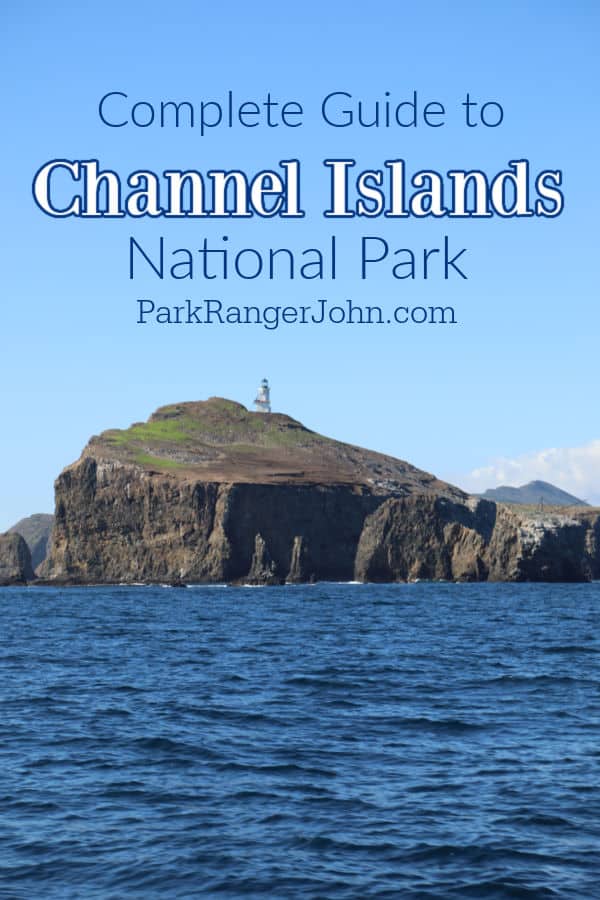

Complete guide to Channel Islands National Park in California, including how to get to the park, things to do, history, and so much more.

Channel Islands National Park

The Channel Islands are an archipelago of eight islands lying off California’s southern coast. The national park encompasses five of these islands and a large swath of protected underwater areas off the coast.

The park is home to numerous endangered and endemic species, in addition to epic views, scenic hiking trails, and some of the largest sea caves in the world.

About Channel Islands National Park

The islands are only accessible via ferry or plane, so taking a trip to Channel Islands National Park will take some planning.

Each island is different in size, scope, and scenery, so take some time to read up on each of them before deciding which area of the park you want to discover.

The four northernmost, Anacapa, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, and San Miguel, form an east-west chain. The distance between any two of them is not more than five miles.

Together with tiny Santa Barbara island 40 miles to the south, these bits of land and the sea around them make up Channel Islands National Park.

It is not surprising that these islands look like mountains, because they are. Though only their tops are visible, if the ocean were drained we would see the base of the mountains as well as smaller peaks, hills, and valleys, all strikingly similar to the mainland terrain.

The similarity is more than superficial: the four northern islands are actually the seaward extension of the Santa Monica Mountains that became four separate pieces when glaciers melted, the level of the ocean rose, and water flowed into the low-lying areas.

Anacapa Island

Anacapa Island is the closest to the mainland and can be reached with a quick, one-hour ferry ride from Ventura. Although there are only about two miles of trails, the view from this short route offers up some of the best views in the park.

This island is also popular with nesting seabirds, so you may want to skip Anacapa if you’re not a birding fanatic.

Santa Cruz Island

Santa Cruz Island is one of the most popular outposts in the park. It’s the largest island in the park, and it also offers pleasant weather conditions, tons of trails, and fun activities like kayaking, diving, and wildlife watching.

Santa Cruz has two anchorage points, so travel time varies between one and two hours depending on where you are headed.

San Miguel Island

San Miguel Island is one of the most challenging areas to get to, and therefore sees some of the fewest crowds in the park.

If you want to enjoy the solitude of this area, be sure you are prepared for heavy winds, as these are almost a guarantee no matter what time of year you visit San Miguel.

