make sure to take one or more of the many guided tours available and explore this amazing park.

History of Biscayne National Park

Some of Biscayne National Park's cultural resources date back 10,000 years including prehistoric sites providing evidence of aboriginal settlement, historic shipwrecks from the Spanish exploration of the Americas, archeological ruins related to nineteenth and early twentieth-century homesteading, and pioneer settlements.

The most recent history included pineapple farmers and presidents who sought peace and solitude on Adams Key.

Things to know before your visit to Biscayne National Park

Biscayne National Park Entrance Fee

Park entrance fees are separate from camping and lodging fees.

Biscayne National Park does not charge an entrance fee!

Learn more about National Park Passes for parks that have an entrance fee.

$80.00 - For the America the Beautiful/National Park Pass. The pass covers entrance fees to all US National Park Sites and over 2,000 Federal Recreation Fee Sites for an entire year and covers everyone in the car for per-vehicle sites and up to 4 adults for per-person sites.

Buy your pass at this link, and REI will donate 10% of pass proceeds to the National Forest Foundation, National Park Foundation, and the U.S. Endowment for Forestry & Communities.

National Park Free Entrance Days -Mark your calendars with the five free entrance days the National Park Service offers annually.

Time Zone

EST - Eastern Standard Time

Pets

Pets are allowed within Biscayne NP. Pets must be on a leash no longer than 6 feet long.

On Elliott Key pets on a leash are permitted within developed areas only. Pets may not be left unattended. Pets are not allowed in buildings.

Pets, with the exception of service animals, are not allowed on Boca Chita Key including vessels docked at Boca Chita Key.

Cell Service

Cellular service is available but there are areas without coverage that exist throughout the park.

Park Hours

Park waters are open 24 hours a day, all year.

Wi-Fi

Free Wi-Fi is offered at the Dante Fascell Visitor Center; however, the availability and strength of the signal can vary.

Parking

There is a nice size parking area near the visitor center.

Food/Restaurants

There are no restaurants in Biscayne National Park.

Gas

There are no gas stations in the park.

National Park Passport Stamps

National Park Passport stamps can be found in the visitor center.

We like to use these circle stickers for park stamps so we don't have to bring our passport book with us on every trip.

The National Park Passport Book program is a great way to document all of the parks you have visitied.

You can get Passport Stickers and Annual Stamp Sets to help enhance your Passport Book.

Biscayne NP is part of the 2018 Passport Stamp Set

Electric Vehicle Charging

There is an EV Charging Station near the Dante Fascell Visitor Center

Don't forget to pack

Insect repellent is always a great idea outdoors, especially around any body of water.

We use Permethrin Spray on our clothes before our park trips. Please read my article on preventing biting insects while enjoying the outdoors.

Sunscreen - I buy environmentally friendly sunscreen whenever possible because you inevitably pull it out at the beach.

Bring your water bottle and plenty of water with you. Plastic water bottles are not sold in the park.

Sunglasses - I always bring sunglasses with me. I personally love Goodr sunglasses because they are lightweight, durable, and have awesome National Park Designs from several National Parks like Joshua Tree, Yellowstone, Hawaii Volcanoes, Acadia, Denali, and more!

Click here to get your National Parks Edition of Goodr Sunglasses!

Binoculars/Spotting Scope - These will help spot birds and wildlife and make them easier to identify. We tend to see waterfowl in the distance, and they are always just a bit too far to identify them without binoculars.

Details about Biscayne National Park

Size

Biscayne covers 172,971 acres and is currently ranked at 35th out of 63 National Parks by Size

Date Established

Biscayne was established as a National Park on June 28, 1980

Visitation

In 2021, Biscayne NP had 705,655 park visitors.

In 2020, Biscayne NP had 402,770 park visitors.

