Grassy prairies surround Badlands National Park and is the largest park of its kind in the United States.

Its rocky, eroded pinnacles and buttes suddenly appear on the flat landscape, drawing the imagination of all who stare upon its beauty.

Badlands National Park

Badlands National Park is a park that you just have to see to believe. The wide-open vistas are truly breathtaking.

Badlands NP is located in southwestern South Dakota and was established as a park in 1978.

About Badlands National Park

Badlands National Park is 244,000 acres and was created to protect an expanse of mixed-grass prairie where bison, bighorn sheep, prairie dogs, and black-footed ferrets live.

The Badlands Wilderness Area covers 64,250 acres and helped with the reintroduction of the bison.

The Badlands Loop Road (Hwy 240) is 27-miles long and takes you through the formations of the Badlands from either direction.

We suggest driving the loop in both directions so you can see as much as possible of the park.

Is Badlands National Park worth visiting?

YES! I personally think this is one of the easiest parks to visit. The park is easy to explore through the Badlands Loop Drive with several short hikes and overlooks.

Wildlife can be spotted throughout the park and the park's major highlights can be seen in a day.

History of Badlands National Park

There are badlands throughout the West, where treeless plains are being cut to pieces, shaped and reshaped by erosion.

But jagged Badlands National Park is the biggest and the baddest, from which all other badlands take their name.

The overall Badlands actually covers about 6,000 square miles of South Dakota and Nebraska. Only about 13 percent of this land is contained in the national park.

When the Sioux coined the term mako sica (literally, "bad land"), they probably meant nothing more than to distinguish the austere clay spires and gullies from the surrounding grassy plains.

The Indians most likely found the Badlands to be good hunting grounds. Bison and other wildlife drew hunters here as far back as 10,000 years ago. Badlands cliffs, often invisible when approached from the north and east, made ideal "buffalo jumps," where bison were stampeded to their deaths.

About 500 of the great shaggy beasts can still be seen grazing in the Sage Creek Wilderness Area.

French fur traders called the region mauvaises terres à traverser (literally, and quite accurately, "bad lands to travel across"). For a traveler, it is an apt description of this seemingly barren landscape–slashed and gouged by impossible gullies and ravines–that becomes a giant mud pie when it rains.

Yet only 45 miles west of Badlands National Park are the Black Hills, a delightful island of forested "good lands" that helps the traveler appreciate by contrast the Badlands' hostile grandeur.

Fairly recently, as geologists measure time, the Badlands flowed from these good lands. Beginning about 65 million years ago, when the Rockies began to form, the same pressures raised the land here, draining a shallow sea that had covered the region for 15 million years.

Meanwhile, to the west, the surface warped into a blister, or dome, nearly 8,000 feet high–the Black Hills.

As the dome rose, it was slowly eroded. Streams became torrents, stripping rock from the hills and carrying it east to a broad, level valley where the sea had been.

Here the torrents slowed to meandering streams and dropped the hills' debris. Over millions of years, the valley was filled with sediments up to 1,500 feet thick.

By the beginning of the Oligocene period, about 34 million years ago, the climate of the area resembled that of today's Gulf Coast.

Rivers and streams made mudflats and marshes, then filled them with sediment to create forests and grasslands while beginning new swamps elsewhere.

The sediments were by no means evenly distributed. The erratic routes of streams, the fluctuating rates of precipitation, the variety of debris from different sites in the Black Hills, the masses of volcanic ash that occasionally blew in from the west all contributed to the patchwork layering that gives today's Badlands their distinctive banded appearance.

These layers are, for the most part, mudstone and siltstone: materials so insubstantial that it seems an exaggeration to call them stone at all.

Little sediment has been added over the last million years. Instead, the whole place is falling apart, being carried away in rivulets that feed the White, Bad, and Cheyenne rivers.

It is one of the world's most rapidly dissolving landscapes. In a few million years, the Badlands will very likely be gone.

Geologists speak matter-of-factly of a million years, but we short-lived human beings cannot really comprehend such time spans.

In the Badlands, though, geologic events tear along at rates discernible to human eyes. In 1959 the U.S. Geological Survey set metal discs in concrete embedded atop hills near Dillon Pass.

