If you’re looking for a complete guide to Wind Cave National Park, then you’ve come to the right place.

Keep reading to discover everything you’ll need to know for planning an epic trip to this South Dakota park, including lodging, camping, things to do, information about the area, and more.

Wind Cave National Park

Wind Cave NP is a hidden gem within the National Park system. The park offers the opportunity to take a cave tour, view wildlife including bison and prairie dogs, and learn more about the Black Hills.

About Wind Cave National Park

Wind Cave is amongst the oldest, largest, and longest cave systems in the entire world. While only about five percent of the cave has actually been explored, it is thought to have the highest concentration of the rare box work formations for which it is famed.

These calcite formations look similar to honeycombs and are only found a few other places on earth. The cave is also unique in that it is known to “inhale” and “exhale” during storms when the barometric pressure fluctuates.

If that wasn’t enough to impress, the cave is also home to six underground lakes, and some experts believe that Wind Cave and the nearby Jewel Cave (the third longest cave system in the world) must intersect at various points.

There are a variety of tours available at the park that allow visitors to explore the caves, but there’s so much more to Wind Cave than, well, the cave.

The park boasts nearly 30,000 acres above ground as well, and the stunning swaths of ponderosa pine forest, rolling hills, and mix-grassed prairies are home to some unique flora and fauna that are easy to spot thanks to the wide open topography.

The park is best explored via the 30 miles of trails, or by driving along one of the scenic roads that wind through the area. The park is open year-round, and no matter which season you decide to visit, you’re sure to have an experience that you won’t soon forget.

Is Wind Cave National Park worth visiting?

Yes! Wind Cave is a must for anyone exploring the Black Hills area of South Dakota. There is lots of wildlife, smaller crowds than many of the National Parks, and an incredible cave to go tour.

History of Wind Cave National Park

Wind Cave’s first documented discovery occurred in 1881 when two brothers (Tom and Jesse Bingham) noticed a whistling wind coming from a hole in the ground.

Intrigued, they examined the rock closer, and legend has it that the wind coming from the cave was so strong that it blew one of the brother’s hats right off his head.

Wind Cave is thought to be one of the oldest caves in the world, and long before the brothers came across the cave, it was a sacred place to the Lakota and other tribes that lived in the area.

While no official documents about the cave have been discovered before 1881, Wind Cave has been mentioned in the oral creation story of the Lakota for generations.

The area received National Park designation from Theodore Roosevelt back in 1903, making it one of the oldest national parks in the country, in addition to being the first cave designated as a national park.

Things to know before your visit to Wind Cave National Park

Entrance fee

$0.00, There is no fee to visit the park

Planning a National Park vacation? America the Beautiful/National Park Pass covers entrance fees for an entire year to all US National Park Sites and over 2,000 Federal Recreation Fee Sites.

The park pass covers everyone in the car for per vehicle sites and for up to 4 adults for per-person sites.

Buy on REI.com and REI will donate 10% of pass proceeds to the National Forest Foundation, National Park Foundation and the U.S. Endowment for Forestry & Communities.

Learn more about National Park Passes for parks that have an entrance fee.

Free Entrance Days -Find the five free entrance days the National Park Service offers annually.

Time Zone

MST - Mountain Standard Time

Pets

Pets are allowed at Wind Cave but must be on a leash no longer than 6 feet in length.

Pets are allowed on the grassy area near the visitor center, The Elk Mountain Campground, and on the Prairie Vista Trail and the Elk Mountain Campground Trail.

Pets are not allowed on ranger programs, cave tours, inside public buildings including the visitor center, or on any trail or in the backcountry.

Cell Service

Our cell coverage was spotty in the park. Strong in a few areas and non-existent in others.

Park Hours

The park is open all day, every day. Weather can limit access to specific areas of the park.

Visitor Center and Cave tour hours depend on the time of year.

Wi-Fi

Public Wi-Fi is available at the visitor center.

Insect Repellent

Insect repellent is always a great idea when outdoors, especially if you are around any body of water.

We use Permethrin Spray on our clothes before our park trips.

Water Bottle

Make sure to bring your own water bottle and plenty of water with you. Plastic water bottles are not sold in the park.

Parking

There is a nice size parking area near the visitor center.

Food/Restaurants

There are no restaurants within the park. During our last visit, there was a snack vending machine in the visitor center.

Gas

There are no gas stations within the park.

Drones

Drones are not permitted to be flown within the National Park site.

