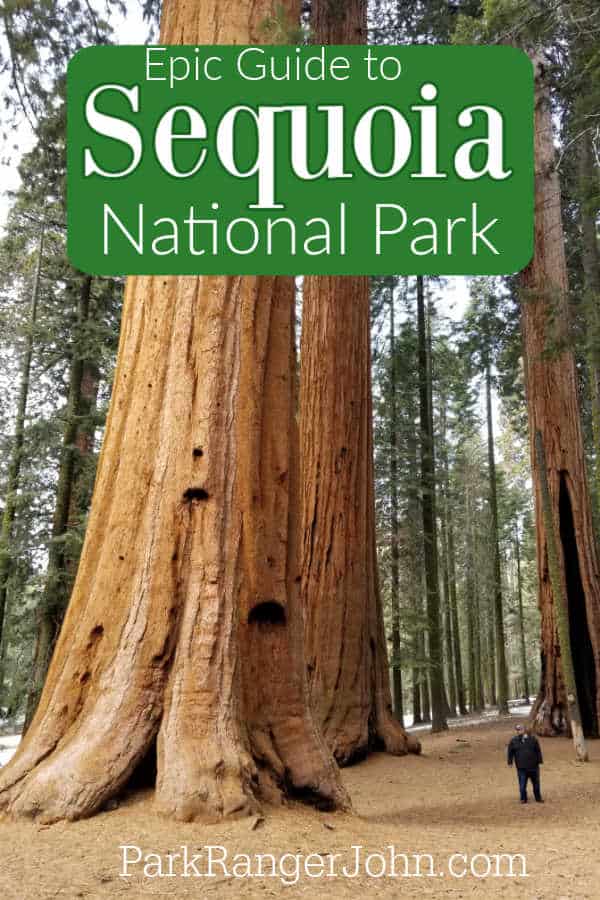

The Epic Guide to Sequoia National Park in California will help you plan and prepare for an unforgettable experience. Here, you find the top things to do, complete camping and lodging guide, epic hiking trails, the history of the park, and so much more.

Sequoia National Park

A trip to Sequoia National Park is a right of passage for anyone who dares to dream big, especially for the National Park enthusiasts out there like myself!

It is a place that will forever change your thoughts and outlook on life as you walk amongst the largest living trees on earth.

You don't believe me? I took my Nephew here when he was 16 and full teenager and there was one word I heard from him all day, "Wow"!

Of course, there were other forms of the word wow like "WOW", "Look WOW", "Whoa, WOW", and "Uncle John, WOW".

There is much more to Sequoia than just large trees. You will also find epic viewpoints, unforgettable hiking like the Moro Rock Trail, caves, and Mount Whitney which is the highest peak in the contiguous United States.

You can also do what is called the Majestic Mountain Loop which is a combination of three National Parks including Sequoia, Kings Canyon, and Yosemite.

So, what’re you waiting for? Keep scrolling to learn more about Sequoia National Park.

About Sequoia National Park

Sequoia National Park is one of the most loved parks in the country.

Sequoia spreads across 404,064 acres in the Sierra Nevada Mountains in central California

Known for its vast forest of towering Sequoia trees (the Giant Forest region within the park is home to five of the top ten largest trees in the world) along with other notable natural destinations, it was visited by 1.2 million people last year!

There are so many things to do including seeing the General Sherman Tree, the largest tree on earth according to volume, Crescent Meadow, Tokopah Falls (1,200 feet tall collection of breathtaking waterfalls), and Tunnel Log (a fallen Sequoia that was cut into to make the road it fell on, accessible again) making a trip to Sequoia delightful for anyone who visits.

Other attractions include Moro Rock, a giant stone dome right by Moro Creek, boasting a stunning view of the park and beyond, and Crystal Cave (a one-of-a-kind marble cavern with an excellent guided tour).

However, it is closed for repairs until 2023 due to the damage incurred by the trail leading to the cave in the Kings Canyon National Park Complex Fire of 2021.

The park shares a boundary with the expansive Inyo National Forest, which is home to Mount Whitney, the highest peak in the contiguous United States, standing tall at 14,505 feet.

Though the mountain isn’t technically located within the park, the peak’s west slope extends into the territory designated as the Sequoia National Park.

One of the most loved parts of the park is the Pacific Crest or John Muir Trail.

Named after John Muir, fondly remembered as the Father of National Parks because of his conservation efforts and influential writings about many regions that went to be protected and preserved, this 211-mile long trail originates in Yosemite, runs through both the Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, before terminating at Mount Whitney.

There are several hikes within the Sequoia National Park region that are worth exploring, depending on your ability and fitness, like the Hazelwood Nature Trail, Crescent Meadow Trail, Tokopah Falls Trail, Alta Peak Trail (believed to be one of the top day-time hikes in the area), and more.

You can also explore the backcountry and camp in the park, go fishing, rock climbing, horseback riding, and even indulge in skiing, snowshoeing, or scenic winter drives if you happen to visit in the thick of the wintertime.

Besides the many scenic overlooks and hikes, the national park is also home to unique animals like the Bighorn Sheep, Coyotes, Black Bears, Cougars, Badgers, etc.

As a Globally Important Bird Area, at Sequoia, you’ll also spot several rare bird species like California Quails, California Spotted Owls, the infamous California Condors, White-headed woodpeckers, etc.

