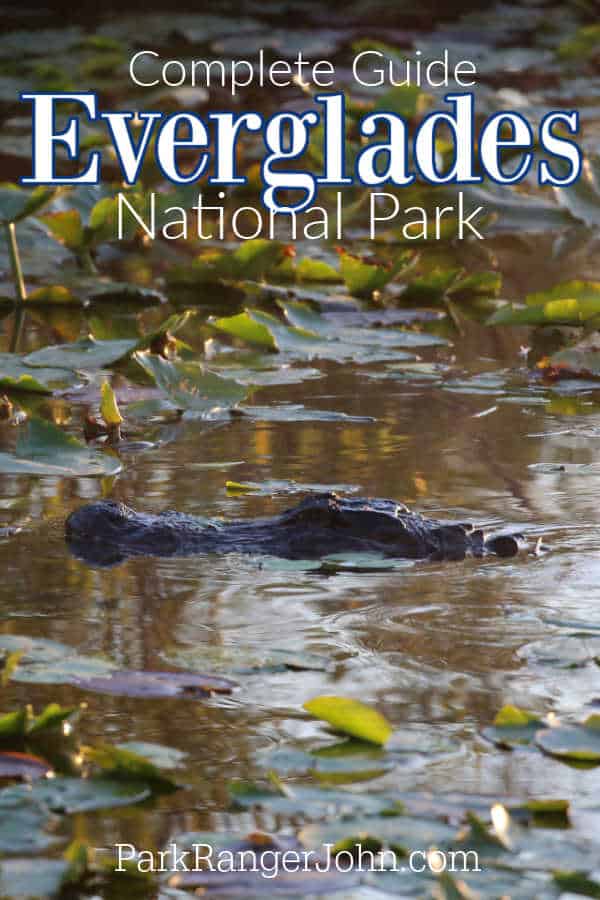

Epic Guide to Everglades National Park in Florida includes things to do, lodging, camping, wildlife, gators, and so much more.

Everglades National Park

The untouched nature with a single road from Miami has fascinated people for decades. If you don’t mind south Florida weather and love looking out for wildlife, this is a place for you to visit.

When coming to the park make sure to be prepared, with enough water, incest repellent, and binoculars.

Everglades is famous as the "River of Grass", which consists of subtropical wilderness with authentic flora and fauna. It is one of the largest wetlands in the world.

About Everglades National Park

The Everglades, a 1.5 million-acre marsh in south Florida, is the third-largest national park in 48 lower states. This National Park has three entrances, none of which are linked; they are all located in various parts of South Florida.

Its unique combination of salt and freshwater offers crucial habitat for a variety of endangered plants and animals, it acts as one of the most important migration corridors, and it is home to the Western Hemisphere's biggest mangrove ecosystem.

Short treks off the main park road lead to this marshy wilderness, or visitors may paddle along the spectacular 99-mile Wilderness Waterway Trail to explore the park's western shore.

Though it may appear to be a long way away, this world-renowned park is only a short drive from Miami.

Every year, at least a million visitors from all around the globe visit the Everglades.

Is Everglades National Park worth visiting?

YES! This is one of my favorite parks to visit in the entire national parks system!

It is a photographer's dream, bird watchers love the variety of birds seen here and there is plenty of activities to do including hiking, kayaking and even taking boat-operated tours of the park.

Whatever you decide to do here, you will have a great time exploring the river of grass at Everglades National Park.

History of Everglades National Park

South Florida's water used to flow from the Kissimmee River to Lake Okeechobee, then southward throughout Biscayne Bay, the Ten Thousand Islands, and Florida Bay.

A patchwork of sawgrass marshes, hardwood hammocks, ponds, sloughs, and wooded uplands grew out of this shallow, slow-moving sheet of water that covered about 11,000 square miles.

This sophisticated system evolved over thousands of years into a perfectly balanced ecosystem that served as the biological infrastructure for the state's southern half.

The Everglades, on the other hand, were seen as viable farmland and settlements by early colonial immigrants and developers.

By the early 1900s, the drainage process had begun to turn the swamp into developable land. The ecology and the animals that depend on it would be gravely harmed as a result.

Everglades National Park was founded in 1947 with the help of many early environmentalists, scientists, and other activists to preserve the natural landscape and avoid further deterioration of its land, vegetation, and wildlife.

Although the Everglades' allure has arisen mostly from its unique ecology, the Everglades' appealing human tale is intricately linked with its unending marshes, dense mangroves, towering palms, alligator holes, and tropical animals.

