Epic Guide to Redwood National Park in California! Everything you need to know to plan a great national park vacation, including lodging, camping, things to do, wildlife, and more.

Redwood National Park

The hardest part of exploring Redwood National Park is that you have to wrap your brain around this one principle; you are visiting the Redwoods! Don't get too focused on exploring the traditional National park where you enter a gate and you are just there. Here you will find that When you are visiting Redwood National Park you will most likely also visit

- Jedediah Smith Redwood State Park

- Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park

- Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park

This is largely due to the fact that people were already settled into the redwoods well before areas of land were set aside for a National or State Park. Today, The National Parks Service, along with California State Parks, work together to manage Redwood National Park and the 3 state parks in a unique partnership.

You will not find gates everywhere stating this change, so don't even try. Focus instead on the experience of the Coastal Redwoods and everything this area has to offer.

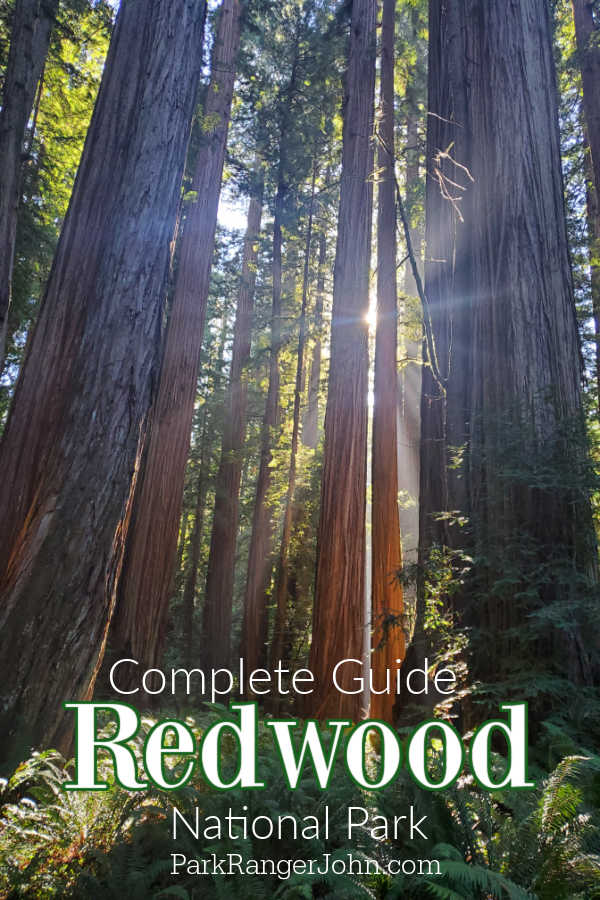

Gazing up at the Redwood Trees is a total National Park Bucket List moment.

Redwood National and State Parks are a UNESCO World Heritage Site and an International Biosphere Reserve.

In 2013, Redwood National Park signed a Sister Park Agreement with Parque National Alerce Costero in Chile. The parks have similar ecologic, historical, and cultural relationships to the lands being managed.

About Redwood Trees

Redwood Trees give a sense of overwhelming immensity that leaves visitors awestruck. They stand proud as their massive trunks soar over 300 feet toward the sky, higher than any other tree on earth.

Their furrowed, auburn trunks are often bare of branches for the first 100 or 200 feet. It appears as if they are reaching towards the clouds far above the forest floor you stand on.

Redwood forests are only found along California's northern coast, in a strip bounded on one side by mountains and on the other by the Pacific Ocean. They are dependent on warm, moist air that stretches nearly 500 miles in length, from Big Sur, south of San Francisco, to just over the Oregon border, and varies in width from 5 to 20 miles, depending on how far the ocean's wet fog fingers creep inland.

Redwood trees have an astonishingly long life span, a millennium or two is not unusual, earning them the nickname "the everlasting."

They have few natural enemies and are stubbornly persistent in the face of adversity. Even when all upper growth is destroyed, the tenacious trees have a backup plan: they clone themselves.

Coast redwoods have a regenerative ability rare in conifers, enabling them to produce sprouts from the many knobby burls that form on the base of mature trees. When a parent tree is cut or damaged, the clones vigorously spring to life.

In just a few weeks, the whole stump is awash with hundreds of hopeful new shoots; those receiving the best light and moisture will form a ring or "family circle" around the parent.