These were designed to be permanent reference points for mapmakers, but the hills eroded away at the rate of an inch a year. In a little over a decade, the "permanent" benchmarks and their concrete bases were embedded in nothing–which was just as well, for the elevations they recorded were now wrong by a foot.

Much of the clay eroded from the Badlands ends up in the White River, named for the chalky color imparted by its burden of sediment.

This water is foul stuff. Each of the clay particles has the same electrical charge, and so they repel one another. They cannot clump together to settle out of the water. Perhaps the area should be called badwaters instead of badlands.

When the famed mountain man Jedediah Smith and his rugged band were scouring the West for beaver pelts in 1823, they drank from the White River, the only water available.

They suffered severe diarrhea, followed by dehydration that could easily have killed them in such an arid country. Two of the men were too weak to go on.

Smith buried them up to their necks in the sand to conserve body moisture until he could return with drinkable water.

It is a testimony to Smith's character and leadership that his men let themselves be buried alive, trusting that he both could find water and would bring it back. That night he did so and dug them out.

Learn more about the history of Badlands National Park

Things to know before your visit to Badlands National Park

Badlands National Park Entrance Fee

Park entrance fees are separate from camping and lodging fees.

Park Entrance Pass - $30.00 Per private vehicle (valid for 1-7 days from the date of purchase)

Park Entrance Pass - Motorcycle - $25.00 Per motorcycle (valid for 1-7 days from the date of purchase)

Per-Person Entrance Pass - $15.00 Visitors 16 years or older who enter on foot, bicycle, or as part of an organized group not involved in a commercial tour.

Annual Park Entrance Pass - $55.00, Admits pass holder and all passengers in a non-commercial vehicle. Valid for one year from the month of purchase.

$40.00 to $115.00 for commercial sedans with 1-6 seats, $25.00 per vehicle plus $15.00 per person

$50.00 for commercial van with 7-15 seats

$60.00 for commercial mini-bus with 16-25 seats

$150.00 for commercial motorcoach with 26+ seats

Time Zone

Mountain Standard Time (MST)

Pets

Pets are allowed within Badlands NP. Pets must be on a leash no longer than 6 feet long.

Pets are allowed in the park but must be on a leash less than 6 feet in length. Pets are not allowed on trails, backcountry areas, or inside buildings.

If your pet needs more room to walk, consider visiting the trails managed by US Forest Service, Buffalo Gap National Grassland, located adjacent to Badlands National Park, where pets are permitted (with some exceptions).

For more information contact the Buffalo Gap Visitor Center which is located in Wall at (605) 279-2125.

Cell Service

Cell phone coverage for major carriers varies throughout the park from full coverage to no coverage depending on your location in the park.

Park Hours

The park is open to visitors all year with the exception of weather closures.

Wi-Fi

Public WIFI is available at the Ben Reifel Visitor Center.

Parking

There are several parking lots located in Badlands National Park including the visitor center, trailheads, and several scenic overlooks along the Badlands Loop Road.

Food/Restaurants

The Cedar Pass Lodge is the only location within the park where you can purchase food. Here you can buy snacks, get food to go and sit down dining.

They provide a variety of regionally sourced dishes as well as make their own fry bread each day for their Sioux Indian Tacos.

Gas

There is no gas available within the park. There is gas available in Wall, South Dakota.

Don't forget to pack

Insect repellent is always a great idea outdoors, especially around any body of water.

We use Permethrin Spray on our clothes before our park trips. Please read my article on preventing biting insects while enjoying the outdoors.

Sunscreen - I buy environmentally friendly sunscreen whenever possible because you inevitably pull it out at the beach.

Bring your water bottle and plenty of water with you. Plastic water bottles are not sold in the park.

Sunglasses - I always bring sunglasses with me. I personally love Goodr sunglasses because they are lightweight, durable, and have awesome National Park Designs from several National Parks like Joshua Tree, Yellowstone, Hawaii Volcanoes, Acadia, Denali, and more!

Click here to get your National Parks Edition of Goodr Sunglasses!

Binoculars/Spotting Scope - These will help spot birds and wildlife and make them easier to identify. We tend to see waterfowl in the distance, and they are always just a bit too far to identify them without binoculars.

Electric Vehicle Charging

The closest EV Charging station to Badlands is Wall, South Dakota. They are approximately a two-minute walk from Wall Drug.