Things to know before your visit to Everglades National Park

Everglades is much bigger than what people can imagine before first time visiting the area. It is important to have all the information before your trip and to be prepared.

Plenty of sunscreen is not the only thing you need to pack, so make your list ahead of time.

Entrance fee

7-day single-vehicle park pass - $30

7-day individual park pass - $15

7-day motorcycle park pass - $25

Annual Park Pass - $55

Valid for one year through the month of purchase. Admits one private, non-commercial vehicle or its pass holder.

Planning a National Park vacation? America the Beautiful/National Park Pass covers entrance fees for an entire year to all US National Park Sites and over 2,000 Federal Recreation Fee Sites.

The park pass covers everyone in the car for per vehicle sites and for up to 4 adults for per-person sites.

Buy on REI.com and REI will donate 10% of pass proceeds to the National Forest Foundation, National Park Foundation and the U.S. Endowment for Forestry & Communities.

Learn more about National Park Passes for parks that have an entrance fee.

Free Entrance Days -Find the five free entrance days the National Park Service offers annually.

Time Zone

EST - Eastern Standard Time

Pets

Pets are allowed in limited areas within Everglades NP.

Pets must be kept on a leash less than 6 feet in length,

Pets are permitted in the following areas:

- Roadways open to public vehicular traffic

- Roadside campground and picnic areas

- Maintained grounds surrounding public facilities and residential areas

- Private boats

Pets are NOT permitted in the following areas:

- All trails - boardwalk, paved and unpaved

- Unpaved roads

- Shark Valley Tram Trail/Road

Please always keep in mind that the Everglades are filled with wildlife including alligators who have been known to prey on dogs.

Cell Service

According to Signal Checker, all cell phone services are spotty, but T-Mobile and Verizon seem to work better than others. However, in Flamingos campground AT&T was noticeably better than other services.

Park Hours

The park is open year round.

Wi-Fi

Wi-Fi is available at visitor centers, but it is no guarantee, however, most lodging/camping facilities have their own Wi-Fi.

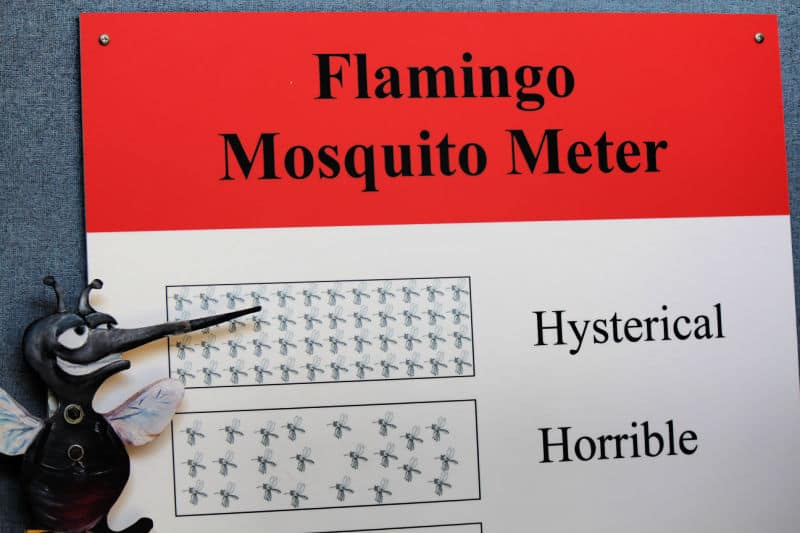

Insect Repellent

Insect repellent is always a great idea when outdoors, especially if you are around any body of water.

Now if the park's visitor center has a mosquito meter sign posted on Hysterical, I would highly consider insect repellent or indoor activities, just saying!

We use Permethrin Spray on our clothes before our park trips.

Water Bottle

Make sure to bring your own water bottle and plenty of water with you. Plastic water bottles are not sold in the park.

Parking

There is a nice size parking lots at most of the trailheads and visitor centers.

Food/Restaurants

There are limited snacks and beverages sold at the visitor centers.

There is a food truck in Flamingo sometimes.

We highly suggest picking up snacks and drinks before heading into the park.

Gas

At Flamingo fuel (gas and diesel) is available for boats and vehicles.

Drones

Drones and other unmanned aircraft are not allowed in the park, or any other National Park Service site.

National Park Passport Stamps

National Park Passport stamps can be found in the visitor center.

Make sure to bring your National Park Passport Book with you or we like to pack these circle stickers so we don't have to bring our entire book with us.