Redwoods reproduce by seed but sprouts grow faster and have a greater chance of survival, for sprouts are not new lives, like seedlings, but the same life in continuation, fed by established roots.

I always laugh that for such a large tree, its cones are surprisingly small, hardly bigger than a human thumbnail. The seeds contained in these cones are minute; an astounding 125,000 of them are needed to make a pound.

Each season, a tree releases millions of seeds, but anywhere from one-half to three-quarters are nonviable, and the remainder face terrible odds. Although winds sometimes carry the lucky ones far afield, most seeds fall within 200 to 400 feet of the parent, not a favorable place to be.

To grow, a seed requires open soil, some sunshine, and adequate moisture, all difficult to obtain beneath the dense canopy of an already established redwood forest.

Even the seeds that land in desirable places must survive still other perils, hungry wildlife, root rot, insufficient rain, sudden cold spells, dry hot winds. The mortality rate is astronomical. Only about one seedling out of a million lives becomes a mature tree.

Once a redwood is tall enough to add its feathery boughs to its canopy, it is almost indestructible and able to protect itself against the dangers that life presents like fire and disease. Remarkably fire-resistant, a redwood will be killed only by the most savage inferno.

It is saved by three things: its heavy layer of insulating bark, often more than a foot thick on a mature tree; the considerable water in the wood itself; and the absence of pitch, the flammable substance that ignites readily in other conifers.

When flames do damage a coast redwood, leaving a hollowed-out or blackened trunk, the tree's cambium, or growth layer, will cover up the wound so completely that all evidence of the fire is gone. If just a fraction of a tree remains intact after a fire, the redwood will not die; instead, it will heal and rejuvenate itself, eventually becoming the flourishing Olympian it once was.

While most other trees are vulnerable to fungus attacks and insect invasions, the coast redwood is not. Its bark and heartwood are well endowed with tannin, an astringent substance that not only gives the tree its rich, red color but also inhibits decay and repels insects: most dislike tannin's bitter taste.

Floods are a more formidable enemy as they attack its most vulnerable spot, the roots. One might imagine these forest skyscrapers to have taproots stretching almost to the center of the earth, but in fact, the world's tallest trees have no taproots at all. Instead, they have shallow root systems that reach only 6 to 10 feet down, though they spread as much as 50 feet across.

Because the whole network lies so close to the surface, floods can erode the soil from beneath the giant's base, leaving the hulking tower precariously perched atop a gaping hole. In such instances, the verdict is nearly always the same, death by windfall.

Most frequently, though, floods have just the opposite effect: instead of washing away soil, they bring new layers, burying the roots under deep mounds.

There are redwoods that go as far back as a time when dinosaurs dominated the animal kingdom. Exactly when the first redwoods became a part of this scene is uncertain, although fossil leaves and cones embedded in ancient rock indicate that the ancestors of today's giant conifers existed at least 160 million years ago.

They began in what may seem to us a very strange place, Greenland. Far too cold for redwoods today, this frigid frontier was, in eons past, a subtropical Eden of river deltas and floodplains.

Three kinds of redwoods survived. Two are native to California, the coast redwood and the sierra redwood (better known as the giant sequoia), which grows along the Sierra Nevada's western slopes. The third species, the dawn redwood, is native to the other side of the world, flourishing in China's remote interior provinces.

Because the two Californians look alike, they are often taken for the same tree. But the differences are many: the coast redwoods are taller; the giant sequoias are wider, with more wood relative to their height, and they are older, outliving their coast relatives by almost 1,000 years.

Compared with its colossal cousins, the dawn redwood is a midget, seldom exceeding a height of 140 feet. Unlike the Californian trees, it is deciduous, scattering its needle-like leaves in amber drifts each fall.

How tall are Redwood Trees?

Redwood trees can reach heights of more than 350 feet tall and up to 26 feet in diameter.

The tallest Redwood is named Hyperion, was discovered in 2006. Hyperion stands a whopping 379.7 feet tall, nearly 6 stories taller than the Statue of Liberty.

How old are Redwood Trees?

A typical redwood lives for 500 to 700 years, although some have been documented at more than 2,000 years old.

How old is the oldest Redwood tree?

