Isle Royale National Park may require more planning, but once you learn more about this incredible island, you’ll likely be planning your trip. Below you’ll find the ultimate guide to Isle Royale National Park, including how to get there, when to visit, the park’s history, the best things to do, and more.

Ranger III parked in Rock Harbor

Isle Royale National Park

Isolated by the chilly waters of the largest freshwater lake on earth is a richly forested island of volcanic rock that we call Isle Royale National Park.

It is a world apart, a uniquely secluded northern wilderness where the ruthless delicacy of nature's balance is an observable fact.

This 45-mile-long refuge, some 15 to 18 miles from Canada and about 50 miles from the Michigan mainland, is one of the few places in the lower 48 states where wolves run free and unchallenged.

Playing as they once did across much of the Northern Hemisphere, a vital role in maintaining the health and strength of the wildlife community they prey upon.

About Isle Royale National Park

Isle Royale National Park is located in the northwest region of Lake Superior. While the park technically belongs to Michigan, its location makes it easily accessible from Canada and Minnesota, in addition to the state’s Upper Peninsula.

The park’s remote island location does make it a bit difficult to access, and visitors will need to take either a boat or seaplane out to the island.

In addition, the park is only open for part of the year due to extreme weather (mid-April through late October).

The park is a prime example of undeveloped north woods wilderness and offers very little in the way of modern conveniences.

This is a national park for true adventurers - keep reading to find out more!

Is Isle Royale National Park worth visiting?

Isle Royale is the least visited national park in the lower 48, but that doesn’t mean that you should count it out.

Although the park’s remote location deters most, it is absolutely worth making the trek.

Of all the national parks in the system, Isle Royale has the most repeat visitors. Those who have been to the park know that this hidden gem is worth exploring again and again.

If you decide to make the journey out to Isle Royale, you will be rewarded with unspoiled wilderness, epic hiking trails, hundreds of lakes to fish from, and a gorgeous shoreline that can be explored by canoe or kayak - all without the crowds!

History of Isle Royale National Park

Although Isle Royale has been a protected area for nearly a century, its history goes even further back.

Native Americans used the island for fishing and hunting, and there is evidence of copper pits used to create tools and weapons from this time period as well.

Once Europeans came to the island in the early 1800s, copper mining and commercial fishing were widespread, but are no longer present today.

In 1931 the island and submerged land surrounding it became a national park, and in 1981 Isle Royale became an international Biosphere Reserve.

Even with the presence of mining and commercial fishing operations, the island has remained mostly untouched by the outside world and is one of the best examples of primitive America.

Things to know before your visit to Isle Royale National Park

Isle Royale National Park Entrance Fee

Park entrance fees are separate from camping and lodging fees.

Per-Person Entrance Pass - $7.00 Visitors 16 years or older who enter on foot, bicycle, or as part of an organized group not involved in a commercial tour.

Annual Park Entrance Pass - $60.00, Admits pass holder and all passengers in a non-commercial vehicle. Valid for one year from the month of purchase.

Learn more about National Park Passes for parks that have an entrance fee.

$80.00 - For the America the Beautiful/National Park Pass. The pass covers entrance fees to all US National Park Sites and over 2,000 Federal Recreation Fee Sites for an entire year and covers everyone in the car for per-vehicle sites and up to 4 adults for per-person sites.

Buy your pass at this link, and REI will donate 10% of pass proceeds to the National Forest Foundation, National Park Foundation, and the U.S. Endowment for Forestry & Communities.

National Park Free Entrance Days -Mark your calendars with the five free entrance days the National Park Service offers annually.

Time Zone

Eastern Time

Transportation providers travel on the time zone where their home port is. Make sure to confirm the correct time.

Pets

Pets are NOT allowed on the island including no pets on boats within the park boundaries.

Cell Service

Cell service is not available within the park.

Park Hours

Isle Royale National Park is open every year from April 16 through October 31.

Wi-Fi

Overnight guests at the Rock Harbor Lodge have access to Wi-Fi.

There is no other Wi-Fi available on the island.

There is Wi-Fi available at the Houghton Visitor Center.

Parking

Cars are not allowed on Isle Royale, so there is no need to worry about parking!

Parking is available at the ferry terminals, though you may be required to pay a small daily fee.

Food/Restaurants

There are 2 restaurants at the Rock Harbor Lodge, the Light House Restaurant and Greenstone Grill

Gas

There is no gas available within the park.

Drones

Drones are not permitted within National Park Sites.

Electric Vehicle Charging

There are 33 EV Charging Stations in Houghton, Michigan.

Don't forget to pack

Don't forget to pack

Insect repellent is always a great idea outdoors, especially around any body of water.

We use Permethrin Spray on our clothes before our park trips. Please read my article on preventing biting insects while enjoying the outdoors.

