Hawaii Volcanoes National Park is located on the big island of Hawaii and offers an experience unlike any you are likely to find anywhere else in the world.

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park

If you have ever marveled at nature's beauty, been curious about how the islands were formed, or simply wish to see something truly unique, set aside a few hours on your vacation to explore Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. You will not be disappointed.

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park is located about thirty miles from Hilo and ninety-six miles from Kona so it is an easy drive that won't wear you down.

About Hawaii Volcanoes National Park

Hawaii's Big Island is home to a national park unlike any other in the United States.

Spread along its eastern side, southwest of the town of Hilo, is a science fiction landscape of deep craters, crusty cinder cones, steaming vents, pumice heaps, and blackened lava fields up to 3 miles wide, dotted with mounds of vegetation. This is Hawaii Volcanoes National Park.

It is home to two of the world's most active volcanoes, Kilauea and Mauna Loa. From the molten rivers of lava pouring into the sea from Kilauea to the snowfields on the summit of Mauna Loa, it encompasses fire and ice.

Many people are surprised by their first view of a Hawaiian volcano.

Instead of the steep, cone-shaped peaks of such majestic volcanoes as Washington State's Mount Rainier and Mount Fuji in Japan, Hawaiian volcanoes slope gently, rising to a pit rather than a point: the giant chasm, called a caldera, the Spanish word for cauldron, looks like a warrior's shield lying face up on the ground.

Scientists call these domed mountains shield volcanoes. Their summits collapsed over a long period of time after repeated eruptions spewed out their insides.

Is Hawaii Volcanoes National Park worth visiting?

YES! The opportunity to visit an active volcano is a National Park Bucket List moment.

We have seen hot lava flowing into the Pacific Ocean, flown over an active lava flow, and gazed in awe at the red hue from the caldera.

Each of these moments has been a reminder of just how amazing this park truly is.

History of Hawaii Volcanoes National Park

The park encompasses about 333,000 acres of land – bigger than the sister island of Molokai. And it's still growing. Lava flowing from Kilauea has added 600 acres in less than 20 years.

Hawaii itself was created by volcanoes. This string of eight large islands and 124 smaller ones emerged from tons of magma, built up from fiery eruptions on the ocean floor over 70 million years.

Mauna Loa is the highest and most massive mountain on earth. It measures 56,000 feet from its base on the ocean floor, making it nearly twice as high as Mount Everest. It last erupted in 1984.

A year earlier, Kilauea began a series of eruptions that are still ongoing, making them the longest in recorded history. Hot lava bubbles through the earth's crust, or explodes in fiery fountains. Slow-moving trails of lava creep down the mountainside, scorching everything in their path.

Finally, they pour over cliffs into the sea, sending up clouds of gas.

Things to know before your visit to Hawaii Volcanoes National Park

Before hopping in your car and making the trip it is essential you first check the status of the park.

As you are visiting an active and dormant volcano nature works on its own schedule. There are times when part of the park is closed down and others when the entire park is closed due to safety issues.

Even if there is no "Significant" volcanic activity air quality is a major concern as sulfur dioxide emissions are dangerous, and this is the usual reason the park experiences closures.

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park Entrance Fee

Park entrance fees are separate from camping and lodging fees.

Park Entrance Pass - $30.00 Per private vehicle (valid for 1-7 days from the date of purchase)

Park Entrance Pass - Motorcycle - $25.00 Per motorcycle (valid for 1-7 days from the date of purchase)

Per-Person Entrance Pass - $15.00 Visitors 16 years or older who enter on foot, bicycle, or as part of an organized group not involved in a commercial tour.

Annual Park Entrance Pass - $55.00, Admits pass holder and all passengers in a non-commercial vehicle. Valid for one year from the month of purchase.

$40.00-$75.00 for Commercial Sedan with 1-6 seats and non-commercial groups (16+ persons)

$75.00 for Commercial Van with 7-15 seats

$100.00 for Commercial Mini-Bus with 16-25 seats

$200.00 for Commercial Motor Coach with 26+ seats

Learn more about National Park Passes for parks that have an entrance fee.

