Complete Guide to Voyageurs National Park including things to do, history, camping, and so much more.

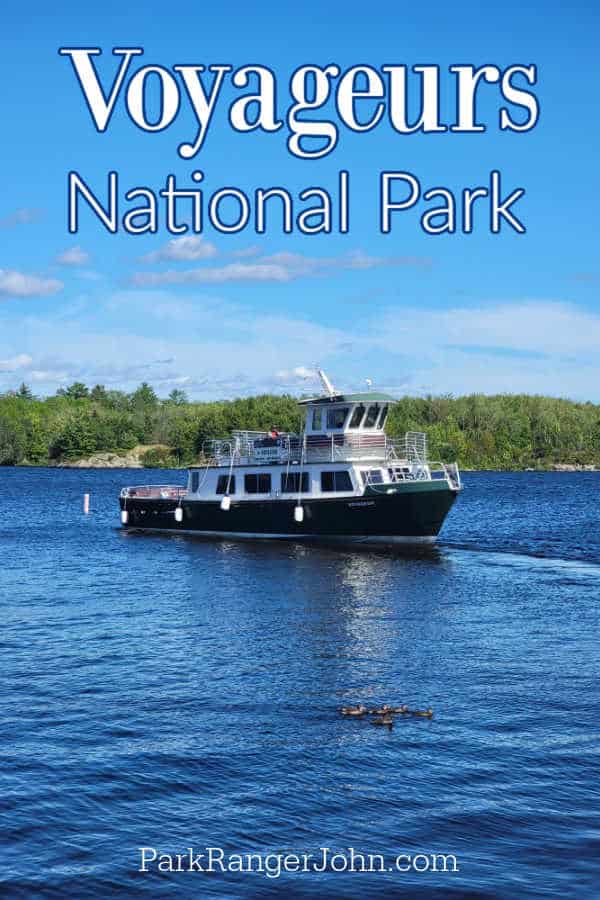

Voyageurs National Park

[mv_video doNotAutoplayNorOptimizePlacement="false" doNotOptimizePlacement="false" jsonLd="true" key="bx6k9cb10y3bjfm7m2nt" ratio="16:9" thumbnail="https://mediavine-res.cloudinary.com/video/upload/bx6k9cb10y3bjfm7m2nt.jpg" title="Little American Island Boat Tour – Voyageurs National Park" volume="70"]

About Voyageurs National Park

Situated way up north near the border between Minnesota and Canada, Voyageurs National Park is home to dozens of lakes and vast expanses of untouched wilderness.

About 40% of the park is comprised of water, making it a paradise for paddlers and lake lovers alike.

You’ll need some type of watercraft to get from point A to point B and everywhere in between, and there are plenty of outfitters in the nearby area to supply you with kayaks, canoes, fishing boats, and more.

Many of the most popular pastimes at voyageurs center around the lakes, including fishing and paddling. Other popular activities here include hiking, wildlife watching, and camping.

Is Voyageurs National Park worth visiting?

Voyageurs National Park is absolutely worth visiting - though it will take a bit more effort and planning than many of the other parks in the system.

You’ll need to bring your own boat or rent one to get around, and the park’s remote location is also a deterrent to some.

Those who do make their way this far up north will be rewarded with complete solitude and one of the most beautiful natural expanses in the world.

Check out our Voyageurs NP Trip Report to see all of the places we stayed, boat tours, restaurants, and so much more.

History of Voyageurs National Park

The park got its name from the French voyageurs (travelers) who meandered these waterways in the 1700s, trading furs and other goods with the Ojibwe Tribe, who dominated the area during this time.

Things to know before your visit to Voyageurs National Park

Entrance fee

$0.00 - There is no entrance fee to visit the park.

Learn more about National Park Passes for parks that have an entrance fee.

Free Entrance Days -Mark your calendars with the five free entrance days the National Park Service offers annually.

Time Zone

Central Time Zone

Pets

Pets must be on a leash less than 6 feet in length.