Everglades NP is part of the 1997 Passport Stamp set.

Electric Vehicle Charging

There are EV Charging Stations located at the Ernest Coe Visitor Center, Flamingo, and Shark Valley

Details about Everglades National Park

Size - 1,400,539 Acres

Everglades NP is currently ranked at 10 out of 63 National Parks by Size.

Total acreage including expansion (land and water): 1,542,526 acres (64,238 hectares; 2,410 square miles), in Miami-Dade, Monroe, and Collier Counties.

Designated Wilderness: 1,296,500 acres (524,686 hectares); Potential Wilderness: 81,900 acres (33,144 hectares); for a total of 86% of the total park area.

Everglades Expansion Act added East Everglades (109,500 acres / 44,315 hectares) to the park on December 13, 1989.

Date Established

Everglades National Park was founded on December 6, 1947, dedicated by President Harry S Truman at Everglades City.

"Not often in these demanding days are we able to lay aside the problems of the time, and turn to a project whose great value lies in the enrichment of the human spirit. Today we make the achievement of another great conservation victory. We have permanently safeguarded an irreplaceable primitive area. We have assembled to dedicate to the use of all people for all time, the Everglades National Park."

Here are no lofty peaks seeking the sky, no mighty glaciers or rushing streams wearing away the uplifted land. Here is land, tranquil in its quiet beauty, serving not as the source of water, but as the last receiver of it. To its natural abundance we owe the spectacular plant and animal life that distinguishes this place from all others in our country.

President Harry S Truman, address at the Dedication of Everglades National Park, December 6, 1947

It is now an international asset that attracts tourists from all over the world 70 years later.

The park was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site on October 26, 1979.

Everglades and Dry Tortugas were jointly designated as an International Biosphere Reserve on October 26, 1976.

The park is also designated as a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance on June 4, 1987.

Visitation

In 2021, Everglades NP had 942,130 park visitors.

In 2020, Everglades NP had 702,319 park visitors.

In 2019, Everglades NP had 1,118,300 park visitors.

Learn more about the most visited and least visited National Parks in the US

Everglades National Park Address

40001 State Road 9336, Homestead, FL 33034

Everglades National Park Map

Credit - National Park Service

For a more detailed map we like the National Geographic Trails Illustrated Maps available on Amazon.

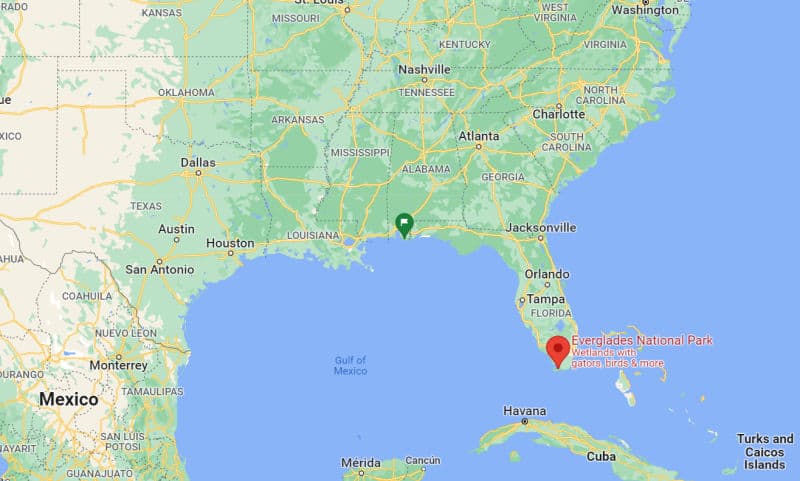

Where is Everglades National Park?

Everglades National Park is located in south Florida and has three entrances in three distinct cities.

It covers a total of 1,509,000 acres across Miami Dade, Monroe, and Collier counties. The Everglades require a car since the distances are great and there is no public transit within the park.

Estimated distance from major cities nearby

Distance is calculated to the Ernest F. Coe Visitor Center

Miami, FL - 49 miles

West Palm Beach, FL - 106 miles (Check out top things to do in West Palm Beach)

Tampa, FL - 309 miles

Orlando, FL - 276 miles

Key West, FL - 134 miles

Atlanta, GA - 704 miles

Estimated Distance from nearby National Parks

Biscayne National Park - 18 miles

Dry Tortugas National Park - 134 miles to Key West and then a boat or seaplane ride to the island

Congaree National Park - 665 miles

New River Gorge National Park - 977 miles

Mammoth Cave National Park - 1,042 miles

Where is the Everglades National Park Visitor Center?