$80.00 - For the America the Beautiful/National Park Pass. The pass covers entrance fees to all US National Park Sites and over 2,000 Federal Recreation Fee Sites for an entire year and covers everyone in the car for per-vehicle sites and up to 4 adults for per-person sites.

Buy your pass at this link, and REI will donate 10% of pass proceeds to the National Forest Foundation, National Park Foundation, and the U.S. Endowment for Forestry & Communities.

National Park Free Entrance Days -Mark your calendars with the five free entrance days the National Park Service offers annually.

Time Zone

Hawaii-Aleutian Standard Time

Time zone in Hawaii (GMT-10)

Hawaii does not follow daylight savings time so depending on the time of year can determine the time difference between Hawaii and other parts of the U.S.

Pets

Pets are prohibited in all of the undeveloped areas of the Park. This includes all designated wilderness and all trails.

Pets are allowed in developed areas of the park; including paved roadways, parking areas, and Namakanipaio Campground.

However, please note: parking and camping areas are sites where the endangered Nene goose frequent.

Cell Service

Most of the park has good cellular reception (with the exception of the backcountry).

Reception is spotty on a section of Chain of Craters Road near Maunaulu and at the end of Chain of Craters Road, depending on your carrier.

Park Hours

Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park is open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, as well as all holidays.

Kahuku Unit is located on Hwy 11, between mile markers 70 and 71. The unit is 70.5 miles south of Hilo. The Kahuku Unit is open Thursday through Sunday from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. and is closed on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday.

Wi-Fi

The park currently offers public WiFi access. The Volcano House Hotel offers in-room WiFi access.

Parking

Parking lots can fill quickly within the park. You may have to circle a few times or return later in the day for main attractions.

Kilauea Visitor Center Parking - 125 total/ 9 oversize

Uēkahuna Parking - 69 total/ 7 oversize

Kilauea Overlook Parking - 36 total/ 2 oversized

Kilauea Iki Overlook Parking Lot - 64 total/ 0 oversized

Nahuku (Thurston Lava Tube) - 14 total/ 2 oversized

Pu'upua'i Parking Lot - 28 total/ 0 oversized

Devastation Trail Parking Lot - 30 total/ 0 oversized

End of Chain of Craters Road Parking Lot - 37 total/ 0 oversized

Food/Restaurants

There are a couple of restaurant options at the Volcano House.

The Rim at Volcano House serves breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Uncle George's Lounge offers breakfast, lighter fare, an afternoon snack, or a late-night treat.

If you are staying at the Volcano House you can also enjoy room service.

Gas

There are no gas stations within the park.

Electric Vehicle Charging

There is 9 electric vehicle charging stations within a 30-mile radius of Volcano, HI 96785.

Drones

Drones are NOT allowed within Hawaii Volcanoes National Park.

Don't forget to pack

Don't forget to pack

Insect repellent is always a great idea outdoors, especially around any body of water.

We use Permethrin Spray on our clothes before our park trips. Please read my article on preventing biting insects while enjoying the outdoors.

Sunscreen - I buy environmentally friendly sunscreen whenever possible because you inevitably pull it out at the beach.

Bring your water bottle and plenty of water with you. Plastic water bottles are not sold in the park.

Sunglasses - I always bring sunglasses with me. I personally love Goodr sunglasses because they are lightweight, durable, and have awesome National Park Designs from several National Parks like Joshua Tree, Yellowstone, Hawaii Volcanoes, Acadia, Denali, and more!

Click here to get your National Parks Edition of Goodr Sunglasses!

Binoculars/Spotting Scope - These will help spot birds and wildlife and make them easier to identify. We tend to see waterfowl in the distance, and they are always just a bit too far to identify them without binoculars.

Details about Hawaii Volcanoes National Park

Size - 335,259 Acres

Hawaii Volcanoes NP is currently ranked at 24 out of 63 National Parks by Size.

The park includes 94 miles of roads; 155 miles of marked trails; 123,100 acres of legislated wilderness; 121,015 acres of eligible wilderness; 7,850 acres potential wilderness.

Date Established

On August 1, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed the country's 13th national park into existence.

Visitation

In 2020, Hawaii Volcanoes NP had 589,775 park visitors.

In 2019, Hawaii Volcanoes NP had 1,368,376 park visitors.