Is Sequoia National Park worth visiting?

Sequoia National Park is one of my absolute favorite National Parks! I have been here numerous times and yet I still get goosebumps walking amongst the Sequoias!

I even sound like a teenager as I drive through the Sequoia Tree and there is nothing like getting out and hugging a massive tree and smelling the forest. You can laugh all you want but I just feel a special connection with these trees!

Even parents with teens will be delightfully surprised by how much they enjoy this park.

Of course, the odds of your teen dropping their phone for the day is about one in a million (This being conservative) you will see them light up as they take Selfies and photos of nature and share them with their friends! This is the perfect place to get them interested in the outdoors and build a bond between you and them.

History of Sequoia National Park

Besides being a diverse landscape with scenic viewpoints and ethereal natural beauty, the region that now encompasses the Sequoia National Park has a vibrant cultural and natural history.

Believed to be home to Native American Settlers ever since 1000 AD, specifically by the Tubatulabal tribes who used to hunt in the area and Monachee Native Americans (evidence of which can still be found in the region) who used to be permanent settlers for the majority of the year except when they used to travel for trade activities.

If you’re intrigued by historical inhabitants and their lives, you’ll find signage and pictographs within Sequoia, like at Hospital Rock, that illustrates and honor the land’s ancestors.

Gradually, the region, much like most of the United States, began to see an influx of European Settlers, the first of whom was Hale Tharp, a miner during the California Gold Rush who built a home within a fallen Sequoia tree (you can still visit Tharp’s Log Cabin while you tour the park today).

The 1860s saw more and more outside settlers exploring the forests of Sequoia while also witnessing a diminishing Native American population that had fallen prey to a host of deadly diseases.

The European Settlers then began to learn the ways of life within the forest, grazing animals on the meadows and conserving the giant Sequoias. John Muir himself visited the region frequently and stayed at the log cabin built by Hale Tharp.

Following several attempts to bring the conservation of the Sequoia trees under the Federal radar, the National Park Service ultimately designated the region as the Giant Forest Park in 1890, causing all mining and logging operations in the area to come to a halt.

Sequoia National Park is the second-oldest park in the country, after Yellowstone National Park, located in Wyoming. It witnessed expansion over several decades after being established as a conservation region, particularly in 1926.

The park also saw the first African American military superintendent, Colonel Charles Young, take charge of the park’s administration in 1903. Following this, the park’s popularity grew multifold, more so after UNESCO declared the region the Sequoia-Kings Canyon Biosphere Reserve in 1976.

Since then, this Southern California National Park has seen more and more visitors every year, each looking for a unique adventure excursion, peace-and-quiet in the forests, or simply a night in the campgrounds under the stars!

Things to know before your visit to Sequoia National Park

Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Park Entrance Fee

Park entrance fees are separate from camping and lodging fees.

Park Entrance Pass - $35.00 Per private vehicle (valid for 1-7 days from the date of purchase)

Park Entrance Pass - Motorcycle - $30.00 Per motorcycle (valid for 1-7 days from the date of purchase)

Per-Person Entrance Pass - $20.00 Visitors 16 years or older who enter on foot, bicycle, or as part of an organized group not involved in a commercial tour.

Annual Park Entrance Pass - $70.00, Admits pass holder and all passengers in a non-commercial vehicle. Valid for one year from the month of purchase.

$20.00 for Non-commercial group (16+ persons)

$45.00-75.00 for commercial sedan with 1-6 seats ($25.00 plus $20.00 per passenger)

$75.00 for commercial van with 7-15 seats

$100.00 commercial Mini-bus with 16-25 seats

$200.00 for commercial Motor Coach with 26+ seats

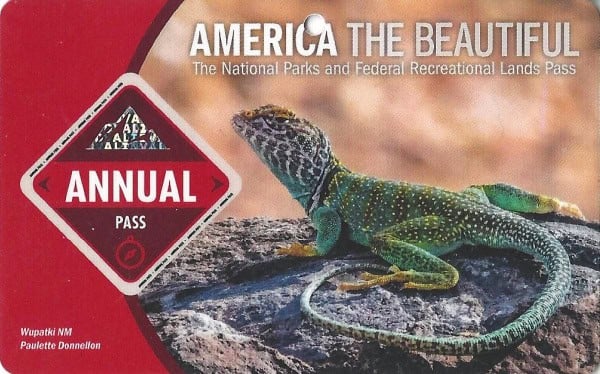

Learn more about National Park Passes for parks that have an entrance fee.

$80.00 - For the America the Beautiful/National Park Pass. The pass covers entrance fees to all US National Park Sites and over 2,000 Federal Recreation Fee Sites for an entire year and covers everyone in the car for per-vehicle sites and up to 4 adults for per-person sites.

Buy your pass at this link, and REI will donate 10% of pass proceeds to the National Forest Foundation, National Park Foundation, and the U.S. Endowment for Forestry & Communities.

National Park Free Entrance Days -Mark your calendars with the five free entrance days the National Park Service offers annually.

Time Zone

Pacific Time Zone

Pets

Pets are permitted in specific areas of the park including parking lots, paved roads, campgrounds, and picnic areas.

Pets are NOT allowed on trails including paved trails. Pets must be on a leash less than 6 feet in length.

Cell Service

Cell service depends on where you are in the park. It is very limited and can be hard to find.