Details about Badlands National Park

Size - 242,755 acres

Badlands is currently ranked at 28 out of 63 National Parks by Size.

Date Established

Badlands became a National Park on November 10, 1978, by the 39th President of the United States, Jimmy Carter

Visitation

In 2021, Badlands, NP had 1,224,226 park visitors

In 2020, Badlands NP had 916,932 park visitors.

In 2019, Badlands NP had 970,998 park visitors.

Badland National Park Address

25216 Ben Reifel Road

Interior, SD 57750

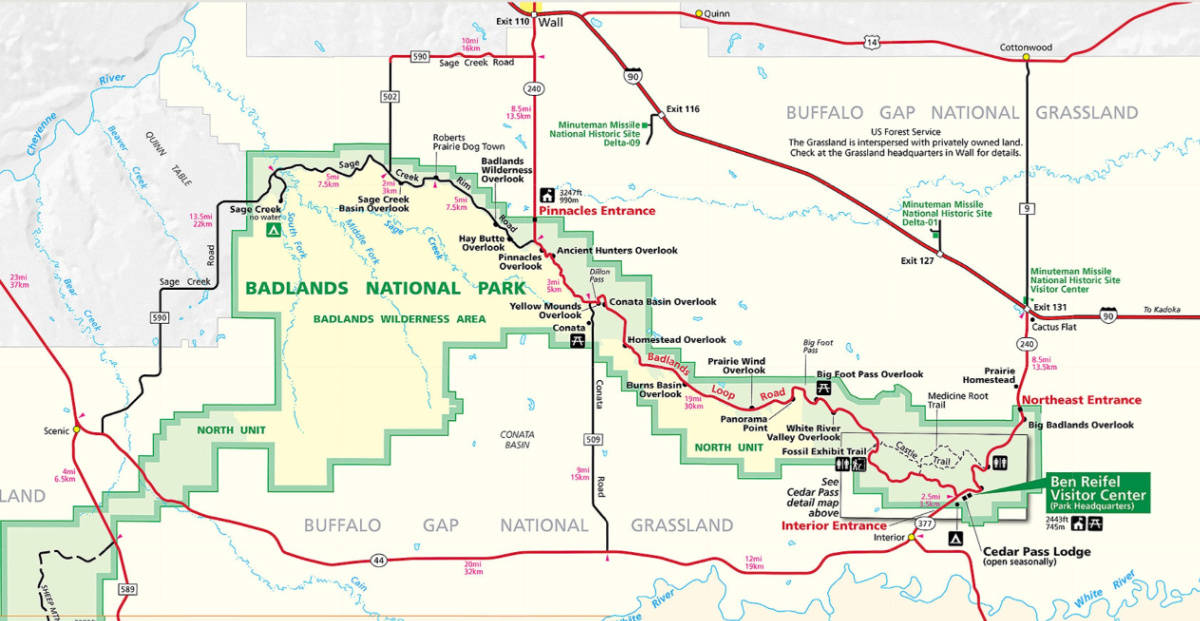

Badland National Park Map

Where is Badlands National Park?

Badlands National Park is located 75 miles east of Rapid City, South Dakota.

The easiest way to get to Badlands NP is off of I-90 at exit 131 (Cactus Flats) or at the Wall exit. Drive south to the park entrance stations from the exit.

Estimated distance from major cities nearby

Wall, SD - 7.5 miles

Rapid City, SD - 76.2 miles

Sturgis, SD - 108 miles

Custer, SD - 83 miles

Deadwood, SD - 100 miles

Denver, CO - 369 miles

Lincoln, NE - 443 miles

Minneapolis, MN - 502 miles

Wichita, KS - 616 miles

Kansas City, MO - 630 miles

Estimated Distance from nearby National Park

Theodore Roosevelt National Park - 323 miles.

Wind Cave National Park - 54 miles

Yellowstone National Park - 555 miles

Glacier National Park - 749 miles

How far is Badlands National Park from Mount Rushmore?

Badlands National Park is located 114 miles or 1.5 - 2 hours from Mount Rushmore National Memorial and only an hour from Rapid City.

Where is the Badlands National Park Visitor Center?

The Ben Reifel Visitor Center is located on the Cedar Pass "Badlands Loop Road" Hwy 240.

The visitor center has a 95-seat air-conditioned theater showing the new film, Land of Stone and Light.