Because of its size, this national park has four visitor centers.

Flamingo Visitor Center

At the Flamingo Visitor Center, you will find informational booklets, educational exhibits, and wilderness permits. Near the visitor center are a public boat ramp, a marina store, campgrounds, and several hiking and canoeing paths.

Prepare ahead of time for food and other necessities, as there are few services accessible. The only available eatery is the Buttonwood Café, or you can pick up basic supplies at the marina.

Visitors entering Flamingo through the main entrance or by boat should pack enough food and drink.

Ernest Coe Visitor Center

The Ernest Coe Visitor Center is open 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Educational exhibits, orientation videos, and informational pamphlets are available. Local artists' special collections are frequently on the show.

In the adjacent bookshop, you may buy books, movies, postcards, and bug repellants. Only a short drive from the tourist center are several popular walking routes. There are restrooms available.

Shark Valley Visitor Center

Educational exhibits, a park movie, and informational pamphlets are available at the Shark Valley Visitor Center. In the gift shop, you may buy books, postcards, and other mementos.

Shark Valley Tram Excursions, Inc. offers guided tram tours, bicycle rentals, refreshments, and soft drinks. Off the main route, there are two short walking trails (one accessible) for your leisure. There are restrooms available.

Gulf Coast Visitor Center

The Gulf Coast Visitor Center is the starting point for exploring the Ten Thousand Islands, a maze of mangrove islands and canals that stretches from Flamingo to Florida Bay and is only accessible by boat in this part of the world.

Educational exhibits, orientation videos, informational booklets, and wilderness camping permits are all available at the visitor center. The park's authorized concessioner may provide boat excursions and rentals.

There are restrooms available. Nearby are restaurants, shopping, accommodation, and camping.

Getting to Everglades National Park

Closest Airports

Miami International Airport (MIA) - 62 miles

International Airports

Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport (FLL) - 96 miles

Palm Beach International Airport (PBI) - 143 miles

Regional Airports

Charlotte County Airport (PGD) - 135 miles

Opa-Locka Executive Airport (OPF) - 53 miles

Driving Directions

Directions to Ernest F. Coe Visitor Center

From Miami - Take the Florida Turnpike (Route 821) south until it ends, merging with U.S. 1 at Florida City. Turn right at the first traffic light onto Palm Drive (State Road 9336/SW 344 St.) and follow the signs to the park.

From Key West - Visitors driving north from the Florida Keys on U.S. 1 should turn left on Palm Drive (State Road 9336/SW 344 St.) in Florida City and follow the signs to the park.

Best time to visit Everglades National Park

The dry season, which runs from early December to early April, is the greatest time to explore the Everglades.

This is a wonderful time to visit since the weather is pleasant, there are fewer mosquitoes, and there are more opportunities to see animals. During the dry season, though, popular Everglades sites might get congested.

Weather and Seasons

Everglades is unique because it has two different seasons: dry and rainy. The dry season is usually from December to April, while the wet season is from May to November, but every year this can differ.

Because of the mild winter temperatures, the park is home to the biggest diversity of wildlife during the dry season. That is why visitors also come at this time of the year. The wet season has more rain and can result in a large number of mosquitoes.

Many programs led by rangers are not offered during the wet summer season due to lower visitor numbers, but other guided tour choices are still available.

Spring

In the Florida Everglades, spring signals the start of the rainy season. November through April is traditionally the dry season. The rainy season, on the other hand, lasts from May to October.

The Everglades' natural splendor comes to life during the wet season, but there's something fresh to admire at any time of year.

Summer

The delicate ecology is ideal for outdoor enthusiasts, adventurers, and eco-tourists in the summer. They can enjoy hiking and kayaking while observing wildlife and impressive plants.

However, the summer months of May through September are the Everglades' off-season when the temperatures are at their highest, and summer rains can swell the rivers.

Autumn/Fall

The Florida Everglades is especially beautiful in the fall. The water levels are lower, leaves have wonderful colors, and wildlife activity is higher.

Also, this is the time of the year with fewer tourists, as the winter season in the park hasn't started yet, but the summer season is already over.

Winter

Winter is the best time to visit the park, with fewer insects, lower temperature and humidity, and overall more things to do. Many great tours are offered at this time, and you should book them in advance if you plan to go there for vacation.

January is the coldest month in the Everglades with a temperature around 77 degrees Fahrenheit. There are no mosquitos at this time, unless it rains then you might find them deeper in the park.