Park Hours

The park is open 24 hours a day year-round. Visitor services hours depend on the time of year.

Wi-Fi

WiFi is available at the Foothills Visitor Center

Parking

You’ll find parking within the park near the most popular destinations, visitor centers, and scenic areas.

It is recommended that you park at the Wolverton or Lodgepole Campground or right by the Giant Forest Museum if you arrive early in the day.

Food/Restaurants

There are several eatery spots within Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Park, some of which are located at the Lodgepole, Cedar Grove, and Grant Grove visitor centers.

The Peaks Restaurant at Wuksachi Lodge

Operational Hours:

Breakfast: 7:00 AM - 10:00 AM

Lunch: 11:30 AM - 3:30 PM

Dinner: 5:00 PM - 8:30 PM

A fine-dining restaurant nestled among the Sequoia National Park, it promises a hearty meal with a killer view!

You’ll find delectable dishes like soups or pan-seared ruby-red trout complemented by a cocktail or wine from the bar.

Open year-round, even during the holidays, for a memorable holiday meal, if you get a chance to dine at The Peaks, you better not miss it!

Lodgepole Café

Operational Hours:

Between 9 AM to 6 PM during the summer months

The ideal spot to get a snack on the go, the Lodgepole Café has been a favorite ever since it opened in 2018.

You’ll find Grilled Chicken Sandwiches, Hot Dogs, Burgers, and several other snacking and dining options.

Wuksachi Pizza Deck

Operational Hours:

Lunch: 11:30 AM - 3:30 PM

Dinner: 5:00 PM - 8:30 PM

A lovely new eatery located on the deck of the Wuksachi Lodge, at the Wuksachi Pizza Deck, you’ll be able to get premium wood-oven pizzas, organic salads, and gourmet sandwiches, accompanied by chilled beer or wine by the glass.

You can also choose to grab a to-go lunch if you want to eat after your hike!

Gas

There are no gas stations within park boundaries, so be sure to fill up your tank before entering. The closest gas stations are in:

- Three Rivers, along Highway 198, 5 miles outside of the Ash Mountain Entrance Station

- Dunlap, along Highway 180, 20 miles west of Grant Grove

Drones

Drones are not permitted within National Park Sites.

Electric Vehicle Charging

While there are no EV charging stations with Sequoia National Park, you’ll find some in Three Rivers, the gateway town to the park. Charging stations are also available in the neighboring towns of Visalia and Fresno.

Don't forget to pack

Don't forget to pack

Insect repellent is always a great idea outdoors, especially around any body of water.

We use Permethrin Spray on our clothes before our park trips. Please read my article on preventing biting insects while enjoying the outdoors.

Sunscreen - I buy environmentally friendly sunscreen whenever possible because you inevitably pull it out at the beach.

Bring your water bottle and plenty of water with you. Plastic water bottles are not sold in the park.

Sunglasses - I always bring sunglasses with me. I personally love Goodr sunglasses because they are lightweight, durable, and have awesome National Park Designs from several National Parks like Joshua Tree, Yellowstone, Hawaii Volcanoes, Acadia, Denali, and more!

Click here to get your National Parks Edition of Goodr Sunglasses!

Binoculars/Spotting Scope - These will help spot birds and wildlife and make them easier to identify. We tend to see waterfowl in the distance, and they are always just a bit too far to identify them without binoculars.

Details about Sequoia National Park

Size - 404,062 acres

Sequoia NP is currently ranked at 22 out of 63 National Parks by Size.

Date Established

The region was established as America’s second national park on September 25, 1890, after the legislation was passed by President Benjamin Harrison.

It went through several expansions, significant ones in 1926 and 1978. The region, along with the Kings Canyon National Park area, was declared the Sequoia-Kings Canyon Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO in 1976.

Visitation

In 2021, Sequoia NP had 1,059,548 park visitors.

In 2020, Sequoia NP had 796,086 park visitors.

In 2019, Sequoia NP had 1,246,053 park visitors.