This outlying island is home to one of the largest sea lion congregations in the world, along with a massive hiking trail that offers visitors incredible panoramic views.

The ferry takes about three hours from Ventura, and you’ll likely have to camp out here for at least one night as there is usually only one trip from the mainland each day.

Santa Barbara Island

Santa Barbara is the smallest and most outlying island in the park and takes about three hours to reach via ferry.

Because it is so far off the beaten path, it offers some of the best wildlife viewing opportunities, along with some great kayaking, diving, and hiking options.

Santa Rosa Island

Santa Rosa is the second-largest island in the park. Famed for its stunning beaches, Santa Rosa is a popular choice for park visitors. This is also a great place for wildlife watching and hiking.

However, those who want to visit this stunning spot should be ready for strong winds and a 2.5-hour ferry ride.

Is Channel Islands National Park worth visiting?

Although it will take some planning, Channel Islands National Park is absolutely worth visiting.

History of Channel Islands National Park

The Channel Islands have been home to a variety of peoples for over 13,000 years. The first inhabitants of the islands are thought to be the Chumash and Tongva people, though archaeologists have found human bones predating these ancient tribes.

The islands were discovered and conquered by the Spanish in the 16th century. Since then, the islands have played host to shipwrecked pirates, ranchers, and researchers.

The Santa Barbara and Anacapa islands have been protected as a national monument since 1938, and in 1980 the other three islands were added, and the area was dubbed a national park.

Things to know before your visit to Channel Islands National Park

Channel Islands National Park Entrance Fee

Park entrance fees are separate from camping and lodging fees.

Channel Islands National Park does not charge an entrance fee!

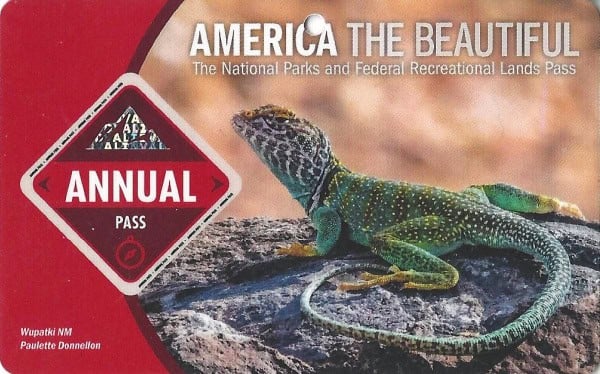

Learn more about National Park Passes for parks that have an entrance fee.

$80.00 - For the America the Beautiful/National Park Pass. The pass covers entrance fees to all US National Park Sites and over 2,000 Federal Recreation Fee Sites for an entire year and covers everyone in the car for per-vehicle sites and up to 4 adults for per-person sites.

Buy your pass at this link, and REI will donate 10% of pass proceeds to the National Forest Foundation, National Park Foundation, and the U.S. Endowment for Forestry & Communities.

National Park Free Entrance Days -Mark your calendars with the five free entrance days the National Park Service offers annually.

Time Zone

Pacific Time Zone

Pets

Pets are not allowed in the park.

Cell Service

Cell service is available at the mainland park visitor center.

On the islands the service is spotty at best.

Park Hours

The park is open 24 hours a day. Visitor services hours depend on time of year.

Wi-Fi

There is no Wi-Fi available in the park.

Parking

There is a large parking lot near the main visitor center. It offers great access to both the visitor center and the beach.

There is a nice size parking area near Island Packers ferry to the islands.

Food/Restaurants

There are no restaurants within the park.

Gas

There are no gas stations within the park.

Drones

Drones are not permitted within National Park Sites.

Don't forget to pack

Insect repellent is always a great idea outdoors, especially around any body of water.

We use Permethrin Spray on our clothes before our park trips. Please read my article on preventing biting insects while enjoying the outdoors.

Sunscreen - I buy environmentally friendly sunscreen whenever possible because you inevitably pull it out at the beach.