Pets are only allowed in front country campsites. They are not allowed at back country sites located within the Kabetogama Peninsula.

Pets are allowed on the 1.7 mile recreational trail that follows County Road 96 from Highway 11 to the Rainy Lake Visitor Center.

Pets are allowed in the area surrounding the visitor centers and parking lots.

Cell Service

Cell Service is hit or miss throughout the park.

Park Hours

Voyageurs is open 24-hours a day year-round, although activities and services have seasonal times.

Wi-Fi

Public Wi-Fi is currently available only at the Ash River Visitor Center.

Insect Repellent

Insect repellent is always a great idea when outdoors, especially if you are around any body of water.

We use Permethrin Spray on our clothes before our park trips.

Water Bottle

Make sure to bring your own water bottle and plenty of water with you. Plastic water bottles are not sold in the park.

Food/Restaurants

The only restaurant within the park is at the Kettle Falls Hotel.

Kettle Falls Hotel restaurant is open for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Grocery stores are located in Orr and International Falls, Minnesota.

Gas

There are no gas stations within the park.

Drones

Drones are not permitted within National Park Sites.

National Park Passport Stamps

National Park Passport stamps can be found in the visitor center.

Make sure to bring your National Park Passport Book with you or we like to pack these circle stickers so we don't have to bring our entire book with us.

Voyageurs NP is featured in the 2003 Passport Stamp Set.

Electric Vehicle Charging

The closest EV charging stations are in Virginia, Cook, and Ely, Minnesota.

Details about Voyageurs National Park

Size - 218,222 acres

Voyageurs NP is currently ranked at 32 out of 63 National Parks by Size.

Date Established

April 8, 1975

Visitation

In 2021, Voyageurs NP had 243,042 park visitors.

In 2020, Voyageurs NP had 263,091 park visitors.

In 2019, Voyageurs NP had 232,974 park visitors.

Learn more about the most visited and least visited National Parks in the US

National Park Address

Voyageurs National Park Headquarters

360 Hwy 11 East

International Falls, MN 56649

Voyageurs National Park Map

For a more detailed map we like the National Geographic Trails Illustrated Maps available on Amazon.

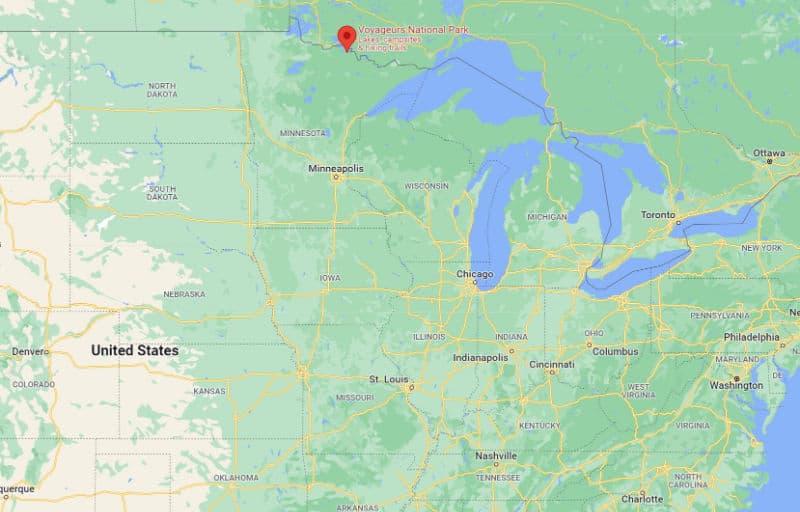

Where is Voyageurs National Park?

Voyageurs NP is located in northern Minnesota near the border with Canada.