Learn more about the most visited and least visited National Parks in the US

National Park Address

1 Crater Rim Drive

Hawaii National Park, HI 96718

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park Map

For a detailed map, we use the National Geographic Trails Illustrated Maps. They can be found on Amazon.

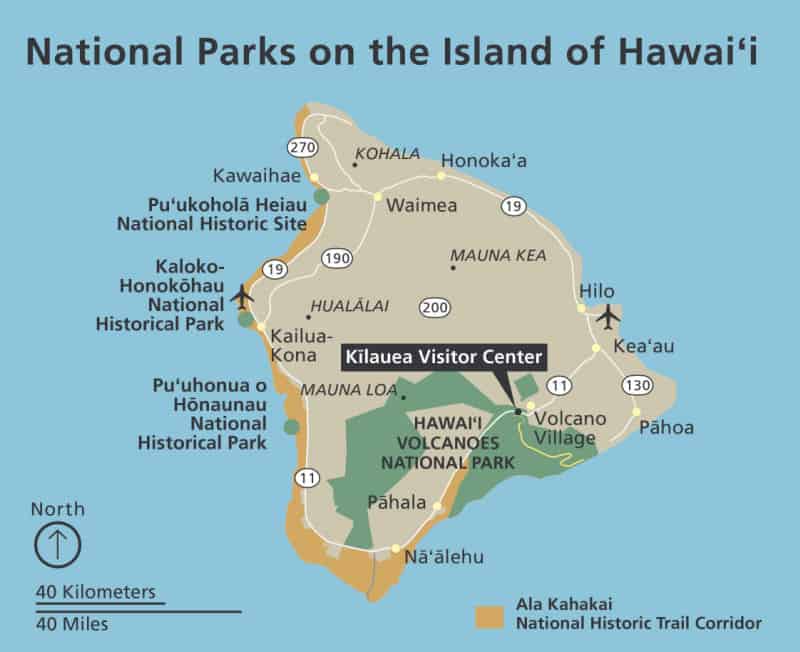

Where is Hawaii Volcanoes National Park?

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park is located on the Big Island of Hawaii

Estimated distance from major cities nearby

Kona, Hawaii - 110 miles

Hilo, Hawaii - 35 miles (Check out this great Hilo Travel Guide)

Estimated Distance from nearby National Park

Haleakala National Park is located on the island of Maui.

Where is the National Park Visitor Center?

Kilauea Visitor Center - Open 9 am to 5 pm daily

This visitor center is a great place to stop for the latest information on the current eruption, hiking information, things to do, and the daily schedule of ranger-led activities.

The featured film, "Born of Fire, Born of the Sea", is shown on-the-hour in the visitor center auditorium, starting at 9:00 a.m. with the last showing at 4:00 p.m.

Twice a day at 11:30 a.m. and 2:30 p.m., the 1959 eruption video of Kīlauea Iki is featured in the auditorium.

Jagger Museum -Closed Indefinitely due to damage from the volcano

Thomas A. Jaggar Museum is located along Crater Rim Drive, 3 miles from the Kīlauea Visitor Center.

Getting to Hawaii Volcanoes National Park

Closest Airports

Hilo International Airport - ITO

Kona International Airport - KOA

Driving Directions

You can reach the park from either the Kona side or the Hilo side of the island. Hilo is approximately 30 miles from the park entrance.

From Kona, it is 96 miles. If you are leaving from Kona, we suggest going towards South Point and visiting the Punalu'u Bake Shop! Have a lilikoi malasada!

You will not be disappointed.

From Hilo: 30 miles southwest on Highway 11 (a 45-minute drive);

From Kailua-Kona: 96 miles southeast on Highway 11 (2 to 2 ½ hour drive), or 125 miles through Waimea and Hilo via highways 19 and 11 (2 ½ to 3 hours).

From Waikoloa: 90 miles southeast on Highway 200 (2 hour drive).

There is no public transportation available within Volcanoes National Park.