Bring your water bottle and plenty of water with you. Plastic water bottles are not sold in the park.

Sunglasses - I always bring sunglasses with me. I personally love Goodr sunglasses because they are lightweight, durable, and have awesome National Park Designs from several National Parks like Joshua Tree, Yellowstone, Hawaii Volcanoes, Acadia, Denali, and more!

Click here to get your National Parks Edition of Goodr Sunglasses!

Binoculars/Spotting Scope - These will help spot birds and wildlife and make them easier to identify. We tend to see waterfowl in the distance, and they are always just a bit too far to identify them without binoculars.

Electric Vehicle Charging

There is an EV Charging Station available at Island Packers Cruises.

Details about Channel Islands National Park

Size - 249,354 acres

Channel Islands NP is currently ranked at 27 out of 63 National Parks by Size.

Date Established

April 26, 1938 - President Franklin D. Roosevelt designated Anacapa and Santa Barbara Islands as Channel Islands National Monument.

February 9, 1949 - President Harry S. Truman added 17,635 acres to the park.

March 5, 1980 - President Jimmy Carter signed legislation establishing Channel Islands National Park.

Visitation

In 2021, Channel Islands NP had 319,252 park visitors.

In 2020, Channel Islands NP had 167,290 park visitors.

In 2019, Channel Islands NP had 409,630 park visitors.

Learn more about the most visited and least visited National Parks in the US

National Park Address

1901 Spinnaker Drive

Ventura, CA 93001

Channel Islands National Park Map

For a more detailed map we really like the National Geographic Trails Illustrated Maps available on Amazon.

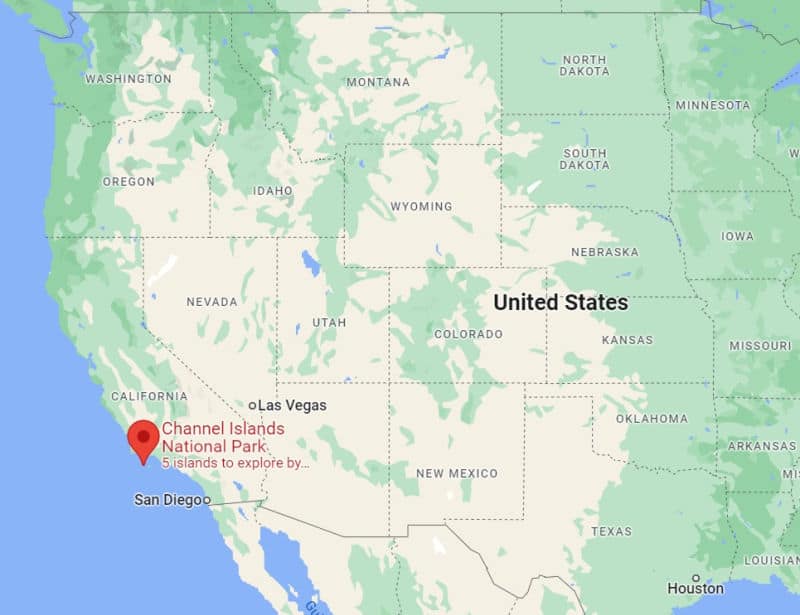

Where is Channel Islands National Park?

Channel Islands NP is located off the coast of Southern California near Santa Barbara.

Estimated distance from major cities nearby

Oxnard, CA - 50 miles

Ventura, CA - 45 miles

Santa Barbara, CA - 36 miles

Thousand Oaks, CA - 68 miles

Santa Clarita, CA - 88 miles

Pasadena, CA - 106 miles

Los Angeles, CA - 100 miles

Long Beach, CA - 104 miles

San Diego, CA - 185 miles

San Francisco, CA - 296 miles

Estimated Distance from nearby National Park

Joshua Tree National Park - 234 miles

Sequoia National Park - 191 miles

Kings Canyon National Park - 217 miles

Pinnacles National Park - 188 miles

Yosemite National Park - 270 miles

Grand Canyon National Park - 310 miles

Death Valley National Park - 241 miles

Where is the National Park Visitor Center?