Best Things to do in Everglades National Park

With so many activities to do at Everglades National Park, picking just a handful for your trip might be challenging.

In the Everglades, there are many outdoor activities and energetic things to do, such as hiking, kayaking, animal viewing, and so much more. You can stay in the park overnight camping or staying in a neighboring town and visiting on a day trip.

This location is ideal for nature enthusiasts, families looking to spend time together in the outdoors, and anybody seeking adventure.

Wildlife viewing

In the Gulf Coast Area, the only way to observe animals is by boat. You can kayak the backcountry rivers and creeks, but the animals become sparse as you enter the deep woods.

As a result, you're more likely to see them in more open regions, such as along Chokoloskee Bay's shoreline or on the bigger stretches of rivers. Alligators like riverbanks without mangroves where they can sun, and huge birds must be able to fly freely.

Unless you possess a boat, the best method to view wildlife is on a boat excursion operated by an official concessionaire based at the Gulf Coast Visitor Center.

You won't have to worry about paddling on a guided expedition, and you may take as many photos as you want. The animals are generally long gone by the time you set down your paddles and grab out your camera in a canoe or kayak.

The 10,000 Islands Boat Tour takes you to Chokoloskee Bay, where you may see dolphins and manatees. You'll also see a lot of aquatic birds, as well as a Bald Eagle if you're lucky.

Seasons and weather have an impact on everything in nature. Each month offers its own set of animal watching possibilities, some of which last for weeks or months.

In Florida, wildlife viewing takes tact, patience, and time. There's no assurance that wild creatures and nature will keep to their usual seasonal schedules. Everything changes, even if just for a few weeks, if it has been extremely rainy or cold.

But that's part of the fun, and it adds to the enjoyment of watching wildlife and the environment.

Swamp Tromp in the Everglades, manatees, and breeding bald eagles are among the January hotspots. Visit Lake Apopka North Shore in central Florida, which is the state's greatest inland birding location.

Manatees, Everglades swamp tromping, breeding bald eagles are still at their peak in February.

Visit South Florida to see nesting roseate spoonbills or marvel at the spectacular display of spring wildflowers in March.

Some of Florida's most beautiful species, such as ospreys and red-cockaded woodpeckers, are breeding during May.

Loggerhead turtles are breeding on Florida's east coast beaches in June. One of nature's most spectacular spectacles is the nesting process.

The months of July and August are ideal for seeing sea turtles. In general, it's just too hot and humid to do anything else.

In September fall hawk migration begins, and it's a great time to see the small Key deer.

October is reserved for Monarch butterflies that flock to Florida, as the state's foliage begins to change color.

Manatees begin to congregate around warm water springs in November. The earliest arrival of wintering ducks

Birds are the major topic of December's hotspots. Observe wintering ducks up close. Alternatively, join the Audubon Society's Christmas Bird Count.

There is a great Everglades Naturalist kit that includes a Pocket Naturalist Guide and National Geographic Map.

Junior Ranger Program

If your little ones decide to join the Junior Ranger Program in National Park, they will be introduced to a variety of hands-on, guided, and self-directed activities.

Junior Ranger Programs are designed to immerse children and their families in the National Park experience, cultivating future generations of park stewards and explorers.

Everglades National Park, Biscayne National Park, and Big Cypress National Preserve are all covered by the Junior Ranger book, which is available in English, Spanish, and Haitian Creole.

You may purchase books at any tourist center or online, and get your kiddos excited about the trip.

Purple Gallinule, Anhinga Trail, Everglades National Park, Florida

Bird Watching

The Everglades is largely a 6 inches deep shallow plain of sawgrass, which is suitable for wading birds.

The water is full of algae and bacteria that are great for snakes, turtles, fish, and insects, all of which feed the amazingly diverse bird population.

There are over 2,000 distinct plant species in the park, aside from 51 reptile species, 17 amphibians, 40 mammals, and 347 different species of birds.

During the winter dry season, birds congregate mostly around permanent sources of water, making them relatively simple to watch. This is, without a doubt, the ideal time of year to go birding.

Just 2 miles from the entrance, on the left, lies Royal Palm Hammock. The park's single most popular route, the half-mile Anhinga Trail, is named after one of Florida's most unique birds.

The paved route leads to a boardwalk that cuts through a sawgrass prairie. Look for least bittern, sora, smooth-billed ani, and great white heron along the trip.