You can also pick up park maps, brochures and ask a ranger any questions you have about the park.

Hours of Operation - Mountain Time Zone

8 a.m. - 4 p.m. (Winter Hours)

8 a.m. - 5 p.m. (April & May)

7 a.m. - 7 p.m. (Summer Hours)

8 a.m. - 5 p.m. (early September to late October)

CLOSED on Thanksgiving, Christmas Day, and New Year's Day

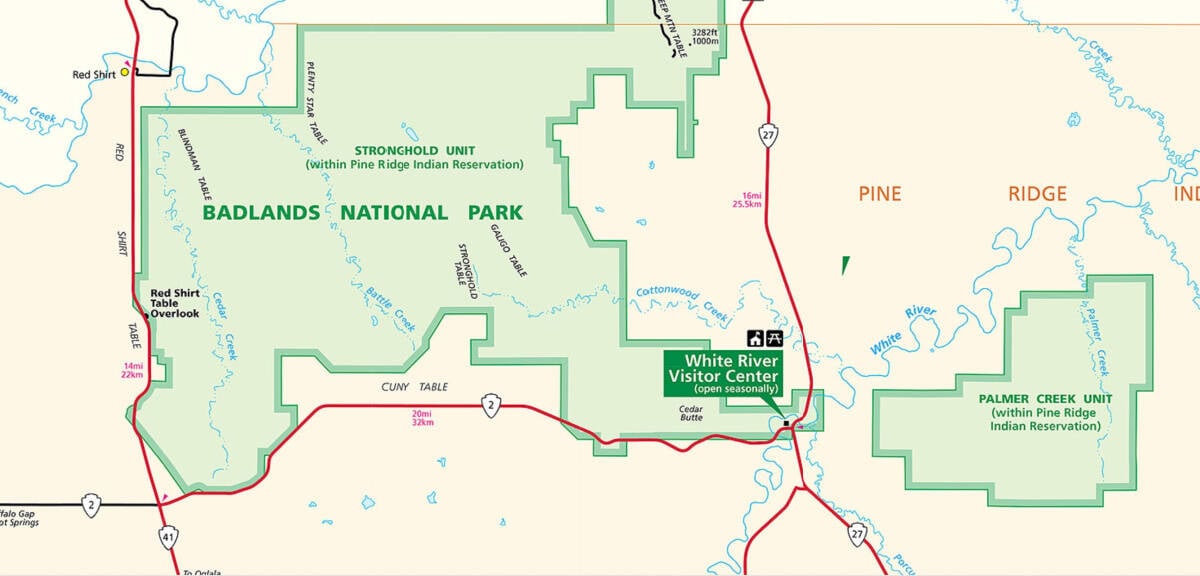

The White River Visitor Center is open seasonally. The White River Visitor Center is located on Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in the South Unit of Badlands NP.

The visitor center has a bookstore, restroom, interpretive exhibits, and park movies.

Getting to Badlands National Park

Closest Airports

Rapid City Regional Airport (RAP): One hour, 15 minutes, 68 miles

International Airports

Minneapolis-St Paul (MSP) 8 Hours, 506 miles

Regional Airports

Driving Directions

The easiest way to get to Badlands NP is off of I-90 at exit 131 (Cactus Flats) or at the Wall exit. Drive south to the park entrance stations from the exit.

Best time to visit Badlands National Park.

I would suggest late summer to early fall would be the best time to visit. This is where you will find smaller crowds, the temperatures starting to cool down and wildlife to be seen throughout the park.

Of course if you can catch the Badlands in late spring after the rains have come you will be treated with beautiful green rolling hills that really make photos pop with color in the Badlands.

Badlands National Park Weather and Seasons

The weather in Badlands NP tends towards the extremes! Extremes range from 116° F to -40° F, with hot and dry summers.

During Summer you can expect temperatures to be over 100 degrees while in the winter it may be below freezing.

Please be prepared with layers of clothes, sunscreen, bug spray, sturdy walking shoes, and lots of water.

Spring

The temperature in the Spring is very pleasant, however, it’s much more common to get heavy rainstorms and even hail.

Late spring also signals western South Dakota’s rainy season, when the area receives over a third of its annual moisture.

Precipitation in May comes mostly in short rain showers and this is typically the wettest month.