Sunscreen - I buy environmentally friendly sunscreen whenever possible because you inevitably pull it out at the beach.

Bring your water bottle and plenty of water with you. Plastic water bottles are not sold in the park.

Sunglasses - I always bring sunglasses with me. I personally love Goodr sunglasses because they are lightweight, durable, and have awesome National Park Designs from several National Parks like Joshua Tree, Yellowstone, Hawaii Volcanoes, Acadia, Denali, and more!

Click here to get your National Parks Edition of Goodr Sunglasses!

Binoculars/Spotting Scope - These will help spot birds and wildlife and make them easier to identify. We tend to see waterfowl in the distance, and they are always just a bit too far to identify them without binoculars.

Sargent Lake in the wilderness of Isle Royale National Park

Details about Isle Royale National Park

Size - 571,790 acres

The main island of Isle Royale is 50 miles long and 9 miles wide. There are over 400 islands in the park.

Isle Royale NP is currently ranked at 18 out of 63 National Parks by Size.

Date Established

April 3, 1940 - The park was established by President Herbert Hoover.

Visitation

In 2021, Isle Royale NP had 25,844 park visitors.

In 2020, Isle Royale NP had 6,493 park visitors.

In 2019, Isle Royale NP had 26,410 park visitors.

Learn more about the most visited and least visited National Parks in the US

National Park Address

Park Headquarters

800 East Lakeshore Drive

Houghton, MI 49931

Isle Royale National Park Map

For a more detailed map, we like the National Geographic Trails Illustrated Maps on Amazon

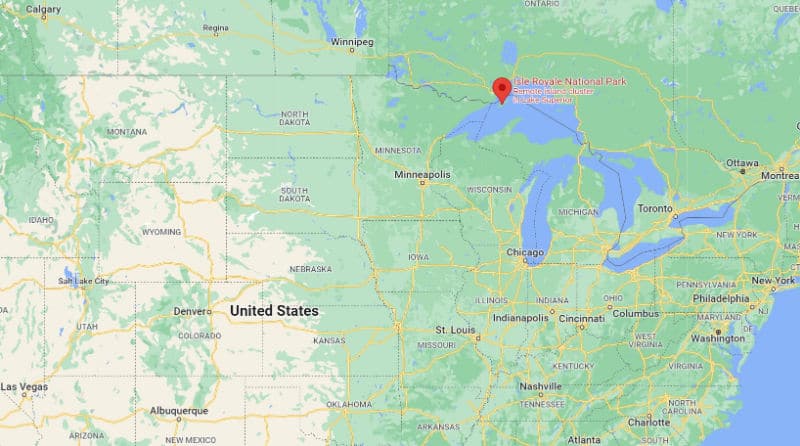

Where is Isle Royale National Park?

Isle Royale is located on an island in Lake Superior in northern Michigan near the border with Canada.

Estimated distance from major cities nearby

Mileage is calculated from the visitor center in Houghton, Michigan.

Minneapolis, MN - 368 miles

Madison, WI - 326 miles

Milwaukee, WI - 326 miles

Chicago, IL - 415 miles

Detroit, MI - 553 miles

Toledo, OH - 591 miles

Estimated Distance from nearby National Park

Voyageurs National Park - 358 miles

Indiana Dunes National Park - 449 miles

Gateway Arch National Park - 676 miles

Cuyahoga Valley National Park - 710 miles

Mammoth Cave National Park - 807 miles

Where is the National Park Visitor Center?

Hougton Visitor Center

Address - 800 E. Lakeshore Drive, Houghton, MI 49931

Rock Harbor Visitor Center

Address - Northeast end of the park.

Windigo Visitor Center

Address - Southwest end of the park.

Credit - NPS/James Strzelinski

Getting to Isle Royale National Park

Closest Airports

Houghton County Memorial Airport (CMX)

International Airports

Austin Straubel International Airport (GRB)

Duluth International Airport (DLH)

Minneapolis St Paul International Airport (MSP)

Regional Airports

Sawyer International Airport (MQT)

Ford Airport (IMT)

Driving Directions

It’s impossible to drive to the park, but there are a few hubs of transportation you can depart from.

Ferries leave from Houghton (southern Keweenaw Peninsula), Cooper Harbor (northern tip of Keweenaw Peninsula), and Grand Portage (northern MN).

Seaplanes depart from Hancock (southern Keweenaw Peninsula) and Grand Marais (northern MN).

Ferry

The ferry is the most common mode of transportation for getting to the park.

Ferry rides can take between three and six hours, depending on where you are departing from.

Ferry times vary, and if you miss your return trip, you’ll be left stranded on the island until the next departure.

Ferry reservations are required.