National Park Passport Stamps

National Park Passport stamps can be found in the visitor center. Make sure to bring your National Park Passport Book with you.

Wind Cave NP is featured in the 2003 Passport Stamp Set.

We like to bring these circle stickers to the park so we don't have to carry our entire Passport Book

Electric Vehicle Charging

EV Charging stations are available in Hot Springs, Keystone, and Custer, South Dakota.

Details about National Park

Size - 33,970

Wind Cave NP is currently ranked at 53 out of 63 National Parks by Size.

Date Established

Established on January 3, 1903, by President Theodore Roosevelt, it was the seventh national park and the first cave to be designated a national park

Visitation

In 2021, Wind Cave NP had 709,001 park visitors.

In 2020, Wind Cave NP had 448,405 park visitors.

In 2019, Wind Cave NP had 615,350 park visitors.

Learn more about the most visited and least visited National Parks in the US

National Park Address

26611 US Highway 385

Hot Springs, SD 57747

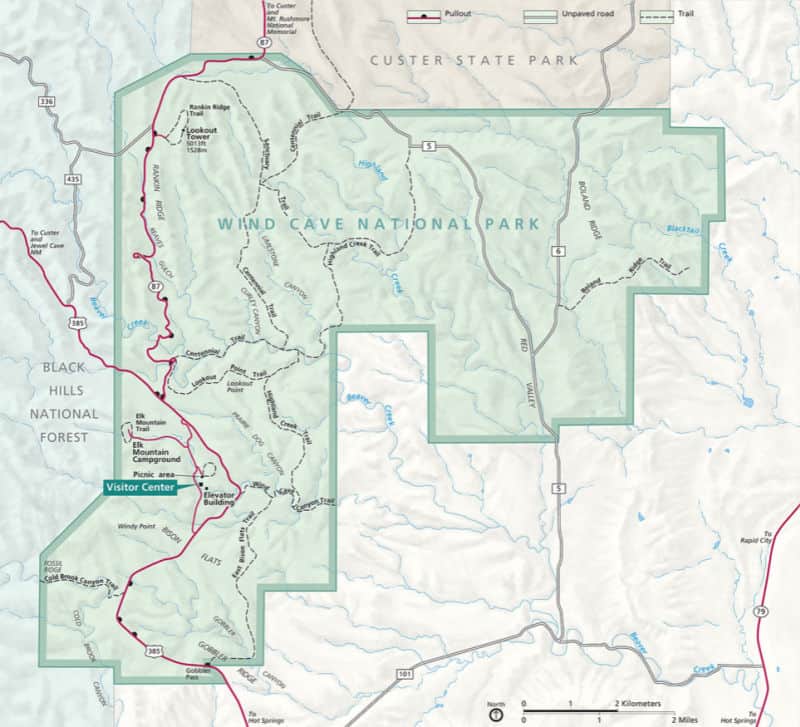

Wind Cave National Park Map

Credit - National Park Service

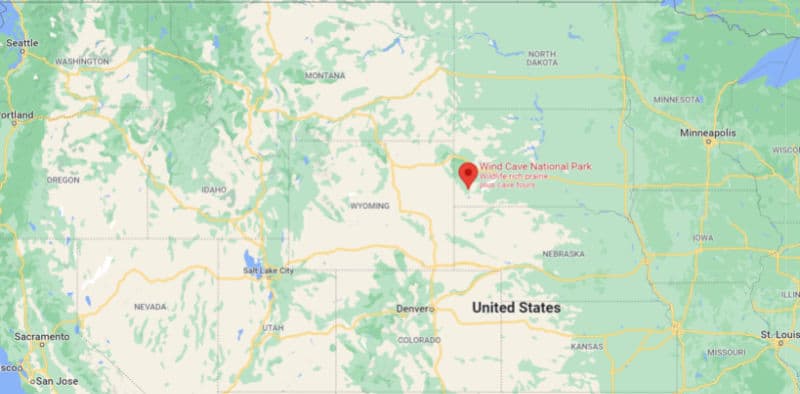

Where is Wind Cave National Park?

Wind Cave National Park is situated in the stunning Black Hills region of southwest South Dakota, about 40 miles south of Rapid City.

The surrounding area is filled with other incredible offerings for visitors interested in seeing more of the Black Hills, including Custer State Park, Mount Rushmore, the Crazy Horse Monument, Sylvan Lake, Jewel Cave, and the scenic Needles Highway.