Best time to visit Hawaii Volcanoes National Park

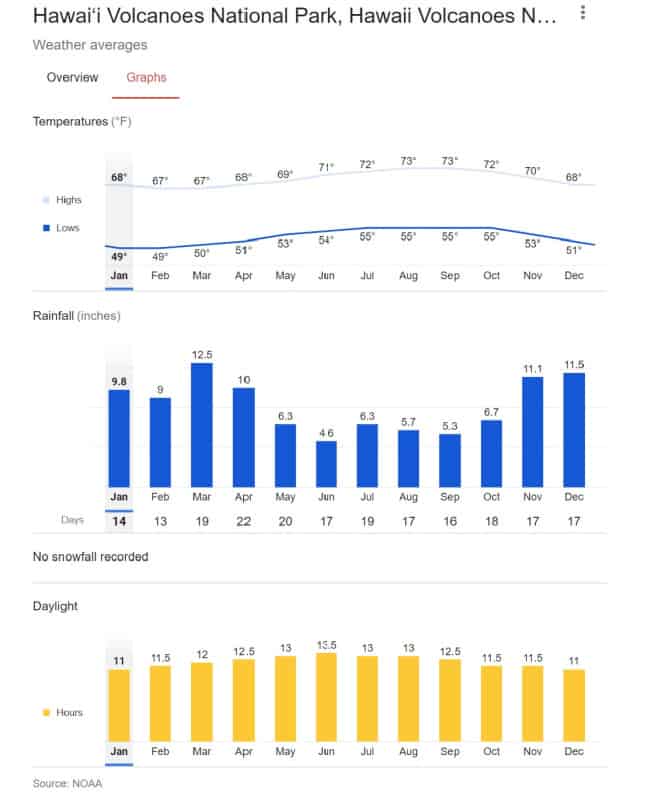

Hawaii is different for the fact that the weather does not change much from day to day. How the weather will change is by going to different parts of the island. A great example is the difference between Hawaii Volcanoes and Kona where the average high temperature year round is in the 80's.

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park Weather and Seasons

You can expect all the seasons in Hawaii Volcanoes NP sometimes all on the same day.

Fog is common and so is rain. The elevation at the visitor center is approximately 4000 feet. This means that it is much cooler here than where most tourists coming from the Kona side.

Every time we have visited the park it has poured rain. Sometimes all day rain other times just quick burst of a torrential downpour.

My wife likes to tell me the story about visiting the park when she was studying at University of Hawaii, Hilo and their professor told them to pack garbage bags.

They thought they were going to be doing scientific sampling for class. You can imagine my wife's surprise when the professor told them to wear the garbage bags because the rain was coming.

When it comes to seasons Hawaii really has two...wet or dry.

My best advice is come with raingear and dress in layers. After spending a few days on the Kona side of the island, I was quickly chilled at Hawaii Volcanoes.

Kilauea Volcano Eruption

Eruptions occur sporadically and are a very popular attraction when it does happen. Just remember to first check the park alerts for updated information as there may be temporary/permenant closures and health warnings.

The park can become very busy and parking can become very difficult. If you plan to visit the park and view the glow at night, please be prepared for it to be packed!

Expect traffic delays, packed parking lots, crowds, and walking to reach an overlook. Make sure to pack a flashlight.

During the day, visitors can see the volcanic gas and steam from the eruption within Halemaʻumaʻu crater.

Eruptions can change by the minute, hour, and day!

Viewing is dependent on eruption activity and weather conditions.

PLEASE Remember that this land is sacred and to follow all rules.

Best Things to do in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park

The park is one of the few places on Earth where volcanic forces can be safely seen up close. It has been declared an International Biosphere Reserve and World Heritage Site.

Here are some of the park's other highlights:

Crater Rim Road

11-mile road circles the 4,000-foot summit of Kilauea. It crosses the caldera floor and has scenic trails and marked stops that look out over steaming craters and other phenomena.

Chain of Craters Road

A steep 18.8-mile descent down Kilauea's southern slopes gives fantastic views of lava fields, craters, and the coastline far below.

No food, water, or fuel is available along the Chain of Craters Road. Vault-type toilets are available at the Maunaulu parking area and the end of the road.

Sulphur Banks

Florescent yellow rocks and the putrid smell of rotten eggs mark these steam vents where sulfuric gases are released.

Be prepared for the smell!

Nahuku - Thurston Lava Tube

Formed by molten lava, this natural tunnel is high enough to walk through standing upright.