Learn more about the most visited and least visited National Parks in the US

National Park Address

47050 Generals Highway

Three Rivers, CA 93271

Sequoia National Park Phone Numbers

General Park Info Line (24-hour recording) (559) 565-3341

Lodging Reservations/Cancellations (866) 807-3598

General camping, backpacking, and wilderness information (559) 565-3341

Campground Reservations (877) 444-6777

Cross Country Ski and Snowshoe Information (559) 565-3341

Lost and Found (559) 565-3341

Road and weather information (recorded message) (559) 565-3341

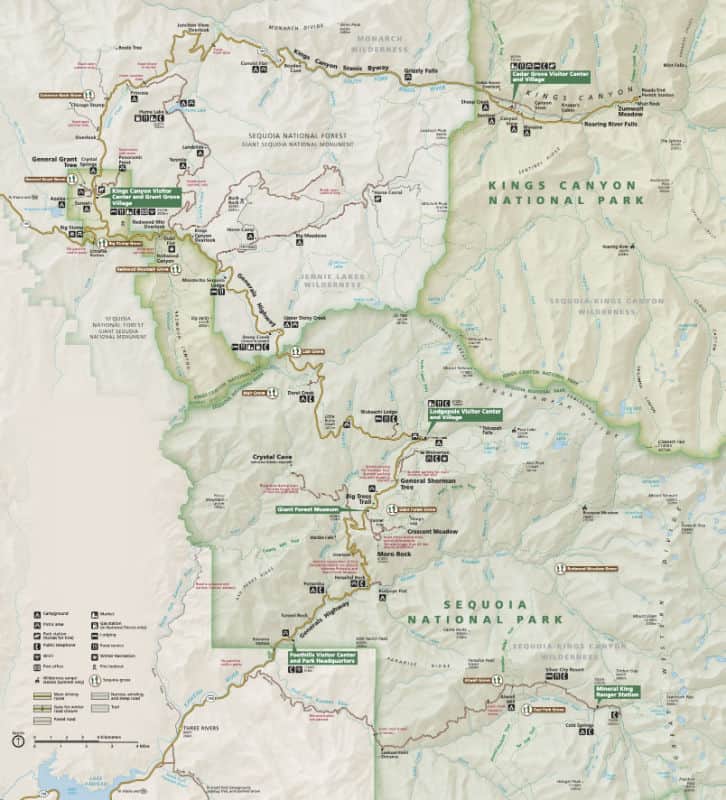

Sequoia National Park Map

For a more detailed map, we really like the National Geographic Trails Illustrated Maps available on Amazon.

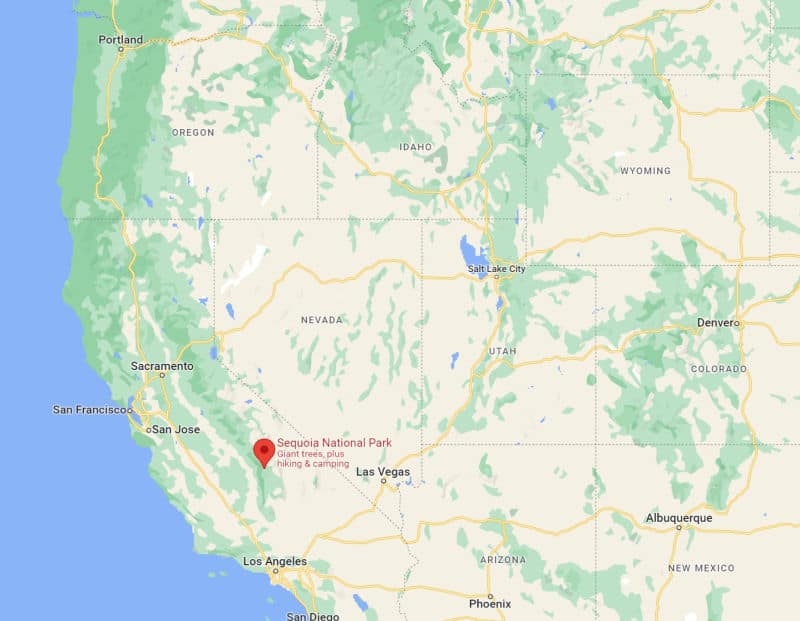

Where is Sequoia National Park?

Sequoia National Park is located in Southern California’s Sierra Nevada Mountain Ranges. Spread across less than half a million acres (404,064 acres), this national park is an oasis of thickly forested regions

(including some of the largest trees in the world, like the General Sherman Tree), cascading waterfalls, excellent trails, vast campgrounds, unique caves, and overlooks like no other!

Estimated distance from major cities nearby

Three Rivers, California - 6 miles

Fresno, California - 58 miles

Modesto, California - 144 miles

Glendale, California - 170 miles

Los Angeles, California - 176 miles

San Jose, California - 181 miles

Fremont, California - 191 miles

Anaheim, California - 194 miles

San Francisco, California - 268 miles

Las Vegas, Nevada - 380 miles

Estimated Distance from nearby National Park

Kings Canyon National Park - 11 miles

Yosemite National Park - 188 miles

Redwood National Park - 567 miles

Pinnacles National Park - 166 miles

Death Valley National Park - 268 miles

Where is the National Park Visitor Center?

Foothills Visitor Center

Operational Hours & Seasons: Open year-round

9:00 AM - 4:00 PM

The Foothills Visitor Center is located near the Ash Mountain Entrance to the park. You’ll find books, gifts, souvenirs, information, interactive exhibits, and ranger-led programs at the visitor center!

The Foothills Visitor Center has exhibits focusing on the Sierra foothills. The most biologically diverse area of the park.

Crystal Cave tour tickets are sold at the Foothills Visitor Center. There is also a small store with books, maps, and Junior Ranger gear for kids. You can rent bear canisters or buy them at the visitor center.

There is an ADA Accessible bathroom near the front entrance.

Giant Forest Museum

Operational Hours & Seasons: Open year-round

9:00 AM to 5:00 PM

Located at an elevation of 6,500 feet, the Giant Forest Museum is home to a collection of interactive exhibits about the beautiful and evergreen Sequoia trees, along with how the environment is ideal for the growth of some of the largest trees in the world and how can we protect it.

Lodgepole Visitor Center

Operational Hours & Seasons: Currently closed for reservations

Otherwise, open seasonally, from mid-May to mid-October

The Lodgepole Visitor Center is situated on an elevation of 6,700 feet and houses several exhibits, an informative park film, information on the cultural and natural history of Sierra Nevada, etc. The visitor center is a part of the area affected by the fires in the region and, as a result, is under renovation until further notice.