From Houghton: Ranger III Ferry

From Cooper Harbor: Isle Royal Queen IV

From Grand Portage (MN): Voyageur II & Seahunter III

Seaplane

Royal Air Service from Hancock or Grand Marais (MN) to Windigo or Rock Harbor

Taking a seaplane is certainly the fastest way to reach Isle Royale, but it is also the most expensive. However, the bird’s eye view is worth every penny if you can swing it. Seaplane reservations are required.

Private Boat

Feel free to taxi yourself out to Isle Royale if you have your own boat.

However, note that Lake Michigan is notorious for its unpredictable weather and its rocky bottom and coastline, so proceed with caution!

Best time to visit Isle Royale National Park

Isle Royale is the only park in the entire system that closes down completely for part of the year, so you’ll need to plan your trip between mid-April and late October.

Of course, the weather is at its best in the summer months, and you’ll never have to worry about crowds, but the shoulder seasons have their own appeal as well.

Weather and Seasons

Spring

The park is closed until mid-April, but once the snow begins to melt, the park begins to come alive again with wildlife and visitors.

One of the perks of visiting in the spring is that there are very few visitors on the island, and you’ll also beat the annual mosquito and black fly hatching that occurs in late May.

However, note that the weather may still be a bit iffy in Spring, so check the weather forecast before making any solid plans.

Summer

Your best shot for warm sunny days in the summer, though even these months can be chilly, windy, and stormy.

July is typically the warmest month at the park, though temps rarely reach above 75 degrees Fahrenheit.

Plan for chilly weather and wear plenty of layers as you won’t have much reprieve from the elements on this remote island.

If you visit in the summer, you should also pack plenty of bug spray to ward off the mosquitos and black flies that hatch in late May.

Autumn/Fall

Autumn can be a great time of year to visit the park, especially when the fall foliage is at its peak.

However, temperatures are quite chilly during this time of the year, so plan accordingly. Visitors should also note that the park closes completely on November 1st each year.

Winter

Isle Royale National Park is completely shut-down in the winter (November 1st to April 15th).

Best Things to do in Isle Royale National Park

Wildlife viewing

Wildlife viewing at Isle Royale National Park is unlike any other place on earth. About 99% of the land area is designated wilderness, which means that it has been protected from outside influence.

The most common wildlife sightings at the park include red fox, loons, moose, snowshoe hare, beaver, mink, marten, red squirrel, and river otter.

In the late 1940s, temperatures dropped so low that an ice bridge formed between Isle Royale and Canda, allowing a small pack of Eastern timber wolves to make the crossing.

Their numbers are extremely low, and you probably won’t see any during your visit, but their existence in the park is pretty incredible and worth noting.

Junior Ranger Program

If you brought the kids along on your trip to Isle Royale National Park, be sure to sign them up for the junior ranger program.

This hands-on program will allow your young ones to learn all about the park in a fun way, and once they complete the program, they will receive a cool badge to commemorate their time here.

Fishing

Fishing has long since been a part of the island, and Native American tribes once fished from these very waters.

There are over 100 inland lakes across the island, and you can fish from these permit-free.

Common catches include walleye, trout, northern pike, and perch. If you want to cast out on the big lake (Lake Superior), you’ll need to obtain a Michigan fishing license before arriving at the park.

Paddling

Paddling is a great way to see some of the hidden nooks and crannies of the park.

The most popular area for paddling is around Rock Harbor, and you can rent kayaks and canoes from the Rock Harbor campground or Rock Harbor Lodge. You could also bring your own water vessel along on the ferry for an additional charge.

Guided Boat Tours

If you want to make sure you stay dry while exploring the park, you can book a sightseeing tour with the MV Sandy.

Park rangers lead various different tours around the shoreline with opportunities to disembark and participate in guided hikes.

Tours are available between early June and early September.

Hiking in Isle Royale National Park

Always carry the 10 essentials for outdoor survival when exploring.

There are over 165 miles of hiking trails on Isle Royale, and since there are no roads, this is one of the main ways to get around.

Trails range in length and difficulty, so hikers of all skill levels are sure to find a suitable route or two. We’ve highlighted some of the best of the best below.

Greenstone Ridge Trail - Hard - 43 miles - Point to Point

Named for the 800 feet thick green-hued basalt rock for which it sits, the Greenstone Ridge Trail is a must-hike while at Isle Royale National Park.

Even if you just do a section of the trail, you’ll be treated to incredible views across Lake Superior and the islands surrounding the park.

The best part about this lengthy trail is that it traverses nearly the entire length of the island, so no matter where you are in the park, it's relatively easy to hop on and hike a section.

Mount Franklin via Tobin Harbor Trail - Moderate - 9.4 miles - Out & Back

This popular route follows Tobin Bay along the rocky coastlines. The views are epic, and it’s not uncommon to spot moose and other wildlife along the trail near the pond!