Wildlife viewing

Keep an eye out for Nene Geese wandering in the park. Nēnē (the Hawaiian goose) is an endangered species.

The park provides refuge for seven threatened species including the nēnē (Hawaiian goose) and 47 endangered species which include honu‘ea (hawksbill turtle), ‘ua‘u (Hawaiian petrel), and the Ka‘ū silversword.

Junior Ranger Program

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park offers a couple of different Junior Ranger Programs. You can check out the programs ahead of your trip and print them from home if you would like.

To learn more about the Hawaii Volcanoes Junior Ranger Program visit this page.

Guided Tours

From Hilo - Helicopter ride over the park and waterfalls

Soar over Volcano National Park on this helicopter tour from Hilo. Marvel at views of the Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa volcanos. Fly over waterfalls that plunge into lush vegetation.

From Kona - Mauna Kea Stellar Explorer

For an out-of-this-world experience, check out Maunakea Stellar Explorer. This thrilling adventure features nighttime astronomical observing as well as safe daytime solar viewing, with all ages welcome.

From Kona or Waikoloa - Volcano Discovery Tour

Journey to Hawaii Volcanoes National Park for an in-depth volcano experience. Your certified guide will share a mix of natural and cultural history about Hawaii's formation, illuminating the stories behind the ever-changing landscape of the Big Island.

Kilauea Volcano Hiking Tour - Experience a volcano up close and personal on the Big Island of Hawaii, and discover the natural and cultural history about the island’s formation.

Twilight Volcano and Stargazing Tour - Experience the Big Island’s most spectacular natural splendors on this small-group tour and discover the history, cultures, and geology of the island. Visit a Kona Coffee Farm and the magnificent Hawaii Volcanoes NP.

Volcano NP Tour with Lunch - Join a full-day nature tour offering an in-depth look at Hawaii. Discover diverse landscapes as you explore Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, Waipio Valley waterfalls, and Punalu’u Black Sand Beach.

Volcano NP Group or Private Hiking Tour - Step into the caldera of an active volcano on a group or private hike in Hawai'i Volcanoes NP. Trek through Hawaiian forests and Kilauea Iki Crater to reach the iconic Thurston Lava Tube.

Volcano NP E-Bike Ride with GPS Guide - Take a GPS E-bike Tour of the Hawaii Volcanoes NP and the Lava Viewing Area using your smartphone. Embark on an adventure packed with fun bike trails and roads.

Door Off Helicopter ride over Volcano and the Rainforest - There is no better vantage point than a helicopter and there is no bigger thrill than leaving the doors behind so there is nothing between you and the sights. On this scenic flight tour, soar over iconic waterfalls and glowing lava flow.

From Kona - Helicopter Tour with private landing in a secluded location.

Take a helicopter tour over Big Island for views of Hawaii’s famous volcanoes and mountains. Top it off with a private landing in a secluded location so you can enjoy your own piece of paradise.

Hiking in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park

Always carry the 10 essentials for outdoor survival when exploring.

140 miles of hiking trails wind through a variety of terrain, from the twisted landscapes of crater rims and hardened lava fields to the lush rainforest and tropical beaches.

If you plan on hiking within the park make sure you are wearing sturdy hiking boots. The lava can be very uneven and rough to hike on.

One of our favorite trails is the Pu’u Loa Petroglyphs Trail

How to beat the crowds in Hawaii Volcanoes?

One off the best ways to beat the crowds is to arrive early and plan to stay late in the park. Sunrise and sunset are epic in the park.

Head to Chain of Craters Road and explore the 19 miles of roadways as soon as you enter the park.

Visit the Kahuku section of the park. It is free and never crowded. This portion of the park is open Wednesday through Sunday from 9 am to 4 pm.

The Merrie Monarch Festival ( A weeklong festival featuring the internationally acclaimed hula competition) is held in April each year in Hilo. This can lead to increased visitation for the week of the event.

During spring break, there can also be an increase in visitation.

Where to stay when visiting Hawaii Volcanoes National Park

Volcano House is the only National Park Lodge within Hawaii Volcanoes NP.

The lodge is perched on the rim of Kilauea and offers stunning views of the active volcano.