The Lodgepole Visitor Center is located on Lodgepole Road just off of the General's Highway approximately 21 miles from the Sequoia NP entrance on Highway 189.

The Lodgepole Visitor Center is two miles north of the General Sherman Tree.

The Lodgepole Visitor Center has a movie that is shown upon request. You can also learn about the natural and human history of the Southern Sierra Nevada Mountains.

Crystal Cave tour tickets are sold at the Lodgepole Visitor Center. You will also find a small store with books, maps and other souvenirs for sale.

Getting to Sequoia National Park

Closest Airports

Fresno Yosemite International Airport - 65 miles

Santa Barbara Municipal Airport - 249 miles

Los Angeles Airport (LAX) - 209 miles

Regional Airports

Woodlake Airport - 22 miles

Visalia Municipal Airport - 40 miles

Portville Municipal Airport - 48 miles

San Luis Obispo County Regional Airport - 174 miles

Driving Directions

On the way to the park keep an eye out for roadside fruit stands. This is a great place to pick up local fruit for your trip! We stop every time we are heading to the park.

From Fresno, California - 77 miles, 1 hour and 20 minutes

You’ll begin your journey to Sequoia National Park by getting on California Route 99 towards Bakersfield and then exiting via Exit 97 onto California Route 198 East.

Ultimately, you’ll continue onto Sierra Drive, leading you to the park’s entrance.

From Glendale, California - 200 miles, three and a half hours

You’ll begin your trip to Sequoia National Park via Interstate 5 North and follow the route for a large part of your drive.

You’ll go on to merge with California 99 North heading towards Bakersfield, and then you’ll take Exit 30 onto California 65 North, heading towards Sequoia National Park.

From Los Angeles, California - 203 miles, 3 hours 45 minutes

You’ll start the drive by getting on US Route 101 N and then get on to Interstate 5 North and follow the route for a while.

You’ll then merge with California 99 North towards Bakersfield and ultimately take Exit 30 onto California 65 North, the road that will take you directly to Sequoia National Park.

From San Jose, California - 230 miles, 4 hours

To get to Sequoia National Park, you’ll have to begin your trip via US Route 101 South before merging with Interstate 5 South for a large part of your trip.

Finally, you’ll take Exit 334 towards California 198 East, which will lead you right to Sequoia National Park.

From Las Vegas, California - 380 miles, 6 hours

To get from Las Vegas to Sequoia National Park, you’ll start on Interstate 515 North.

Then, you’ll continue to Interstate 15 North and progressively take Exit 76A heading towards Los Angeles to switch on to Interstate 15 South, which you’ll follow for most of your ride.

After you enter the Golden State, you’ll get on state routes leading you to the entrance to Sequoia National Park.

Best time to visit Sequoia NP

This really depends on you. If you love the snow and smaller crowds then the winter is amazing in Sequoia. If you are wanting to hit the trails and see the caves I would suggest the summer but you should expect the see crowds.

Weather and Seasons

Spring

With the park coming off of a heavy winter season, you’ll still find snow on the ground. With the wildflowers blooming and the weather becoming more pleasant, it is an excellent time for hikers to visit.

A lovely time to visit while on a weekend getaway, Sequoia National Park in the springtime is bound to be one of the best spots for a peaceful trip!

Summer

Hands-down the peak time for Sequoia National Park as the temperatures rise, the school’s out, and most people come to enjoy the shade of the towering Sequoia trees.

During the summer, all parts of the park are open for exploring. All campgrounds are perfect for spending the night in (especially since August or September is the time when International Dark Sky Festival).

Bonus: You’ll also find the Sequoia Shuttle between the gateway towns of the park.

Fall

With the autumn leaves comes somewhat unpredictable weather, mostly with pleasant days but pretty cold nighttime temperatures.

A couple of the destinations within the park begin to close around this time of year, and you may even start to see snowfall.

However, the fall months always promise a sunset worth going on a strenuous hike for!

Winter

Visiting in the winter isn’t most people’s cup of tea, but if you’re a snow lover and are hoping to have an adventure like no other, there’s no better place to be than at the Sequoia National Park!

With the giant trees clad in pristine white snow, you’ll be able to immerse yourself in winter sports and activities.

Note: Be sure that you take tire chains as the snow can get too thick to drive through sometimes, and stay updated on current weather conditions.