Robert J. Lagomarsino Visitor Center

This visitor center includes a small store, a display of marine aquatic life, and exhibits featuring the unique character of each park island. Visitors also will enjoy the 25-minute park movie, “A Treasure in the Sea,” shown throughout the day in the auditorium.

The fully accessible visitor center is open 8:30 am until 5 pm daily. The visitor center is closed on Thanksgiving and December 25th. Weekends and holidays at 11 am and 3 pm rangers offer a variety of free public programs about the resources of the park.

Click here for programs and events scheduled at the visitor center.

1901 Spinnaker Drive

Ventura, CA 93001

(805) 658-5730

Outdoors Santa Barbara Visitor Center

This visitor center offers visitors information about Channel Islands National Park, Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary, Santa Barbara Maritime Museum, and the City of Santa Barbara.

Open 10 am until 5 pm. Closed every Wednesday, Christmas Day, New Year's Day, Thanksgiving Day, and the First Friday in August for Fiesta.

113 Harbor Way 4th Floor

Santa Barbara, CA 93109

(805) 884-1475

Anacapa Island Visitor Center

34.01542353356743, -119.36363606265787

Santa Barbara Island Visitor Center

33.48053267857925, -119.02958027130204

Scorpion Ranch Visitor Center on Santa Cruz Island

34.0486528179359, -119.55850509512013

Santa Rosa Island Visitor Contact Station

34.048877535832126, -119.55848139754222

San Miguel Island Ranger and Visitor Contact Station

34.03885353639919, -120.35174085240293

Getting to Channel Islands National Park

Closest Airports

Los Angeles International Airport (LAX)

Burbank Bob Hope Airport (BUR)

Santa Barbara Airport (SBA)

Camarillo and Oxnard Airport (OXR)

Driving Directions

While you may not be able to drive to or around the islands, you can access two of the visitor centers on the mainland.

The Robert J. Lagomarsino Visitor Center is located in the harbor of Ventura off of Freeway 101.

The Outdoor Santa Barbara Visitor Center is located in the harbor of Santa Barbara off of Freeway 101.

Island Transportation

The park islands are only accessible via private boat or park concessionaire boats operated by Island Packers.

Most ferries leave from the Ventura Harbor, and services range depending on your final destination and which time of year you are visiting.

Be sure to plan ahead and check out the park website for more info on getting to the islands. Ferry tickets for spring and summer often sell out, so try to book at least two months in advance if you plan on visiting during the busy season.

Best time to visit Channel Islands National Park

The park is technically open year-round, but the weather and sea conditions can lead to closures and canceled ferries.

This is especially true during the winter, but no matter what time of year you are visiting, be sure to check for closures and take a peek at the weather forecast before starting your journey out to Channel Islands National Park.

Weather and Seasons

Spring

Spring is a great time to visit Channel Islands National Park, especially if you’re hoping to avoid the crowds (spring break is the exception here).

It may be a bit rainy during this time of year, but the showers give way to beautiful blooming wildflowers across the islands.

Summer

Summer is one of the busiest seasons at the park. The warm weather brings large crowds, so don’t expect to have the islands to yourself in this season. If you plan on camping, be sure to book well in advance, as permits go quick in the summer.

Fall

Fall is perhaps the best time to visit Channel Islands National Park, especially during September and October. The weather is great, and the big summer crowds have mostly thinned out.

The water conditions are also usually at their warmest and calmest during the fall, which makes it the perfect season for snorkeling.

Winter

While southern California may not be known for its brutal winters, visiting the park during this time can be a bit tricky.

Choppy waters make it hard for ferries to transport passengers to the islands, and cold rainy days are not uncommon off the coast.

That being said, California winters are unpredictable, and you may get lucky with a few warm sunny days throughout the season.