In 2019, Biscayne NP had 708,522 park visitors

Biscayne National Park Address

9700 SW 328th Street

Sir Lancelot Jones Way

Homestead, FL 33033

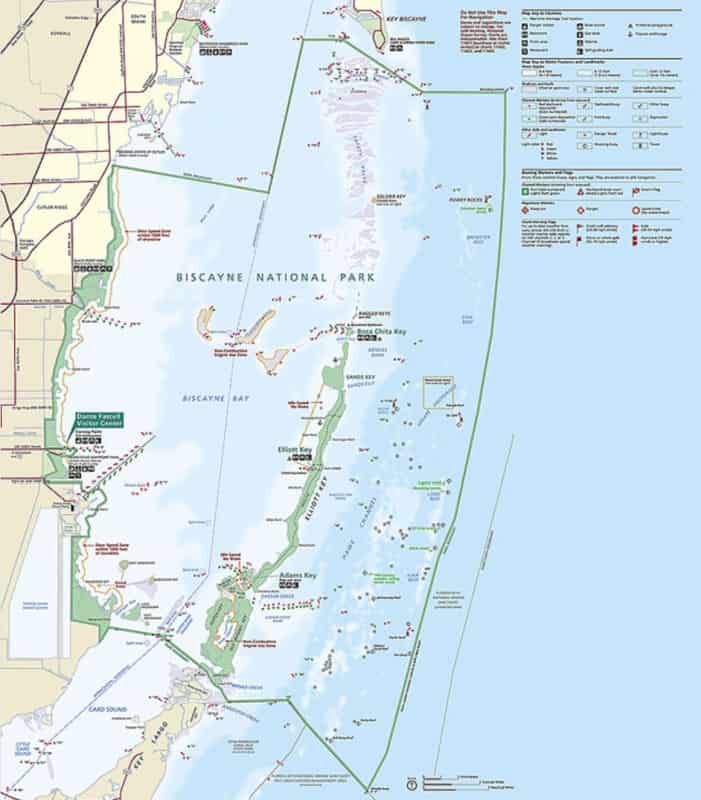

Biscayne National Park Map

Where is Biscayne National Park?

Biscayne NP is located in southern Florida south of Miami. The park covers Biscayne Bay and the upper Florida Keys.

Estimated distance from major cities nearby

Homestead, Florida: 9.5 miles, 17 minutes

Miami Florida: 36 miles, 45 minutes

Tampa, Florida: 295 miles, 4 hours, 30 minutes

Orlando, Florida: 266 miles, 4 hours

Key West, Florida: 133 miles, 2 hours, 45 minutes

Atlanta, Georgia: 693 miles, 10 hours and 15 minutes

Estimated Distance from nearby National Parks

Everglades National Park: 19 miles, 30 minutes

Dry Tortugas National Park: 137 miles, 3 hours from Biscayne National Park to Key West.

You will have to take a boat or a charter plane to Dry Tortugas.

Where is the Biscayne National Park Visitor Center?

The Dante Fascell Visitor Center is located at Convoy Point, 9 miles east of the city of Homestead, Florida.

Getting to Biscayne National Park

Closest Airports

Miami International Airport (MIA) 33 miles, 40 minutes (Miami traffic can vary by the minute, be prepared for traffic jams)

Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport (FLL) 60 miles, 1 hour and 10 minutes

Driving Directions

The Dante Fascell Visitor Center and the main parking lot may be reached from the Florida Turnpike by taking Exit 6 (Speedway Boulevard).

Turn left from the exit ramp and continue south to SW 328th Street (North Canal Drive). Turn left on 328th Street and continue for four miles to the end of the road.

Biscayne National Park's entrance is on the left just before the entrance to Homestead Bayfront Marina.

Best time to visit Biscayne National Park.

Most visitors find Spring as the most desirable time to visit while the winter is a close second. Summer is the least favorite as weather and insects make being outdoors a bit more unappealing.

Biscayne National Park Weather and Seasons

The weather in Biscayne NP varies dramatically depending on the time of year you plan to visit.

Make sure to always check storm warnings during hurricane season and know what is happening in the area.

Spring

Spring is the most desirable time for most visitors to visit Biscayne. The temperatures are starting to rise yet still mostly free of insects and hurricanes. Wildlife viewing is at its peak and it is overall an extremely pleasant time to visit.

Summer

The summer is the least desirable time to visit Southern Florida. The temperatures are at their hottest, there is more humidity, more rainstorms, and the mosquitoes and noseeum's become unbearable.

If that's not enough to deter you then you will be visiting during hurricane season (June 1 through November 30) and will most likely see a reduction in services like fewer guided tours.

Take it from someone who lived in Florida as a kid, I avoid Florida in the summer.

The positive side of visiting in the summer is that hotel rooms will be cheaper as nobody in their right mind wants to visit during this time unless they are from a hot/humid climate.

Autumn/Fall

The fall can be similar to the summer months but just not as drastic as the summer.

Winter

I personally think that winter is the best time to visit Florida as this is the dry season with less than 2" of rainfall/month and the temperatures/humidity is the lowest. It is also a great time to avoid mosquitoes with February probably being the best month. The downfall is that the waters will be cooler if you plan on snorkeling/scuba. you will also find larger crowds.

Best things to do in Biscayne National Park

Visit the Dante Facell Visitor Center

The visitor center is located by the parking lot on the mainland. From here you can take the easy Jetty Trail, boat tours from the Biscayne National Park Institute, and tour the visitor center.

There is a 20-minute park video, numerous interpretative and touch displays, and the Biscayne National Park Institute is connected to the visitor center.

Biscayne National Park Snorkeling trip

Did you know that the Florida Straits, the third-largest barrier reef in the world, begins around Miami and extends south to The Florida Keys?

This, along with the shallow Biscayne Bay and the waters of the Hawk Channel make up Biscayne National Park and its four ecosystems teeming with fish.

The Maritime Heritage Trail is a must for those who like to snorkel/dive!

This mapped trail gives park visitors the opportunity to explore the remains of some of the park's many shipwrecks.

Six wrecks have been mapped and the newest addition to the trail is the Fowey Rocks Lighthouse. Check at the visitor center for more information.