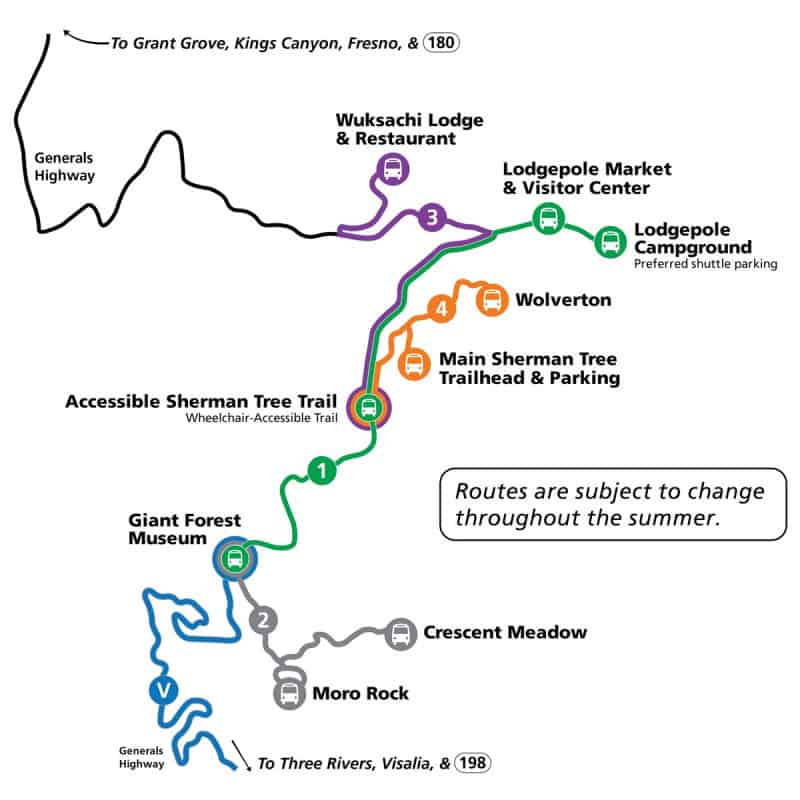

Sequoia Park Shuttles

Sequoia NP has shuttle buses that run between the end of May and mid-September. They are a great way to move around the park and not have to worry about parking.

Giant Forest | Route 1 (Green) | Free

Weekdays: Departs every 12 minutes from 8:00 am to 6:20 pm.

Weekends: Departs every 10 minutes from 8:00 am to 6:20 pm.

- Giant Forest Museum

- General Sherman Tree Accessible Trail

- Lodgepole Market

- Lodgepole Campground

Moro Rock / Crescent Meadow | Route 2 (Gray) | Free

Weekdays: Departs every 12 minutes from 8:30 am to 6:30 pm.

Weekends: Departs every 8 minutes from 8:30 am to 6:00 pm.

Moro Rock-Crescent Meadow Road is closed to private vehicles from 8:00 am to 7:00 pm on weekends once shuttle service begins.

- Giant Forest Museum

- Moro Rock

- Crescent Meadow

Wuksachi Lodge & Restaurant | Route 3 (Purple) | Free

Weekdays: Departs every 30 minutes from 8:00 am to 6:30 pm.

Weekends: Departs every 15 minutes from 8:00 am to 6:30 pm.

- General Sherman Tree Accessible Trail

- Wuksachi Lodge & Restaurant

General Sherman Tree Trails | Route 4 (Orange) | Free

Departs every 15 minutes from 8:00 am to 6:45 pm.

- General Sherman Tree Accessible Trail

- Main General Sherman Tree Trail

- Wolverton Trailhead and Picnic Area

There is also a paid bus that requires reservations that travels from Visalia to Sequoia NP.

Best Things to do in Sequoia National Park

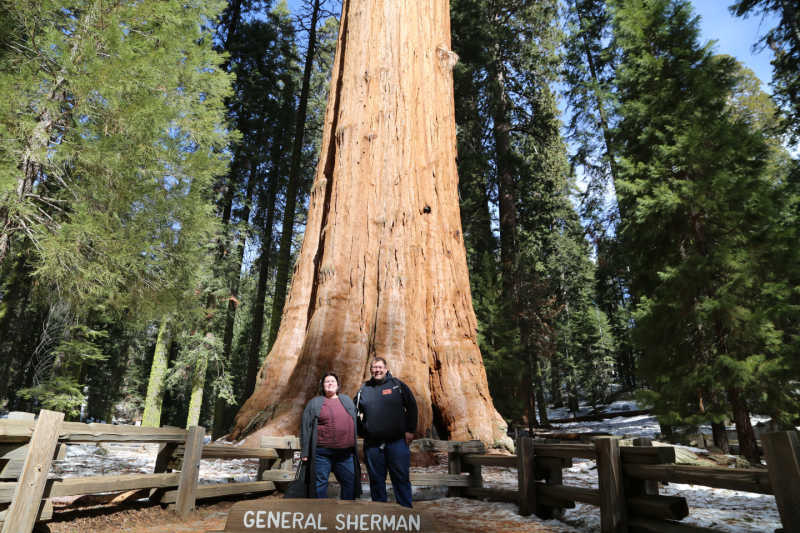

General Sherman Tree

Quite possibly, the crown jewel of the Sequoia National Park is the General Sherman Tree, one of the hundreds of gigantic Sequoia trees in the region.

By volume, the General Sherman Tree is the largest known living tree on earth. It is believed to be 2,500 years old and considered to be a living memorial of the past centuries.

Set at a height of nearly 275 feet and a maximum diameter of 36.5 feet, it is the largest tree by volume and is truly a sight to see.

Crystal Cave

One of the top attractions to see within Sequoia National Park is the Crystal Cave, a marble cavern located between the Ash Mountain Entrance and the Giant Forest region.

Home to a collection of stalactites and stalagmites, this marble cave is worth exploring if you spend a couple of days in the park.

Sign up for a Crystal Cave Tour to see this epic marble cavern

Junior Ranger Program

Numerous ranger-led programs are offered at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, the most popular of which is the Junior Ranger Program, which you can locate at any of the park’s visitor centers.

The parks are also known for their ranged-led talks and guided hikes, including a ranger-led snowshoe walk if you want to explore the scenery in the winter (and can brave the cold)!

The Junior Ranger program for Sequoia National Park and Kings Canyon National Park are combined. There are multiple activities to choose from complete the program. Many of the activities can be done while enjoying lunch or a meal in the park.