Estimated distance from major cities nearby

Rapid City, SD - 43 miles

Sturgis, SD - 72 miles

Gillette, WY - 131 miles

Casper, WY - 204 miles

Scottsbluff, NE - 146 miles

Cheyenne, WY - 241 miles

Laramie, WY - 256 miles

Denver, CO - 340 miles

Lincoln, NE - 482 miles

Minneapolis, MN - 613 miles

Kansas City, MO - 675 miles

Estimated Distance from nearby National Park

Badlands National Park - 54 miles

Theodore Roosevelt National Park - 279 miles

Yellowstone National Park - 532 miles

Grand Teton National Park - 452 miles

Glacier National Park - 726 miles

Where is the National Park Visitor Center?

The Visitor Center is located 11 miles north of Hot Springs off U.S. Hwy 385, about ½ mile west of the highway

Getting to National Park

Closest Airports

Rapid City Regional Airport (RAP) - 59 miles

International Airports

Casper-Natrona County International Airport (CPR) - 221 miles

Regional Airports

Western Nebraska Regional Airport (BFF) - 164 miles

Cheyenne Regional Airport (CYS) - 249 miles

Laramie Regional Airport (LAR) - 266 miles

Dickinson Theodore Roosevelt Regional Airport (DIK) - 271 miles

Driving Directions

Do not trust your GPS to find the visitor center. It may lead you to the wrong area.

From Rapid City direct:

- Follow Route 79 south approximately 50 miles to U.S. Route 385.

- Turn right onto U.S. Route 385 North, then continue through Hot Springs.

- Follow U.S. Hwy 385 another 6 miles north and into Wind Cave National Park.

- Once in the park follow signs to the visitor center for cave tours and general park information.

- Follow U.S. Hwy. 16 south and west to U.S. Hwy. 385.

- Turn left on US Hwy. 385 south to Hill City and continue south through Custer City. The park is about 20 miles south of Custer, SD off U.S. Hwy 385.

- Once in the park follow signs to the visitor center for cave tours and general park information.

From Custer State Park:

- Follow State Road 87 south into Wind Cave National Park.

- Once in the park follow signs to the visitor center for cave tours and general park information.

Path inside Wind Cave

Best time to visit Wind Cave National Park.

My personal experience with Wind Cave is that most people go to take a cave tour then they head out to see other parks in the region including Mount Rushmore, Custer State Park, Jewel Cave, and Crazy Horse.

If you spend a little extra time, you will find that the trails here are less crowded than some of the major National Parks and it is filled with wildlife no matter what time of year you visit.

Now Cave tours fill up much faster so make sure you get up early and reserve your spot.

Wind Cave National Park Weather and Seasons

Although Wind Cave National Park is open year-round, severe weather and big crowds mean that some seasons are less desirable for visiting the park

Spring

Spring is a shoulder season at Wind Cave National Park, and it’s amazing that more people don’t choose to visit during this month. The weather is pleasant, and there is a large variety of cave tours offered as well.

If you’re hoping to avoid the busiest months without sacrificing the experience, Spring might be the best time to visit. Keep in mind that this is the wettest season of the year, and rainy days are common during these months.

Summer

Summer is the most popular month to visit Wind Cave National Park. The warmer months also see soaring temperatures and unpredictable weather patterns.

Afternoon thunderstorms are not uncommon in June and July, and sometimes large hail accompanies them. So, keep an eye on the forecast if you choose to visit in the summer.

You’ll also want to arrive at the park plenty early to secure a cave tour, as these sell out quickly during this popular season.

Autumn/Fall

Like the spring, Autumn at Wind Cave National Park means a decrease in temperatures and crowds. This is one of the best seasons to visit the park, as the fall foliage in the Black Hills is seriously spectacular.

Some tours are offered less frequently during the autumn, but if you arrive early enough you should have no problem securing a spot.

Winter

Winter sees the fewest visitors of all the seasons, mostly thanks to the frigid temperatures. This season is also potentially dangerous depending on road conditions, so be sure to check for closures before heading out.

The park is open during the winter despite the snowy conditions, however, and if you’re looking for solitude at Wind Cave National Park, the winter is your best bet.

Depending on the weather, cave tours still operate during the colder months. While tours are less likely to sell out, you should still try to arrive as early as possible to ensure your spot.

Best Things to do in Wind Cave National Park

Cave Tours

Not surprisingly, one of the main draws to Wind Cave National Park is the cave. Not only is Wind Cave one of the largest caves known to man, but it also has the world’s largest concentration of rare boxwork formations.