By February, the birds should be congregating near Paurotis Pond and Nine-Mile Pond. Both are ideal places to see herons, bald eagles, short-tailed hawks, osprey, and the roseate spoonbill, which many believe to be the Everglades' signature bird.

Look for a spoonbill in Mrazek Pond near Flamingo if you don't see one at Paurotis or Nine Mile Pond.

During the day, migratory and resident cormorants, swallow-tailed kites, Caspian terns, and mottled ducks, may be seen around the ponds; early and late, seek for limpkins and white-crowned pigeons.

The American pintail duck, shoveler duck, widgeon, ruddy duck, scaup duck, and teal duck have all been known to frequent West Lake.

Late in the day, the white-crowned pigeon can be seen flying over the lake. Take a trip along Mangrove Trail's boardwalk to see a large number of American coots.

Mrazek Pond might be one of the greatest sports in the park for bird photography when the water levels are low. There are numerous diverse species in the area. The hordes of birders sometimes make it difficult to spot the birds due to the easy access.

There is a great Everglades folding bird guide with color photos that works great for identifying birds in the park.

Boat Tours

There are two different boat tours offered in the park. Tickets for boat tours can be purchased at the marina.

Backcountry Boat Tour

A guided tour of Everglades National Park's Flamingo Area backcountry lakes is offered by a National Park Service authorized concessionaire. This trip, known as the Backcountry Boat Tour, takes you up the Buttonwood Canal and over Coot Bay to the mouth of Whitewater Bay.

From November to May, the trip runs every day and lasts 1.5 hours, so plan on coming a little early, buying your ticket, and so on. Seeing an American crocodile is a highlight of this tour, but it is never a guarantee.

Florida Bay Boat Tour

This 90-minute trip departs from Flamingo Marina and takes you around Florida Bay. A naturalist will talk about the local birds and sea life, as well as the history of Flamingo and the neighboring keys.

The Florida Bay tour vessel is a double-deck catamaran that offers tourists breathtaking vistas. While no two excursions are the same, and the landscape varies from day to day, ospreys, wading birds, dolphins, manatees, sea turtles, and beautiful sunsets are all possible sightings on this trip.

Airboat Tours

The Everglades is a magnificent environment composed of marshes, woodlands, and mangroves, and the diverse habitat is home to alligators, turtles, manatees, and other creatures.

The best way to see this unique setting is by airboat. Three authorized concessionaires inside the park are located along the Tamiami Trail (Coopertown, Everglades Safari Park, and Gator Park).

At Coopertown, skilled airboat guides will take you on a customized, instructive airboat tour of this unique area. You will pass through the "River of Grass", then through Hardwood Hammock Everglades National Park, stopping at alligator holes and witnessing the abundant wildlife of the Everglades.

At Everglades Safari Park, you can sign up for a private family-friendly tour with an experienced tour guide that will tell you everything about the surroundings. This 30-40 minutes tour also includes a wildlife nature show afterward, and the opportunity to visit Jungle Trail, observation platform, and other exhibits.

Gator Park offers group and private airboat tours that will take you close to alligators. Many of the animals you'll see on your airboat trip are native to the Everglades National Park. You'll see Florida in a way that few others do, from endangered birds that can't be found anywhere else to little critters that dwell among the wild alligators.

Three authorized concessionaires inside the park located along the Tamiami Trail (Coopertown, Everglades Safari Park, and Gator Park).

There is also an small group kayak eco tour available.

Shark Valley Tram Tour

Everglades National Park offers a variety of activities from the park's Shark Valley Visitor Center, including The Shark Valley Tram ride, which is approximately two hours long.

This trip takes you to a viewpoint from where you can see across the Everglades. Along the walk, your naturalist guide will point out important features of the park.

The Shark Valley Visitor Center is located at the park's north entrance. Adult tickets are $27. Book your tour in advance, because it can get quite busy in the season.

Fishing

Fishing in the Everglades provides an experience unlike any other. People come from all over the world to enjoy some of the most exhilarating, adventurous, and mind-boggling fishing possible.

The Everglades contains a diverse range of environments, including fresh, salt, and brackish water. As a result, depending on where you travel, you can find a wide variety of different species.

Whether you're fishing the rivers, canals, marshes, wetlands, or mangroves, the Florida Everglades will provide you with a lifetime of unforgettable experiences.

For freshwater fishing, you will need a Florida freshwater fishing license. Also, fishing is not allowed at the Royal Palm Visitor Center area and trails, Ernest F. Coe Visitor Center lakes, Chekika Lake, along the first 3 miles of the Main Park Road, and along the Shark Valley Tram Road.