Always check the weather before heading out and pack plenty of years if you plan on visiting the park in the winter.

Best Things to do in Channel Islands National Park

We suggest planning a minimum of one full day for visiting Channel Islands NP!

Wildlife viewing

Wildlife is one of the main draws to Channel Islands National Park. The islands are home to 20 endemic species that can’t be found anywhere else on earth, including the island fox.

This cute critter is only about as big as a well-fed housecat, but it’s the largest of the islands’ native mammals.

You’re almost guaranteed to spot an island fox if you spend enough time in the park.

Other creatures that are commonly spotted on the Channel Islands include a wide variety of shorebirds, sea lions, seals, whales, and tons of other marine life if you dive beneath the surface.

Junior Ranger Program

The Junior Ranger Program is a great way for visitors of all ages to get an in-depth overview of Channel Islands National Park.

The program is fun and engaging and will teach you all about the park’s flora and fauna, history, and more. Once you complete the Junior Ranger Program, you’ll receive a cool badge to commemorate your time in the park.

Snorkeling/Diving

About half of the park is actually located beneath the surface, so diving is really the only way to get a glimpse of the park in its entirety.

From the colorful fish to the sun-soaked kelp forests, the biodiversity beneath the water is sure to impress. You can book a snorkeling tour, or if you’re an experienced diver, you can set out on your own.

The best places for exploring the underwater areas of the park include Scorpion Anchorage on Santa Cruz Island and the waters around Anacapa and Santa Barbara islands.

Kayaking

Kayaking is by far one of the best things to do in Channel Islands National Park. You’ll likely see some incredible marine life as you paddle, and the craggy island scenery is best viewed from the water.

Unless you’re a pro, you’ll likely want to book a kayaking tour, which provides you with all the gear you’ll need, plus a knowledgeable guide to take you around the islands.

If you’re a confident paddler, you can always just rent or bring your own gear from the mainland, but note that you’ll need to purchase an add-on to your ferry ticket.

The area around Scorpion Anchorage on Santa Cruz island is one of the most popular places for sea kayaking, followed by Frenchy’s Cove on Anacapa Island.

You'll need to be an extremely skilled paddler if you want to kayak anywhere else along the island chain, as weather and conditions are challenging and unpredictable.

Hiking in Channel Islands National Park

Always carry the 10 essentials for outdoor survival when exploring.

If you plan on hiking around Anacapa Island you need to be prepared for the stairs leading up to the island. Once on the island, you will be able to explore the figure-eight-shaped trail system that meanders around the island.

There is no running water on the island so make sure you pack enough water for your trip along with snacks/food.

Cavern Point Loop

- Distance - 1.7 miles

- Trail Difficulty - Easy

- Time Required - 1 hour

- Trailhead - Santa Cruz Island

If you’re short on time, hiking the Cavern Point Loop is a great way to get some stunning vistas in. The trail begins near Scorpion Anchorage on Santa Cruz and leads through the campground and along the exterior of the island. The views along the way are breathtaking, especially if you hike the loop clockwise. Like many of the islands’ trails, there is little shade available along this route, so plan to hike early in the day and layer on the sunscreen!

East Anacapa Island Trail

- Distance - 2.5 miles

- Trail Difficulty - Easy

- Time Required - 1 hour

- Trailhead - Anacapa Island

This is a trail with a great effort to reward ratio. The short and easy hike encircles the entire Anacapa Island and features incredible views from various lookout points, including Pinniped Point, Inspiration Point, and Cathedral Cove. .

As you hike, you’ll likely see lots of wildlife, including shorebirds, sea lions, seals, and maybe even dolphins and whales, depending on the time of year you are visiting.

Elephant Seal Cove Trail

- Distance - 3.3 miles

- Trail Difficulty - Moderate

- Time Required - 2 hours

- Trailhead - Santa Barbara Island

Starting at Landing Cove, this scenic trail stretches through the center of the island before making its way to the opposite coast.