Estimated distance from major cities nearby

Distances calculated from International Falls, Minnesota

Winnipeg, Canada - 241 miles

Minneapolis, MN - 276 miles

Saint Paul, MN - 274 miles

Madison, WI - 472 miles

Milwaukee, WI - 539 miles

Omaha, NE - 650 miles

Chicago, IL - 611 miles

Lincoln, NE - 705 miles

Detroit, MI - 892 miles

Estimated Distance from nearby National Park

Isle Royale National Park - 406 miles

Indiana Dunes National Park - 645 miles

Theodore Roosevelt National Park - 581 miles

Badlands National Park - 695 miles

Gateway Arch National Park - 822 miles

Cuyahoga Valley National Park - 959 miles

Where is the National Park Visitor Center?

Rainey Lake Visitor Center

Location - Shores of Black Bay

Season - Year round

Address - Rainy Lake Visitor Center

1797 Township Rd 342

International Falls, MN 56649

Kabetogama Lake Visitor Center

Location - southwest shoreline of Kabetogama Lake

Season - Late May to late September

Address - 9940 Cedar Ln

Kabetogama, MN 56669

Ash River Visitor Center

Location - in the historic Meadowood Lodge

Season - late May to late September

Address - 9899 Mead Wood Rd

Orr, MN 55771

Getting to Voyageurs National Park

Closest Airports

Falls International Airport (INL)

Fort Frances Municipal Airport (YAG)

International Airports

Duluth International Airport (DLH)

Hector International Airport (FAR)

Minneapolis International Airport (MSP)

Driving Directions

Due to its remote location, most visitors fly into International Falls and drive about 20 minutes to the park boundary via MN 11-E.

Public Transportation

There is no public transportation to Voyageurs NP.

How to get around Voyageurs National Park

Because it is comprised of about 40% water, most of Voyageurs National Park is only accessible by boat. This makes it a bit trickier to get from place to place, but fear not.

There are tons of trusted outfitters, lodges, and guides that rent out different kinds of boats, so all you need to do is decide your preferred method of transportation.

Below you’ll find a list of the most popular ways to get around Voyageurs.

Canoe

Traveling around via canoe is one of the most tried and trusted methods of transport in the park.

Voyageurs of days past used canoes to explore the area, and today it's one of the most popular boats on the lakes.

It’s easy for beginners, and it's also one of the least expensive ways to get around. If you plan on going far in a short amount of time, this may not be the best option, but if you have time and patience this is the purest way to experience the park.

Small Fishing Boats

You’ll likely see quite a few small fishing boats out on the lakes, and this is another great way to explore the park.

This is especially true if you don’t have much boating experience but don’t feel up to paddling your way around.

While models vary, most small vessels available for rent will consist of an aluminum base, a pull-to-start motor, and three or more seats.

Larger Fishing Boats and Pontoons

You could also rent a larger fishing boat or pontoon to get around the park. These usually come equipped with all the bells and whistles, including steering wheels, electric start, and throttles.

There is more room on the bigger boats, along with plenty of comfy seating for more passengers. The only downside is that it may be hard to find spots to dock it when it comes time to get off and explore.

Historic Mining Equipment, Little American Boat Tour, Voyageurs National Park, Minnesota

Best time to visit Voyageurs National Park

Weather will have a huge impact on what kind of experience you have at Voyageurs, so it’s important to know exactly what to expect in each season. Minnesota has four solid seasons, each with its own charm and potential challenges.

Weather and Seasons

Spring

Spring is universally known as a time of renewal, and it’s no exception at Voyageurs National Park. As the snow starts to melt, trees begin to blossom, wildflowers bloom, and temperatures slowly begin to climb. There are also relatively few visitors during the spring, so if you’re looking for some solitude during your time at the park this is a great time to visit.

Summer

Summer is the most popular time of year at the park, as the weather is at its best and the hours of daylight stretch a bit further in these months.

There are also tons of fun activities available at the park during these months, including fishing, hiking, paddling, and more.

Unfortunately, summer also brings massive swaths of mosquitoes, biting flies, and ticks, so bring plenty of insect repellent and other protection against these bad boys.