Hawai'i Volcanoes Lodge Company operates rustic camper cabins and campsites at the Nāmakanipaio campground. The cabins sleep 4 (1 double bed and two bunk-style twin beds). Each cabin has a picnic table, an outdoor barbecue grill, and an outdoor fire pit. Reservations are required.

Kīlauea Military Camp This recreational facility is for active duty and retired military, reservists, DoD civilians, families, and sponsored groups. Call 808-967-8333 or visit http://www kmc-volcano.com/ for more information.

Lodging near the park includes:

Colony I at Sea Mountain - Guests of this beach condo building will appreciate convenient onsite amenities such as a spa tub or barbecue grills. Each condo provides a kitchen with a refrigerator, a stovetop, a microwave, and a dishwasher. Guests will appreciate conveniences like a washer/dryer and a coffee/tea maker, while a TV with cable channels and a DVD player provide a bit of entertainment.

The Inn at Kulaniapia Falls - 3.5-star boutique bed & breakfast by the river. Take advantage of a terrace, a garden, and a library at The Inn at Kulaniapia Falls. Active travelers can enjoy hiking/biking, rock climbing, and a ropes course at this bed & breakfast. Guests can connect to free Wi-Fi in public areas.

Outrigger Kona Resort - 4-star family-friendly resort by the ocean. In addition to shopping on site and a coffee shop/café, guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi.

Grand Naniloa Hotel Hilo - a Doubletree by Hilton - 4-star hotel in the heart of Keaukaha. Active travelers can enjoy cycling, snorkeling, and fishing at this hotel. Be sure to enjoy a meal at Hula Hulas, the onsite restaurant. Enjoy the 24-hour gym, as well as activities like boat tours, rowing/canoeing, and sailing. Stay connected with free in-room Wi-Fi, and guests can find other amenities such as dry cleaning/laundry services and a fireplace in the lobby.

You can also stay outside of the park in Hilo, Hawaii and nearby smaller communities.

Click on the map below to see additional vacation rentals and lodging near the park.

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park Camping

There are two drive-in campgrounds in Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park, Nāmakanipaio and Kulanaokuaiki.

Nāmakanipaio Campground has restrooms with water and moderately accessible campsites.

Kulanaokuaiki Campground has an accessible toilet but no water.

Travel Tips for Hawaii Volcanoes NP

Ensure you bring sunscreen (the reflection off the black lava fields will get you even if you wear a hat) and wear appropriate clothing.

No flip-flops or sandals if you plan on hiking and a windbreaker or a warmer layer that you can slip on; the volcano's summit can be chilly and windy.

Your cell phone service will most likely be spotty if it works within the park.

Be prepared for rain at any time. When it does rain, it comes down! Rain jackets or garbage bags are a great thing to have with you.

Keep an eye out for Nene Goose on the side of the road and in parking lots. The Nene is protected and should not be fed or touched.

For current lava conditions and road closures, check out the Hawaii Volcanoes Website or call 808-985-6000 between 9 am-5 pm.

Resources for more information about the lava flows:

USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory

by phone at: (808) 967-8862

by web at http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/activity/kilaueastatus.php

County of Hawai'i Civil Defense

by phone at: (808) 935-0031 (7:45 am - 4:30 pm)

by web at http://www.hawaiicounty.gov/active-alerts/

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park Facts

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park was established in 1916

The volcano has been erupting since 1983, adding about 500 acres of land and destroying 187 structures.

Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park has been designated as an International Biosphere Reserve (1980) and a World Heritage Site (1987).

Hawai‘i Volcanoes extends from sea level to 13,677 feet (4,169 meters) and encompasses the summits and rift zones of two of the world’s most active volcanoes, Kīlauea and Mauna Loa.

Volcanic features include calderas, pit craters, cinder cones, spatter ramparts, fumaroles, solfataras,

pāhoehoe and ‘a‘ā flows, tree molds, black sand beaches, and thermal areas.

Parks near Hawaii Volcanoes National Park

Kaloko-Honokohau National Historical Park

Pu'ukohola Heiau National Historic Site

Puuhonua o Honaunau National Historical Park - City of Refuge

Ala Kahakai National Historic Trail

Check out all of the National Parks in Hawaii

National Park Service Website