For saltwater fishing, you will need to obtain a Florida saltwater fishing license. Fishing is not allowed in Mrazek, Coot Bay, and Eco ponds, at any time, or at the Flamingo Marina before nighttime.

Make sure to check what baits you can use, and what else you need to know before going on your fishing trip.

Anhinga Trail, Everglades National Park, Florida

Hiking in Everglades National Park

Always carry the 10 essentials for outdoor survival when exploring.

There are 29 wonderful hiking, biking, and jogging trails in Everglades. 26 of these routes can be enjoyed by the whole family.

Anhinga Trail

This is a regularly used loop trail near Homestead, Florida that features magnificent wildflowers and is suitable for hikers of all abilities. The route is open all year and is generally utilized for hiking, walking, and bird viewing.

This is the place to go if you want to safely see alligators, turtles, and a variety of bird species from a boardwalk or concrete walkway.

This route is a popular choice for all tourists, especially families with children, because of its short distance and well-maintained paths.

It may become quite hot here in the summer, and there is little to no shade. Bring a lot of sunblock and water with you.

Gumbo Limbo Trail

Gumbo Limbo Route is a short, moderately busy loop trail with a lake that is suitable for all ability levels. Walking, nature visits, and bird viewing are all popular activities on the route.

It is a short and pleasant paved walkway that leads through a gorgeous tropical jungle. This walk is self-guided and runs through a lovely woodland with great native flora and animals. The Gumbo Limbo trees that may be found along the path gave the trail its name.

Mahogany Hammock Trail

Mahogany Hammock Trail is a highly frequented loop trail that features magnificent wildflowers and is suitable for hikers of all abilities. The route is open all year and is generally utilized for walking, nature visits, and bird viewing.

Explore this self-guided boardwalk route that winds through a hardwood "hammock" with a diverse plant community. Gumbo-Limbo trees, as well as air plants and big mahogany trees, abound in this area.

The largest live mahogany tree in the United States may be seen on this wheelchair-accessible route.

How to beat the crowds in Everglades National Park?

While the park is the busiest during the winter, because of its dry season, if you want to avoid the crowd you should choose fall or spring for your visit. Wildlife diversity changes over the seasons, but late fall and early spring still have the features you are hoping for, but fewer visitors.

However, while the dry season is busy, if you book private tours it will feel more deserted. When you have your own naturalist on the boat, you may find some hidden gems in the park and enjoy it even though there are hundreds of other people nearby. The trick is to find tourists you are really interested in and book them in advance.

Where to stay when visiting Everglades National Park

Other than camping facilities, and Flamingo Lodge, Everglades has no other overnight accommodation offered. Miami, Everglades City, Homestead, Florida City, and Chokoloskee are among the cities near the park where many visitors choose to stay.

Flamingo Lodge

Flamingo Lodge has 24 rooms and a new outdoor restaurant opening soon. When booking you can choose from one-bedroom and two-bedroom suites, or a studio.

Every room has a kitchenette and a balcony with a gorgeous view of Florida Bay. You can have your breakfast, lunch, and dinner inside the restaurant that is in the park of the hotel.

The great advantage of staying here is that all the tourists can be booked there, and it has wilderness on your doorstep.

Lodging near Everglades NP

Holiday Inn Express & Suites Florida City - At Holiday Inn Express & Suites Florida City, an IHG Hotel, you can look forward to free continental breakfast, dry cleaning/laundry services, and a gym. Free WiFi in public areas and a business center are available to all guests.

Fairfield Inn & Suites by Marriott Homestead Florida City - Consider a stay at Fairfield Inn & Suites by Marriott Homestead Florida City and take advantage of free full breakfast, a grocery/convenience store, and dry cleaning/laundry services. Free in-room Wi-Fi is available to all guests, along with a gym and a 24-hour business center.

Breezy Palms Resort - At Breezy Palms Resort, hit the beach, relax by an outdoor pool, or spend the day at a marina. Each apartment features a kitchen with a refrigerator and a microwave, plus free Wi-Fi and a TV with cable channels. Other amenities that guests will find include a sitting area and a coffee/tea maker. Weekly housekeeping is available.

Islander Resort - Consider a stay at Islander Resort and take advantage of a poolside bar, a terrace, and a garden. This hotel is a great place to bask in the sun with a private beach, beachfront dining, and beach cabanas. For some rest and relaxation, visit the hot tub. The onsite restaurant, Tides Beachside Bar & Grill, features ocean views and al fresco dining. Enjoy onsite activities like basketball, volleyball, and fishing. Stay connected with free in-room Wi-Fi, with speed of 250+ Mbps (good for 3–5 people or up to 10 devices), and guests can find other amenities such as dry cleaning/laundry services and a bar.