March and April are some of the driest months but it's not unheard of to receive snow showers that can dump sizeable amounts.

Summer

The park gets about 16 inches of annual precipitation with June being the wettest month. The park is very hot from July through August and oftentimes exceeds 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

Campgrounds are typically full during August since many motorcyclists are heading to/from Sturgis Motorcycle Rally which draws over half a million visitors each year!

Autumn/Fall

Perhaps the best time to visit Badlands is late August through September, with the couple weeks after labor day, when all the kids are back in school.

This is also a great time to view the park's bounty of wildlife.

Winter

The roads through Badlands often close after extreme weather events. Always check road conditions before taking your trip and drive a vehicle up to driving in inclement weather.

Winters here are typically cold and receive an average of 12-24 inches of snow each year.

Best Things to do in Badlands National Park

Drive the Badlands Loop Road

The easiest way to explore Badlands National Park is by driving the 27-mile long Badlands Loop Road (Hwy240). This scenic road will take you through some of the most colorful rock formations you can imagine with lush green grasslands in between. There are several parking lots to pull into with overlooks and trails to hike.

Watch Sunrise/sunset

Watching sunrise and sunset over the badlands is just breathtaking! The key is to find the right location and to make sure to be there for the golden hour not just the sun setting.

I have found the softer light in the golden hour is magic against the rugged scenery of the Badlands.

Wildlife viewing

Badlands is one of my favorite National Parks for viewing wildlife!

One of my favorite conservation efforts is located in Badlands National Park. Did you know that Bison was native to the Badlands before they were eradicated well before becoming a National Park. Conservation efforts began when 50 bison that were reintroduced to the park in the 1960's , An additional 20 bison was introduced in the 1980's. Today, the parks Bison population has reached approximately 1,200! Visitors have their best chance of seeing Bison on the west side of the park.

The park has much more than Bison, there is a good population of Bighorn Sheep, Pronghorn, deer, prairie dogs and well over 100 different bid species call this area home.

Junior Ranger Program

The Junior Ranger Program can be picked up at the visitor center. This is a great way for visitors of all ages to learn more about the park.

Also, check with the visitor center for the Night Sky Junior Ranger Program.

From June through August the park offers specific Junior Ranger programs and interpretive sessions. Check with the visitor center for current times.

Bird Watching

Badlands National Park is a great birding destination specifically for its grassland species. Currently, there are over 100 species that call the Badlands home.

With the increased concern about climate change and warmer temperatures, we could see declines in grassland birds that breed in the Badlands in the summer such as the Upland Sandpiper, Horned Lark, and Burrowing Owl, and the Mountain Bluebird. Other species that easily adapt to more arid regions will continue to thrive

Guided Tours

There are a couple of really cool guided tours available in Badlands Natl Park.

Badlands NP Private Tour - Enjoy a private tour of the park and stop at famous features including a stop at Wall, South Dakota. Learn about the history of the area and spend the day discovering the rare geology of the Badlands.

Badlands Tour with Minuteman Missile NHS - Travel to Badlands National Park and explore this spectacular terrain on a full-day guided tour. Catch a glimpse of America's nuclear arsenal during the Cold War and learn about its history with your expert guide.

Badlands Bike Tour with Lunch - Join a bike tour of Badlands National Park. Cycle around the park and learn its history from your experienced guide. Admire the spectacular scenery and wildlife as you pedal.

Hiking at Badlands National Park

There are eight developed hiking trails in Badlands National Park including one of my all-time favorite hikes in the National Park System, The Notch Trail!

Don't let that limit your imagination of exploring Badlands because the entire 244,000 acres of the park are open to hikers.

Just make sure to be responsible when exploring beyond the park's designated trails as your safety is your responsibility. This area is remote, rugged, hot, and unforgiving.

You can run into anything from Bison to Rattlesnakes and the Badlands themselves can easily get you disoriented. Always carry the 10 essentials for outdoor survival when exploring the backcountry.

How to beat the crowds in Badlands?

If you want to feel like you are the only person in the park, simply show up in December when park visitation is approximately 8000 visitors for the entire month!

This is a much different contrast to the 288,000 visitors that July receives! That's a difference of 258 visitors a day versus 9290 visitors a day!

Where to stay when visiting Badlands National Park

Whether you want to stay in a lodge, cabin, RV, or tent, you will find everything you need to know below.