While you’re here, you’ll find a variety of tours that will take you through the caves, all of which are led by park rangers. Tours are available year-round, but the highest concentration and variety of tours occur during the summer.

There are three main cave tours, in addition to several specialty tours.

Main Tours (available year-round):

Garden of Eden Tour - This is the least strenuous of all the tours at about ⅓ of a mile. Visitors will explore the uppermost part of the cave and some of the rock formations for which Wind Cave is known.

Natural Entrance Tour - This tour is made for the history buffs in your group. Visitors will enter through the man-made entrance and descend to the middle section of the cave. From there they will ride an elevator back up to the surface while you take in views of the boxwork and learn all about the history and early tourism of Wind Cave.

Fairgrounds Tour - At ⅔ of a mile, this tour is more strenuous and has a lot of stairs - about 450 to be exact! You’ll travel through the upper and middle sections of the cave and be privy to the widest variety of formations.

Specialty Tours:

Candlelight Tour - See the cave through the eyes of early explorers, which is to say, by candlelight! This is a moderately strenuous tour.

Wind Cave Tour - This is the most difficult tour available at the park, and it’s for true adventurers only. You’ll put on hard hats and knee caps and wind your way through tight nooks and crannies as you learn the techniques of modern caving.

Unlike the other options, reservations are REQUIRED for this tour, so plan accordingly.

Tickets for tours sell out extremely quickly, especially during the summer and shoulder seasons. Unfortunately, you cannot book tickets in advance, but on a first-come-first-served basis from the Visitor Center. So, plan to arrive plenty early to secure your spot on one of these epic cave tours!

Note that no matter what time of year you visit, the cave temperature hovers around 54 degrees Fahrenheit, so be sure to dress in plenty of layers.

Visitors should also note that some of the tours will lead you through some small nooks and crannies, so those with claustrophobia should consider exploring a different area of the park.

Wildlife viewing

While the cave gets most of the attention be sure not to miss the above-ground areas at the park!

The Black Hills are famed for their stunning vistas and a wide variety of wildlife, and Wind Cave National Park is home to nearly 30,000 acres of land that plays host to some unique creatures.

Some of the full-time residents of this rare, mixed-grass prairie habitat include Bison, Elk, Deer, Pronghorn, Prairie Dogs, Black-foot Ferrets, Badgers, Coyotes, Porcupines, and more.

Some of the best ways for eyeing the park’s wildlife are by hiking and taking a scenic drive along NPS roads 5 and 6.

Junior Ranger Program

If you’re traveling with young ones to Wind Cave National Park be sure to sign them up for the Junior Ranger Program. The program is a fun, hands-on way to learn more about the park, and once they complete the program, they’ll receive a cool badge to remember the experience.

Bird Watching

There are hundreds of species of birds to discover inside of Wind Cave National Park. Summer is one of the best times for birders to visit the park, and there are even guided bird walks available for visits.

Spring and fall are also great times to see migrating species fly over the park.

The area around the Visitor Center is where a large variety of species reside, including warblers, yellow-breasted chat, and western meadowlark, among others.

There is also a unique array of birds around the Elk Campground, so keep your eyes peeled for red-headed woodpeckers and northern flickers. If you’re lucky, you might spot the rare black-backed woodpecker in this area as well.

Hiking in Wind Cave National Park

Always carry the 10 essentials for outdoor survival when exploring.

While the caves are the main draw to Wind Cave National Park, the upper part of the park is just as thrilling as the lower part.

The park boasts about 30 miles of trails in varying lengths and difficulties, and you can also wander off-trail through most of the area as well. Below we’ve highlighted a few of the best hikes in the park.

Rankin Ridge Nature Trail - 1 mile - Easy - Loop

This short route is one of the most popular in the entire park. Not only is it short and relatively easy, but it offers spectacular panoramic views from the park’s highest point. On a clear day, you can see as far as the Badlands! While this hike is rated easy, there is a pretty steady incline up the whole way. Luckily, the uphill part only lasts for about half a mile, and descending back down is a piece of cake!

Elk Mountain Nature Trail - 2.5 miles - Easy - Out & Back

The Elk Mountain Nature Trail is the perfect route for those hoping to see some wildlife while stretching their legs. As you hike, you might catch sight of Bison and Antelope grazing off the trail. Even if you don’t spot any of the park’s full-time inhabitants, this nature trail is a nice little jaunt and never overly crowded.