The trail is aptly named, and once you reach Elephant Seal Cove, you’ll likely see tons of seals and other sea creatures chilling along the craggy shoreline.

Scorpion Canyon Loop

- Distance - 4.5 miles

- Trail Difficulty - Moderate

- Time Required - 2 hours

- Trailhead - Santa Cruz Island

If you’re searching for solitude, hiking along the Scorpion Canyon Loop will scratch that itch. This is one of the less popular trails on Santa Cruz, though the views may have you wondering why.

You’ll pass through valleys, ascend cliffs, and likely see some fascinating wildlife along the way including island foxes and bright blue island scrub jay. For the best views, hike this loop clockwise.

Take this route counterclockwise for a trek that’s easier on the knees.

Black Mountain Trail

- Distance - 6 miles

- Trail Difficulty - Moderate

- Time Required - 3 hours

- Trailhead - Santa Rosa Island

This is one of the most challenging treks in the park. The views along the way are spectacular and ever-changing, and you’ll likely encounter wildlife as you hike.

On a clear day, you’ll be able to take in sweeping views of the entire archipelago from the summit. - about 1200 feet above sea level! Avoid this trail on windy days.

Smugglers Cove Trail

- Distance - 7.7 miles

- Trail Difficulty - Moderate

- Time Required - 4 hours

- Trailhead - Santa Cruz Island

This up and down trail takes hikers through the eastern grasslands of Santa Cruz Island.

You’ll likely see at least a few Island Foxes as you meander this moderately difficult trail, in addition to postcard-perfect views across the water before descending down to a pebbly beach littered with abundant tide pools.

There is no shade along this exposed trail, so try to hike it early in the day and bring plenty of sun protection and water along.

Point Bennett Trail

- Distance - 14.5 miles

- Trail Difficulty - Hard

- Time Required - 6 hours

- Trailhead - San Miguel Island

Due to its location along a former Navy bomb testing area, this is the only trail in the park that requires a guide or volunteer to hike.

In addition to incredible coastal views, this route features some seriously gnarly weather, so be prepared for strong winds year-round.

Once you reach Point Bennett, you’ll see and likely hear the roar of rowdy sea lions and seals that make up one of the most densely populated rookeries in the whole world.

How to beat the crowds in Channel Islands National Park?

The best way to beat the crowds at Channel Islands National Park is by avoiding the busy spring break and summer times.

The shoulder seasons of spring and fall are great times to visit if you want some solitude, and the weather and sea conditions are usually decent during these months as well.

Weekends are also fairly busy, even in the shoulder seasons, so plan your trip during the week if possible. You could also forego some of the busier islands like Santa Cruz and Anacapa and check out Miguel and Santa Barbara islands instead.

Where to stay when visiting Channel Islands National Park

There are no National Park Lodges within the park.

There is lodging available nearby in Ventura.

Ventura Beach Marriott - Consider a stay at Ventura Beach Marriott and take advantage of a grocery/convenience store, a garden, and dry cleaning/laundry services. For some rest and relaxation, visit the hot tub. Free Wi-Fi in public areas is available to all guests, along with a bar and a gym.

Comfort Inn & Suites Ventura Beach - Free to-go breakfast, dry cleaning/laundry services, and a fireplace in the lobby are just a few of the amenities provided at Comfort Inn & Suites Ventura Beach. Free in-room Wi-Fi and a 24-hour business center are available to all guests.

Amanzi Hotel, Ascend Hotel Collection - Free to-go breakfast, dry cleaning/laundry services, and a fireplace in the lobby are just a few of the amenities provided at Amanzi Hotel, Ascend Hotel Collection. Free in-room Wi-Fi and a business center are available to all guests.

Crowne Plaza Ventura Beach - look forward to a terrace, dry cleaning/laundry services, and a bar at Crowne Plaza Ventura Beach, an IHG Hotel. This hotel is a great place to bask in the sun with a beachfront location. Stay connected with in-room Wi-Fi (surcharge), and guests can find other amenities such as a business center and a restaurant.