Click on the map below to see the current rates for hotels and vacation rentals near Everglades NP.

Everglades National Park Camping

Camping is a year-round activity in Florida, and inside Everglades National Park, there are two options: Flamingo and Long Pine Key campsites.

Backcountry camping and dispersed camping are also available in the area, but because of all the wildlife you have to prepare very well and follow the “leave no trace” rules.

For a fun adventure check out Escape Campervans. These campervans have built in beds, kitchen area with refrigerators, and more. You can have them fully set up with kitchen supplies, bedding, and other fun extras. They are painted with epic designs you can't miss!

Escape Campervans has offices in Vancouver, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Denver, Chicago, New York, and Orlando

Long Pine Key Campground

This beautiful place is hidden among the long pines, providing a tranquil and private atmosphere. Even though there are 108 campsites here, it will not seem as crowded as Flamingo Campground.

This campground is easily accessible, as it is located just off the highway and has level, paved roads. The Long Pine Key Nature Trail is a short walk away, and there are other fishing ponds in the neighborhood. It's also only a few kilometers from the well-known Anhinga Trail.

If you want to be out in nature, this is the ideal spot to stay. RVs can be reserved ahead of time, but tent camping is on a first-come, first-served basis, so get there early if you want the best places.

The park is open from November to May, and it has potable water, flush toilets, and showers. Phone service and dump stations are also available.

Flamingo Campground

With 234 drive-in campsites and 64 walk-in sites, Flamingo is the most popular and largest campground in the Everglades. It's on the very southwest extremity of the peninsula, 38 miles from the park entrance, and it is open year-round.

Flamingo Campground's position makes it excellent for sailing along the 99-mile wilderness canal, seeing Ten Thousand Islands, and observing wildlife, such as birds, manatees, and dolphins.

All sorts of campers are welcome at Flamingo Campground. Walk-in tent camping, RV spots for rigs up to 45 feet long, houseboat rentals, eco-tents, and cottages are all available.

Flamingo Campground is the place to go if you're searching for a location to stay that's near to nature yet offers a lot of facilities.

There are power connections, a dump station, and hot showers, as well as a fully supplied Marina shop, a food court, and a variety of activity rentals. You may rent a pontoon boat, bicycle, or kayak. Every weekend, there are also daily narrated boat cruises.

Campgrounds near Everglades NP

Goldcoaster RV Resort - Homestead, FL

This campground offers RV Sites, a pool, shuffleboard, internet, laundry, and an arcade.

Sun Outdoors Key Largo - Key Largo, FL

This campground offers lodging and RV sites, beach access, kayaking, a boat launch

Key Largo Kampground - Key Large

This campground offers RV and Tent Sites, a beach, pool, boat launch, and a playground.

Check out additional campgrounds in the area on Campspot

Everglades Facts and Statistics

Elevation: 0 to 8 feet (2.4 m) (average 6 feet / 1.8 m)

Average rainfall: 60 inches (152 cm) per year; Rainy season: May through September (mosquito season coincides with the rainy season)

Hurricane Season: May 1 through November 15

Average temperature: Winter - High 77°F (25 C), Low 53°F (12 C); Summer - High 87°F (31 C), Low 67°F (19 C)

Everglades NP is the largest continuous stand of sawgrass prairie in North America.

Home of thirteen endangered and ten threatened species.

Only subtropical preserve on the North American continent.

"There are no other Everglades in the world. They are, they have always been, one of the unique regions of the earth, remote, never wholly known. Nothing anywhere else is like them; their vast glittering openness, wider than the enormous visible round of the horizon, the racing free saltness and sweetness of their massive winds, under the dazzling blue heights of space. They are unique also in the simplicity, the diversity, the related harmony of the forms of life they enclose. The miracle of the light pours over the green and brown expanse of saw grass and of water, shining and slow-moving below, the grass and water that is the meaning and the central fact of the Everglades of Florida. It is a river of grass."

-Marjory Stoneman Douglas, The Everglades: River of Grass, 1947

Parks near Everglades National Park

Timucuan Ecological and Historical Preserve

Castillo De San Marcos National Monument

Fort Matanzas National Monument

Check out all of the National Parks in Florida along with neighboring National Parks in Alabama and Georgia National Parks

National Park Service Website