Fall

Autumn is one of the best times to visit Voyageurs. The summer crowds have trickled out (as have much of the mosquito hoards), and the park’s foliage is ablaze in a fiery color show of vibrant reds, yellows, and oranges.

Timing the peak fall foliage can be a bit tricky, but visiting between late September and early October is your best bet. At night, the color show continues, and you can often see the skies dancing with the northern lights.

Winter

Winter is the longest season in the park, and it brings some of the coldest temperatures in the entire country. Temperatures often plummet well below zero, with a record-breaking low of a frigid -55° Fahrenheit.

Wind chills can make these freezing temps feel even colder, so proper planning for this winter wonderland is an absolute must.

Those who do brave the cold weather will actually find white a lot to do in the park during the colder months, including ice-fishing on the frozen lakes, snowmobiling, cross country skiing, and snowshoeing.

If you don’t own a pair of snowshoes or skis, you can rent some for free from the Rainy Lake Visitor Center.

Best Things to do in Voyageurs National Park

[mv_video doNotAutoplayNorOptimizePlacement="false" doNotOptimizePlacement="false" jsonLd="true" key="bx6k9cb10y3bjfm7m2nt" ratio="16:9" thumbnail="https://mediavine-res.cloudinary.com/video/upload/bx6k9cb10y3bjfm7m2nt.jpg" title="Little American Island Boat Tour – Voyageurs National Park" volume="70"]

Wildlife Watching

Voyageurs National Park is home to a wide variety of wildlife, including black bears, wolves, moose, and bald eagles.

Most of these creatures are quite elusive, with the exception of the bald eagles. Minnesota is home to one of the largest populations of bald eagles in the country, and Voyageurs is one of the best spots for spotting these magnificent birds.

Look towards the treetops to sport their massive nests, or take one of the guided boat tours and let the rangers point them out for you.

Other wildlife you may spot in the park includes deer, otter, beavers, porcupines, hare, fox, loons, and owls, amongst others.

Guided Tours

Throughout the summer and fall seasons, daily guided boat tours are available from the Rainy Lake and Kabetogama visitor centers.

This is a great way to see the park if you’re not keen on paddling or if you’re interested in learning about this region from one of the knowledgeable park rangers. Various tours are available and can be reserved online in advance.

Check out the Little American Island Boat Tour we took during our visit to the park.

Junior Ranger Program

Completing a junior ranger program is a great way to learn more about the park in a fun, hands-on way.

No matter if you’re young or young at heart, the program allows you to slow down and enjoy all the aspects of the park, many of which you might miss if you’re exploring on your own. At the end, you’ll even receive a cool badge to commemorate your time here.

Ellsworth Rock Garden

The Ellsworth Rock Garden is a must-see at Voyageurs National Park. This one-of-a-kind stone “garden” is the work of one man - Jack Ellsworth - over the course of 20 years.

Ellsworth started creating these incredible structures back in the 1940s, and most have stood the test of time.

Some of the most impressive statues are composed of precariously placed rocks balanced on top of one another, creating massive monoliths that look as though they could topple over at any minute.

The rock garden is located on the shores of Lake Kabetogama, and like so much of the park, it can only be reached by boat.

Fishing

Anglers from far and wide make the pilgrimage to Voyageurs National Park each year to cast out in these abundant waters. You can fish anywhere in the park with the exception of Beast Lake - just make sure you have a valid Minnesota fishing license.

There are over 50 species swimming through these waters, including smallmouth bass, northern pike, lake sturgeon, black crappie, and walleye. The walleye fishing here is thought to be some of the best in the country, and some even consider it one of the best fishing spots in the world for this particular species.

Whether you’re fishing for dinner or for sport, there’s something special about casting out in the calm lakes of the park that have visitors coming back time and again.

Beaver Lake Trail, Voyageurs NP, Minnesota

Hiking in Voyageurs National Park

Always carry the 10 essentials for outdoor survival when exploring.