Scoville Point via Stoll Trail - Easy - 4.7 miles - Loop

This is one of the easiest trails at the park, so if you want stunning lake views without all the work, this is one of the best options.

Minong Ridge Overlook - Moderate - 6.6 miles - Out & Back

Don't miss the Minong Ridge Overlook if you’re on the west side of the island (Windigo area). This is a moderately difficult route that ends at the scenic Minong Ridge Overlook.

Hikers will be rewarded with panoramic views of the island’s west end and Lake Superior. On clear days you can even see Canada’s shoreline in the distance.

How to beat the crowds in Isle Royale National Park?

It’s easy to beat the crowds at Isle Royale National Park, mainly because there are none!

This is the least visited national park outside of Alaska, so seekers of solitude need not worry about sharing this rugged expanse with tons of other visitors.

Where to stay when visiting Isle Royale National Park

Rock Harbor Lodge

If you prefer the security of knowing where you’ll rest your head at night, book a room at the Rock Harbor Lodge, located on the northwest side of Isle Royale.

The rooms are a bit dated, but if you want a real bed and a great meal waiting for you after a long day of hiking or paddling, the Rock Harbor Lodge will do splendidly.

Windigo Camper Cabins

There are also two cabins available for rent on the southwest side of the island.

These rustic, one-room cabins are a great retreat from the elements, though they do get booked up extremely quickly each year. So, be ready to book in January for the coming season if you want to snag one of these abodes.

Lodging near Isle Royale NP

The majority of lodging is located in Houghton, Michigan. There is a park visitor center in Houghton along with boat tours that leave to take visitors to the park.

The Vault Hotel - At The Vault Hotel, you can look forward to free to-go breakfast, a fireplace in the lobby, and a 24-hour business center. Guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi.

Quality Inn & Suites - look forward to free continental breakfast, a gym, and a business center at Quality Inn & Suites. For some rest and relaxation, visit the sauna or the hot tub. Stay connected with free in-room Wi-Fi.

Holiday Inn Express Houghton-Keweenaw - Take advantage of a free breakfast buffet, dry cleaning/laundry services, and a fireplace in the lobby at Holiday Inn Express Houghton-Keweenaw, an IHG Hotel. For some rest and relaxation, visit the sauna or the hot tub. The onsite restaurant, Culvers, features American cuisine. Stay connected with free in-room Wi-Fi, and guests can find other amenities such as a gym and a 24-hour business center.

Hampton Inn & Suites Houghton - A grocery/convenience store, a firepit, and laundry facilities are just a few of the amenities provided at Hampton Inn & Suites Houghton. For some rest and relaxation, visit the hot tub. Free in-room Wi-Fi and a gym are available to all guests.

Country Inn & Suites by Radisson, Houghton - look forward to a library, laundry facilities, and a fireplace in the lobby at Country Inn & Suites by Radisson, Houghton, MI. For some rest and relaxation, visit the hot tub. In addition to a gym and a business center, guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi.

Click on the map below to see additional hotels and vacation rentals.

Isle Royale National Park Camping

While there are dozens of different campgrounds to choose from at Isle Royale National Park, there are only a few sites in each campground.

There are also strict limits on how many nights you can stay during the peak season between Memorial Day and Labor Day, some of which are limited to one or two days.

If you are staying for more than a few nights, you’ll likely need to move around a few times. Campers should also note that reservations are not available and all sites are first-come-first-served.

All park campgrounds have outhouses and water sources (non-potable), though visitors will need to pack out all garbage.

Fires are not permitted at most campsites, so plan your meals accordingly. Both visitor centers have showers and laundry services available seasonally.

Below we’ve listed some of the most popular campgrounds, but there are many great options to choose from.

Washington Creek Campground - 5 individual sites - 10 shelters - 4 group sites

Daisy Farm Campground - 6 individual sites - 16 shelters - 3 group sites

Rock Harbor Campground - 11 individual sites - 9 shelters - 3 group sites

Three Mile Campground - 4 individual sites - 8 shelters - 3 group sites

There are also backcountry campsites available - stop in at one of the visitor centers for more info and a permit.

Isle Royale NP Facts

The highest point in the park is Mount Desor at 1,334 feet.

The lowest elevation found in Isle Royale is 601 feet at Lake Superior

Isle Royale National Park is located on Lake Superior, which is the largest freshwater lake in the world.

Parks Near Isle Royale National Park

Grand Portage National Monument

Apostle Islands National Lakeshore

Keweenaw National Historical Park

Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore

Saint Croix National Scenic River

Check out all of the National Parks in Michigan along with neighboring National Parks in Illinois, National Parks in Indiana, Minnesota National Parks, Ohio National Parks, and National Parks in Wisconsin