You can expect the program to take 30 to 90 minutes depending on the age of the participant. The junior ranger program can be turned in at any of the visitor centers.

Giant Forest Museum

A top destination within the park, the Giant Forest Museum is home to several interactive and informative exhibits about the Sequoia trees, the environment that keeps them alive, human history and contribution, flora and fauna, and other features.

Generals Highway

A long 33-mile road, the General's Highway connects California State Routes 180 and 198 through Sequoia National Park and Forest, the Giant Sequoia National Monument, and the Kings Canyon National Park.

A scenic drive that takes you through some of the thickest forests, it promises stunning views of the Sierra Nevada Mountains and beyond.

Hiking in Sequoia National Park

To best explore the destinations of Sequoia National Park, you must go on some of the many hikes designed by the NPS.

Some of the most recommended trails (based on your ability and strength) are the Moro Rock Trail, the Tokopah Valley Trail, the Congress Trail, and the Watchtower Trail (for sweeping views of Heather Lake), etc.

Remember to carry the ten essentials for outdoor survival and stay well-hydrated when exploring!

Moro Rock

A beautiful granite half-dome structure within the park boundary, Moro Rock promises one of the best overlooks in the entire region.

Though closed in the winter, the granite dome has a long stairway leading visitors to its summit with a challenging but well-worthwhile hike.

How to beat the crowds in Sequoia National Park?

Though the Sequoia National Park sees an average of a million visitors annually, you can time your visit so that you don’t face too many crowds.

The summertime for Sequoia, much like other California or in fact most US National Parks, is the busiest time simply because the weather is ideal, all attractions are open, and more ranger-led programs and guided hikes are offered.

So if you’re looking to avoid the long lines and exhausting waiting times, don’t visit during the summer; instead, opt for a trip in the spring when the wildflowers bloom or the autumn months.

Spending a couple of days in the wintertime is also bound to be serene as not many people enjoy the harsh cold and snowy days.

Additionally, if you’re okay with being an early riser and getting prepared early in the day, traversing around the park’s best spots in the early morning is bound to be an enjoyable experience.

Where to stay when visiting Sequoia National Park

Wuksachi Lodge

Season: Generally open year-round

Located at an elevation of 7,050 feet in the beautiful Giant Forest area of the Sequoia National Park at the Wuksachi Lodge, you’ll be able to choose from one of the hundred rooms available on-site for your stay in the park.

A luxurious top-of-the-line lodge, this property offers panoramic views of the Sequoia trees and towering mountain peaks.

With a perfect blend of an old-timey mountain lodge and contemporary touches, the décor will wow you more than you’d expect.

Though situated in a relatively remote spot of the park, you’ll have all the basic amenities and more available for you on-site.

You’ll be close to several iconic trailheads that you can just roll out of bed and begin your day of exploration with your hot coffee in hand.

Bonus: the lodge is dog-friendly so if you’re traveling with your pet, staying at a fantastic hotel like this is a no-brainer!

Click here to book your stay/learn more about the Wuksachi Lodge.

Lodging near Sequoia NP

Comfort Inn & Suites Sequoia - Take advantage of free to-go breakfast, laundry facilities, and a gym at Comfort Inn & Suites Sequoia/Kings Canyon. For some rest and relaxation, visit the sauna or the steam room. In addition to a hot tub, guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi, with speed of 100+ Mbps (good for 1–2 people or up to 6 devices

Western Holiday Lodge Three Rivers - At Western Holiday Lodge Three Rivers, you can look forward to a playground, laundry facilities, and a fireplace in the lobby. For some rest and relaxation, visit the hot tub. Stay connected with free Wi-Fi in public areas.

Holiday Inn Express Visalia - Take advantage of a free breakfast buffet, golfing on site, and shopping on site at Holiday Inn Express Visalia Sequoia Gateway Area. Free in-room Wi-Fi is available to all guests, along with dry cleaning/laundry services and a business center

Fairfield Inn by Marriott Visalia - Consider a stay at Fairfield Inn by Marriott Visalia Sequoia and take advantage of free continental breakfast, dry cleaning/laundry services, and a business center. For some rest and relaxation, visit the hot tub. Guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi.

Visalia Marriott at the Convention Center - You can look forward to a firepit, a coffee shop/café, and dry cleaning/laundry services at Visalia Marriott at the Convention Center. Active travelers can enjoy aerobics at this hotel. For some rest and relaxation, visit the hot tub. Be sure to enjoy happy hour at the onsite restaurant. Free in-room Wi-Fi is available to all guests, along with a bar and a 24-hour gym.

For additional lodging and vacation rentals near Sequoia NP click on the map below.

Sequoia National Park Camping

Lodgepole Campground

Season: Late March to Late November

Campsites: 214 (Rvs & Trailers permitted, up to 40 feet in length)

Accessibility: Two sites are ADA-accessible, with fully paved walkways for easy wheelchair access

Lodgepole Campground is an expansive area perfect for first-time campers, located on the Marble Fork of the Kaweah River.

Set at an elevation of 6,700 feet, it may witness snowfall in early spring or late fall time. You’ll get ice, firewood, potable water, a dump station, and flush toilets at the campground.