Residence Inn By Marriott Oxnard - free self-serve breakfast, 36 holes of golf, and a free grocery shopping service. Adventurous travelers may like the basketball, volleyball, and cycling at this hotel. Stay connected with free in-room Wi-Fi, and guests can find other amenities such as dry cleaning/laundry services and a fireplace in the lobby.

Click on the map below to see additional vacation rentals and hotels near the Robert J. Lagomarsino Visitor Center.

Channel Islands Camping

Camping is available year-round on all five islands. Each island has its own established campground, and limited backcountry camping is available on Santa Rosa and Santa Cruz islands with a reservation.

Although there are designated campgrounds, conditions are primitive. In addition, you will need to walk/hike a ways to the campgrounds as there is no island transportation and sites are located away from boat landing areas.

Each campground is outfitted with picnic tables and pit toilets, but campers will need to bring in everything else they will need for the duration of their stay - including food, water, and toilet paper.

Campers are required to store all food and trash in animal- and bird-proof containers. National Park Service food storage boxes are provided at campsites, but coolers, plastic Rubbermaid-type boxes or other types of containers with sealing lids may be used as well.

At the Scorpion Ranch campground on Santa Cruz Island, foxes and ravens are capable of opening zippers. To further secure your food and trash, safety pins, twist ties, paper clips, and small carabiners are suggested to help keep zippers closed.

The exception is Water Canyon Campground (Santa Rosa) and Scorpion Canyon Campground (Santa Cruz), which both have potable water available.

Fires are strictly prohibited. Reservations are required for every campground, and transportation to the island must be booked before securing a site.

For a fun adventure check out Escape Campervans. These campervans have built in beds, kitchen area with refrigerators, and more. You can have them fully set up with kitchen supplies, bedding, and other fun extras. They are painted with epic designs you can't miss!

Escape Campervans has offices in Vancouver, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Denver, Chicago, New York, and Orlando

Santa Barbara Island Camping

Landing Cove Campground

.25 mile hike required

10 sites

Anacapa Island Camping

East Islet Campground

.5 mile hike required

7 sites

Santa Cruz Island Camping

Scorpion Canyon Campground

.5 mile hike required

31 sites

Potable water available

Del Norte Campground (backcountry)

3.5 mile hike required

4 sites

Santa Rosa Island Camping

Water Canyon Campground

1.5 mile hike required

15 sites

Potable water available

Backcountry camping

9+ mile hike required

Various sites along the coast

San Miguel Island Camping

Cuyler Harbor Campground

1-mile hike required

9 sites

For a fun adventure check out Escape Campervans. These campervans have built in beds, kitchen area with refrigerators, and more. You can have them fully set up with kitchen supplies, bedding, and other fun extras. They are painted with epic designs you can't miss!

Escape Campervans has offices in Vancouver, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Denver, New York, and Orlando

Travel Tips

Our first tip is to give yourself more than one day to visit the park. We flew into LAX with plans to visit the park for three days with different boat trips. Well, mother nature had a very different plan for us, and out of the three days we were near the park we managed to go on one wildlife cruise around Anacapa Island.

The other days we were in the Los Angeles area our boat tours were canceled due to weather and small craft warnings.

Channel Islands NP Facts

Channel Islands National Park was established by Congress in 1980.

The park consists of five islands: Anacapa, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, San Miguel and Santa Barbara Island

Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary encompasses the area within six nautical miles of the islands.

Every year over 100,000 seals and sea lions breed and haul out on San Miguel Island.

The Channel Islands provide essential nesting and feeding grounds for 99% of seabirds in Southern California.

Painted Cave is one of the largest and deepest sea caves in the world. It gets its name from the lichens and algae decorating the entrance

Parks Near Channel Islands National Park

Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area

Cesar E Chavez National Monument

Castle Mountains National Monument

Check out all of the National Parks in California along with neighboring National Parks in Arizona, Nevada National Parks, and National Parks in Oregon.