Many of the trails inside Voyageurs National Park can only be reached by boat, but there are a few routes that you can access by vehicle as well. We’ve highlighted some of the most popular treks in the park below.

Ethnobotanical Garden Trail - Easy - .25 miles - Loop

Little American Island Loop Trail - Easy - .25 miles - Loop

Rainy Lake Recreation Trail - Easy - 5 miles - Out & Back

Forest Overlook Trail - Easy - .3 miles - Loop

Kabetogama Lake Overlook Trail - Easy - .4 miles - Out & Back

Echo Bay Trail - Easy - 1.6 miles - Loop

Blind Ash Bay Trail - Moderate - 3 miles - Out & Back

Kab Ash Trail - Moderate - 11.2 miles - Point to Point

How to beat the crowds in Voyageurs National Park?

Having just barely eeked its way out of the ten least visited parks in the nation, it's safe to say that you won’t have to worry about big crowds at Voyageurs National Park.

During the summer months, you’ll likely see other boats on the water and may encounter people at the visitor centers, but other than that, the peace and quiet of this remote oasis is all-encompassing.

[mv_video doNotAutoplayNorOptimizePlacement="false" doNotOptimizePlacement="false" jsonLd="true" key="ixbqdd5meqokbkaws9nt" ratio="16:9" thumbnail="https://mediavine-res.cloudinary.com/video/upload/ixbqdd5meqokbkaws9nt.jpg" title="Kettle Falls Hotel - Voyageurs National Park" volume="70"]

Where to stay when visiting Voyageurs National Park

Kettle Falls Hotel

Situated on the Kabetogama Peninsula, Kettle Falls Hotel is one of the best and most popular lodging options at Voyageurs.

This historic hotel was built in the early 1900s and offers up both rustic villas and standard hotel rooms.

Like most areas of the park, the hotel is only accessible from the water. But even those who don’t have a boat can access Kettle Falls Hotel thanks to their boat shuttle service.

The hotel is open seasonally from May to September, and rooms get booked up extremely quickly, so try to make your reservation well in advance if you hope to snag one of these coveted spots.

Houseboating

Houseboating is another popular form of accommodation at Voyageurs. This type of camping on the water is allowed in designated areas only, and a permit is also required.

There are a limited number of permits available each year, so be ready to make your reservation in November for the upcoming summer season.

Houseboat rentals are available in a number of the gateway communities surrounding the park.

Camping

There are no designated campgrounds inside Voyageurs National Park, though there are about 150 individual sites available to visitors.

Sites are spread far apart (many of which sit on islands in the lakes), ensuring a truly secluded camping experience for each and every overnight guest at the park.

The sites are even considered front country - so you won’t be completely roughing it. That being said, sites are only accessible by water, so you’ll need to find your way to shore from whatever watercraft you have at your disposal.

In addition, reservations are required, and you’ll need to obtain a permit to camp.

Once you make it to your site, you’ll find everything you’ll need waiting for you, including a dock, a fire ring, a designated area for your tent, bear-proof food lockers, and a pit toilet.

Of course, if you are looking for an even more primitive experience, there are 15 backcountry sites available around the park as well. Just be sure to obtain a backcountry permit before seeking these out.

Suppose the idea of being stranded on your own private island for the night doesn’t excite you. In that case, there are drive-in campsites available at the nearby Kabetogama State Forest, situated on the shores of Lake Kabetogama.

Additional Resources

Voyageurs National Park and Paddle Routes (National Geographic Trails Illustrated Map)

Voyageurs National Park Activity Book: Puzzles, Mazes, Games, and More About Voyageurs National Park

Paddling the Boundary Waters and Voyageurs National Park

Parks Near Voyageurs National Park

Grand Portage National Monument

Apostle Islands National Lakeshore

Saint Croix National Scenic River

Effigy Mounds National Monument

Check out all of the National Parks in Minnesota along with neighboring Iowa National Parks, Michigan National Parks, North Dakota National Parks, National Parks in South Dakota, and Wisconsin National Parks