Dorst Creek Campground

Season: mid-June until early September (closed currently)

Campsites: 222 (RVs and Trailers permitted)

Accessibility: Several ADA-accessible sites with fully paved walkways for easy wheelchair access

Situated 6,800 feet above sea level, the Dorst Creek Campground is located in the heart of the national park, close to Muir Grove, Lodgepole Village, and the Giant Forest.

It is considered ideal for touring both the national parks. You’ll get food storage lockers, potable water, and flush toilets at the campground.

Season: Late March to Late September

Campsites: 27 (RVs & Trailers not permitted)

Accessibility: Two sites are ADA-accessible, with fully paved walkways for easy wheelchair access

Located within proximity to the Ash Mountain Entrance to the park, you’ll be camping right by the river, which is bubbling in the spring and summer months.

At the campground, you’ll find potable water and flush toilets, no other amenities.

Potwisha Campground

Season: Open year-round (some sites are reservable, others are given on a first-come, first-serve)

Campsites: 42 (RVs & Trailers permitted, up to 24 feet in length)

Accessibility: Two sites are ADA-accessible, though the campground is on a slope making wheelchair access somewhat difficult

Situated at 2,100 feet right by the Middle Fork of the beautiful Kaweah River, the Potwisha Campground is open year-round, making it the perfect place to camp in the winter as the region doesn’t witness snowfall.

At the campground, you’ll find food storage lockers, potable water, and flush toilets.

South Fork Campground

Season: Open year-round, potable water available between May and October

Campsites: 10 (RVs & Trailers not permitted)

Accessibility: No sites

Probably the most remote campground in the park, this quaint region is nearly an hour’s drive away from most of the park’s top destinations, making it the perfect peaceful getaway.

At this remote campground, you’ll find only food storage lockers and vault toilets.

For a fun adventure check out Escape Campervans. These campervans have built in beds, kitchen area with refrigerators, and more. You can have them fully set up with kitchen supplies, bedding, and other fun extras. They are painted with epic designs you can't miss!

Escape Campervans has offices in Vancouver, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Denver, New York, and Orlando

Travel Tips

These Sequoia National Park Travel Tips are everything we have learned from visiting the park multiple times and reader-submitted tips!

Give yourself time to get to the park. It can be a long drive.

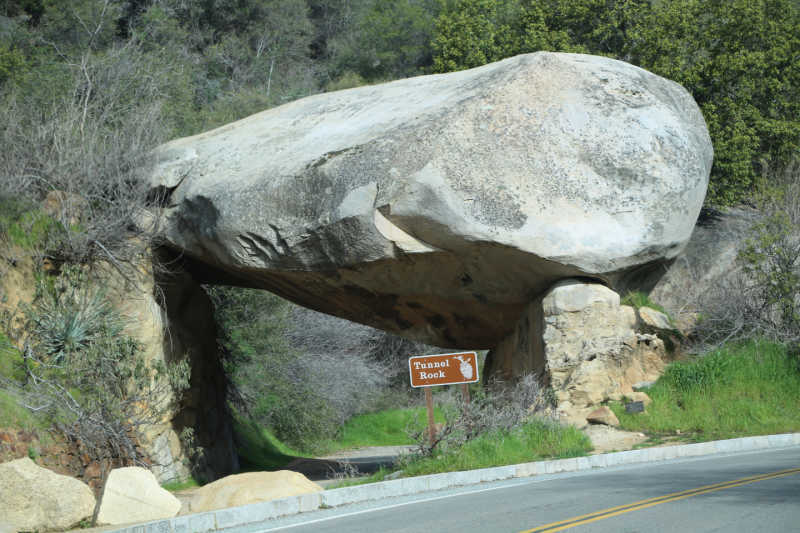

Be prepared for windy curvy roads! It is 16 miles from the main entrance to Giant Grove! The 16 miles include 130 curves and 12 switchbacks! If you or someone you know gets carsick you may want to pack nausea meds or sea-bands.

Pack snacks and water with you for the drive and while you are in the park.

Use the bathroom when you see a bathroom.

Dress in layers and be prepared for weather changes.

Mail a postcard from the post office for a fun family souvenir.

If you plan on doing the Crystal Cave tour make reservations as soon as you know when you will be in the park.

Get gas before you enter the park. There are no gas stations in the park or in Kings Canyon!

Reader Tips for Sequoia NP

My biggest piece of advice is, while you’re there, don’t forget to visit King’s Canyon. It's a highly underrated park, but absolutely breathtaking. Also, while in Sequoia, if you go during fire season, don’t expect great views and anywhere over 8000 ft is going to be chokingly smoky. ~ Scott

Get familiar with the shuttle bus schedule and where stops are. Make sure to get there early ~ Debby

It is a little difficult to get to the General Sherman Tree. I recommend the Grant Grove section of Kings Canyon. ~ Richard

As with visiting any NP.... get up early and hit the hiking trails just before sunrise. ~ Robin

Plan ahead, get up early ~ Melissa

We get up early and usually stay in the park until dark. We are animal watchers. ~ Dallas

Parks Near Sequoia National Park

Manzanar National Historic Site

Devils Postpile National Monument

Point Reyes National Seashore

Fort Point National Historic Site

Rosie the Riveter National Historical Park

Eugene O'Neill National Historic Site

Check out all of the California National Parks along with neighboring Arizona National Parks, Oregon National Parks, and National Parks in Nevada