Guided Tours

The Biscayne National Park Institute has numerous tours to choose from including snorkeling/scuba, guided paddle trips through Jones Lagoon, Historic Stiltsville tours, Tours to Boca Chita Key, Adams Key, and Elliott Key. and evening sunset cruises!

Make sure to plan ahead to see which tours are offered during your visit and advanced reservations are highly recommended as tours do fill up. You can go online, call ahead at (786)335-3644, or by stopping at the park store.

There is a small boat tour out of Miami that visits Stiltsville and other epic places in Biscayne Bay.

Wildlife watching and Bird Watching

The park is home to an incredible diversity of tropical/subtropical animals and plants including over 500 species of reef fish, a suite of neo-tropical water birds and migratory habitat, and approximately 20 threatened and endangered species.

Hiking at Biscayne National Park

There is a handful of trails at Biscayne National Park. I would consider all of these trails easy as they are all pretty much flat and typically about a mile in total length except for the Spite Trail which is approximately 7 miles one way.

I would not necessarily promote the Spite Trail as it was a road that someone plowed in illegally in spite and not necessarily a pretty hike, especially when the magic of Biscayne is on the water.

The most popular and scenic trail in the park is the Jetty Trail. Half of the trail is a boardwalk trail and the rest is a sand/gravel surface. The trail is eight-tenths of a mile roundtrip with beautiful flowers and a mangrove-lined shoreline that leads to the Colonial Bird Protection Area at the end of a jetty.

Boca Chita Key has a nice six-tenths of a mile round trip loop trail, Adams Key has a half-mile loop trail and Elliott Key has a one-mile loop trail.

Junior Ranger Program

The Junior Ranger Program can be picked up at the visitor center. This is a great way for visitors of all ages to learn more about the park.

How to beat the crowds in Biscayne?

The best way to beat the crowds is to visit in the summer. The downside of visiting in the summer is that there will be fewer tours and will require a little more planning.

Biscayne National Park Lodging

There are no National Park Lodges in Biscayne National Park.

TownePlace Suites by Marriott Miami Homestead - A free breakfast buffet, dry cleaning/laundry services, and a gym are just a few of the amenities provided at TownePlace Suites by Marriott Miami Homestead. Free in-room Wi-Fi and a business center are available to all guests.

Ritz-Carlton Key Biscayne - Take advantage of a terrace, shopping on site, and a garden at The Ritz-Carlton Key Biscayne, Miami. With a beachfront location, beach cabanas, and sun loungers, this resort is the perfect place to soak up some sun. Free Wi-Fi in public areas is available to all guests, along with dry cleaning/laundry services and a bar.

Courtyard by Marriott Miami Homestead - At Courtyard by Marriott Miami Homestead, you can look forward to a grocery/convenience store, a coffee shop/café, and a library. The onsite restaurant, The Bistro, features light fare. In addition to dry cleaning/laundry services and a bar, guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi.

Quality Inn Miami South - free to-go breakfast, a rooftop terrace, and a coffee shop/café. Be sure to enjoy a meal at Dapple Bar and Kitchen, the onsite restaurant. In addition to a garden and dry cleaning/laundry services, guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi.

La Quinta Inn & Suites by Wyndham Miami Cutler Bay - free continental breakfast and laundry facilities. Guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi.

There are several hotels available in the town of Homestead, Florida just 10 miles away. Click on the map below to see additional lodging and vacation rental options.

Biscayne National Park Camping

There are two campgrounds in Biscayne National Park, both are on islands.

Boca Chita Key is the park's most popular island. It features beautiful waterfront views, a grassy camping area, picnic tables, and grills. Toilets are available, but there are no showers, sinks, or drinking water.

Elliott Key is the park's largest island. Restrooms with sinks and cold water showers, picnic tables, and grills are available. Drinking water is available, but bring water as a precaution if the system goes down.

Campsites are available on a first-come, first-served basis.

The only group campsite is located on the ocean side of Elliott Key about a third of a mile from the main campground and restrooms.

It is available for groups of 10 or more by reservation only (786-335-3609).

Fees are $35 per night.

This includes docking for one boat and one tent site for up to six people.

For every additional one to six people in the group arriving on the same vessel, there is a $25 fee.

There is a maximum of thirty people and five tents for this site.

For a fun adventure check out Escape Campervans. These campervans have built in beds, kitchen area with refrigerators, and more. You can have them fully set up with kitchen supplies, bedding, and other fun extras. They are painted with epic designs you can't miss!

Escape Campervans has offices in Vancouver, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Denver, New York, and Orlando

Parks near Biscayne National Park

Make sure to check out all of the Florida National Parks along with National Parks in Georgia, Alabama National Parks, Florida National Parks, Tennessee National Parks, and South Carolina National Parks

There are quite a few National Parks in the Southeast US

National Park Service Website

Make sure to follow Park Ranger John on Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, and TikTok