Wind Cave Canyon Trail - 3.8 mile - Easy - Out & Back

The lovely Wind Cave Canyon Trail meanders through some of the park’s prairie and features beautiful red bluffs, lots of greenery (depending on the time of year you visit), and oftentimes wildlife.

If you’re lucky, you may catch sight of Bison, Mule Deer, Prairie Dogs, and Pronghorn as you meander the trail.

Birding is also excellent along this route, so keep your eyes peeled for red-headed woodpeckers, warblers, yellow-breasted chats, and more.

There is little shade along this route, so be sure to wear plenty of sun protection and bring plenty of water with you - especially in the summer!

Lookout Point & Centennial Tail Loop - 5.2 miles - Moderate - Loop

Lookout Point and Centennial Trail Loop offer hikers a wide variety of scenery and terrain. The route leads through grassland, Prairie Dog towns, and Ponderosa Pine forests.

This trail is longer than others in the park, but the diversity of landscapes makes it well worth the extra mileage. You will also likely see wildlife big and small as you hike. What's not to love?

Highland Creek Trail - 13.6 miles - Hard - Loop

Highland Creek Trail is the longest, and arguably the hardest, trail in Wind Cave National Park. The scenic terrain and solitude are huge draws to this loop, and the chances of seeing wildlife along the route are pretty high.

That being said, you’ll have to work for these perks as the trail is anything but easy thanks to the constant ups and downs of the hilly terrain.

In addition, there is little shade, so be sure to wear lots of sun protection and bring extra water with you - especially if you are hiking during the summer months.

How to beat the crowds in Wind Cave?

The best way to beat the crowds in Wind Cave is by visiting during a shoulder season or off-season. Summer is by far the busiest month at the park, and cave tours sell out extremely quickly.

Tours run year-round, but no matter what season you visit, make sure you arrive early in the morning to ensure your place as spots are limited and available on a first-come-first-served basis.

Where to stay when visiting Wind Cave National Park

There are no National Park Lodges within Wind Cave NP.

There is lodging nearby in Custer State Park.

State Game Lodge at Custer State Park Resort - available to book on Expedia

Comfort Inn And Suites Custer - Take advantage of a free breakfast buffet, laundry facilities, and a gym at Comfort Inn And Suites Custer. For some rest and relaxation, visit the hot tub. In addition to a business center, guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi.

Under Canvas Mount Rushmore - Stay in a glamping tent under the stars

Days Inn by Wyndham Custer - Take advantage of free to-go breakfast, dry cleaning/laundry services, and a gym at Days Inn by Wyndham Custer. Stay connected with free in-room Wi-Fi, and guests can find other amenities such as a 24-hour business center.

Best Western Buffalo Ridge Inn - Consider a stay at Best Western Buffalo Ridge Inn and take advantage of free full breakfast, a terrace, and laundry facilities. Free Wi-Fi in public areas is available to all guests, along with a 24-hour business center and a restaurant.

Rock Crest Lodge And Cabins - At Rock Crest Lodge And Cabins, you can look forward to free continental breakfast, a terrace, and a fireplace in the lobby. For some rest and relaxation, visit the hot tub. Stay connected with free in-room Wi-Fi, and guests can find other amenities such as a business center.

Click on the map below to see current rates for hotels and vacation rentals near Wind Cave NP

Wind Cave National Park Camping

For a fun adventure check out Escape Campervans. These campervans have built in beds, kitchen area with refrigerators, and more. You can have them fully set up with kitchen supplies, bedding, and other fun extras. They are painted with epic designs you can't miss!

Escape Campverans has offices in Vancouver, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Denver, Chicago, New York, and Orlando

Elk Mountain Campground is located within the park.

Campgrounds near Wind Cave include

Hidden Lake Campground and Resort - 7 miles away in Hot Springs, SD

This campground has RV and Tent Sites with waterfront views.

Larsson's Crooked Creek Resort - 24 miles away Hill City, SD

This campground offers tent and RV sites along with lodging

Sturgis Hideaway Campground - 59 miles away in Sturgis, SD

This campground offers RV and Tent Sites along with lodging.

Check out additional campgrounds near Wind Cave here.

Parks near National Park

Minuteman Missile National Historic Site

Devils Tower National Monument

Mount Rushmore National Memorial

Check out all of the National Parks in South Dakota along with neighboring National Parks in Iowa, National Parks in Minnesota, National Parks in Montana, Nebraska National Parks, North Dakota National Parks, and Wyoming National Parks