Badlands National Park Lodging

Cedar Pass Lodge and Cabins: are located near the Ben Reifel Visitor Center within Badlands National Park. Cedar Pass Lodge offers cabins, a full-service restaurant, and a gift shop. Cedar Pass Lodge is normally open from mid-April through mid-October depending on the weather.

Badlands Inn: Badlands Inn is located just outside the boundary of Badlands National Park. This is the closest hotel to Badlands National Park and only a few minutes away from the park's visitor center.

Lodging near the park includes:

Best Western Plains Motel - Free continental breakfast, an arcade/game room, and a gym are just a few of the amenities provided at Best Western Plains Motel. For some rest and relaxation, visit the hot tub. In addition to a business center, guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi.

Econo Lodge Wall - free to-go breakfast and more. Guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi.

Super 8 by Wyndham Wall - free to-go breakfast and a business center. Guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi.

Americas Best Value Inn Wall - free continental breakfast, a free daily manager's reception, and laundry facilities. Stay connected with free in-room Wi-Fi, and guests can find other amenities such as a bar and a gym.

Days Inn by Wyndham Wall - free to-go breakfast, laundry facilities, and a gym at Days Inn by Wyndham Wall. Free in-room Wi-Fi and conference space are available to all guests.

Click on the map below to see additional vacation rental and lodging options near the park.

Badlands National Park Camping

There are two front country campgrounds in Badlands National Park; Cedar Pass Campground, and Sage Creek Campground.

Cedar Pass is the largest of the two and is located near the park's visitor center and most of the park's most popular attractions.

Sage Creek requires a bit more to get to but the drive is beautiful and we saw lots of Bison, sheep, and prairie dogs!

For a fun adventure check out Escape Campervans. These campervans have built in beds, kitchen area with refrigerators, and more. You can have them fully set up with kitchen supplies, bedding, and other fun extras. They are painted with epic designs you can't miss!

Escape Campervans has offices in Vancouver, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Denver, New York, and Orlando

Readers Tips for Badlands NP

When you see a bathroom use the bathroom!

Hike the Notch Trail early to beat the crowds (and the heat) for a summer visit! ~Amy

Go early in the day. It gets very hot. The visitor center has a map that identifies where you see where animals have been spotted. Leave the main road and take your time. I would not stay in Wall if I had to do it again. We also enjoyed the Minuteman missile visitor center and site nearby. Make reservations early if you want to go into the site. ~Cheryl

Be there at sunrise and/or sunset to see the march of the Bighorn Sheep. ~Tim

Badlands National Park Facts

What is the highest point in the park?

The highest point in the park is 3,247 feet or 1,009 meters, located at the Pinnacles Entrance Station.

How did the park get its name?

Badlands National Park is located in the White River Badlands and was called mako sica (mako, land and sica, bad) by the Sioux Indians. The term badlands generally refers to an area that is difficult to travel through primarily because of the rugged terrain and lack of water. The fascinating landscape within the park erodes at a rate of about 1 inch per year, providing an ever-changing landscape.

How much precipitation does the park receive every year?

The average annual precipitation is 16 inches

Additional Resources

Badlands NP Activity Book: Puzzles, Mazes, Games, and More

Retro Vintage Badlands National Park T-Shirt

Fodor's The Black Hills of South Dakota: with Mount Rushmore and Badlands

Badlands Park: South Dakota, USA Outdoor Recreation Map

Badlands Magnet by Classic Magnets, Discover America Series

Parks near Badlands National Park

Minuteman Missile National Historic Site - Learn about the cold war just 8 miles away!

Mount Rushmore National Memorial - 99 miles

Wind Cave National Park - 132 miles

Jewel Cave National Monument - 148 miles

Devils Tower National Monument - 189 miles

Agate Fossil Beds National Monument - 210 miles

Scotts Bluff National Monument - 247 miles

Fort Laramie National Historic Site - 285 miles

Pipestone National Monument - 325 miles

Theodore Roosevelt National Park - 332 miles

Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument - 318 miles

Check out all of the National Parks in South Dakota along with neighboring National Parks in Iowa, National Parks in Minnesota, National Parks in Montana, Nebraska National Parks, North Dakota National Parks, and Wyoming National Parks

National Park Service Website