The oldest coastal redwood is 2,520 years old

Where do Redwood trees grow?

Coast Redwoods grow along the Northern California Coast and into southernmost Coastal Oregon.

Are there Redwoods in Yosemite?

There are no giant Redwoods found in Yosemite NP, however, there are giant Sequoia Trees found in a few groves including the Mariposa Grove. Both Redwoods and Sequoia Trees are close relatives as both are in the cypress (Cupressaceae) family.

Is Redwood National Park worth visiting?

Yes! I can't emphasize how special it is to stand in a Redwood forest and just go for a hike. These massive giants capture your imagination while putting life back in perspective all at the same time. This is not a hike to rush, it's time to seize the moment!

History of Redwood National Park

The Redwoods were an integral part of life for many native tribes along the California Coast.

The Yurok tribe used redwood to build homes, canoes, furniture, and other objects. The tribes continue to be stewards of the Redwoods.

From the 1830s to the 1860s giant sequoias became famous worldwide. During this time commercial sawmills were built in the San Francisco Bay area and coastal redwood logging became widespread.

Starting in the 1840s there started to be the first calls for conservation of the coastal redwood trees.

In 1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Yosemite Grant Act which protected the Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Big Tree Grove.

This act created the first state-controlled park.

On September 25, 1890, Sequoia National Park was established by President Benjamin Harrison to protect the giant Sequoia Trees from logging.

During the early 1900s, there was still 85 to 90% of the redwood forest that remained unlogged. Unfortunately at the same time technology improved making it easier to cut and process large trees.

Big Basin State Park was created to protect Redwoods and was the first step to protecting old-growth redwood forests.

In 1902, William and Elizabeth Kent purchased Muir Woods to preserve the old-growth redwoods and donated it to the United States in 1908. This forest became Muir Woods National Monument.

In 1916, the National Park Service was created.

In 1917, at the urging of National Park Service director Stephen Mather scientist and naturalist John C Merriam, Henry Fairfield Osborn, and Madison Grant drove to see the northern redwoods and survey the landscape.

After witnessing the devastation to this area from logging they launched a movement to save the redwoods.

Save the Redwoods League was founded in March 1918. They hired Newton B. Drury in 1919 to be the Executive Secretary of the Save the Redwood League.

He would provide leadership and service for the next 58 years. Mr. Drury was instrumental in saving the coast redwood forest.

Also during 1919 National Park Service director Stephen T. Mather recommended the creation of Redwood National Park.

During the early 1920s the Save the Redwoods League poured millions of dollars into buying stands of Redwood trees lining the Redwood Highway.

By the mid-1920s the Save the Redwoods League is focused on four projects to protect the coast redwoods - Bull Creek and the Dyerville Flats, Prairie Creek and the Humboldt Lagoons, Del Norte Coast, and the Mill Creek/Smith River redwoods.

John D. Rockefeller contributed $1 million dollars and pledges an additional $1 million to purchase land.

In 1927 the California State Park system was established thanks to grassroots campaigning by conservation groups.

In 1940 President Franklin D. Roosevelt made Kings Canyon and 450,000 surrounding acres America's 26th national park.

Between 1945 and 1948 the number of coastal sawmills tripled. After World War II there was a building frenzy and the demand for redwood soared.

By the end of the 1950s, only an estimated 10% of the original two million acre redwood forest range remained untouched.

In 1961, Save the Redwoods League, the Sierra Club, and the National Geographic Society revived the idea of a redwood national park.

In 1968, After years of advocacy and hard-fought battles, Redwood National Park was established by Congress.

This act protects 58,000 acres of redwood forest in Humboldt and Del Norte counties.

A decade later, President Jimmy Carter added 48,000 acres to Redwood National Park, in response to concerns about the negative impact of logging activity near park borders.

Today fewer than 5% of the original old-growth redwood forest remains less than 120,000 acres.

There are 382,000 acres of protected redwood forests today from southern Oregon to Central California.

Things to know before your visit to Redwood National Park

Redwood National Park Entrance Fee

Park entrance fees are separate from camping and lodging fees.

Redwood National Park does not charge an entrance fee!

Entrance Fees in Redwood National and State Parks are a little different than many US National Park sites.

Redwood National and State Parks are fee-free with the exception of day-use areas within the Prairie Creek Redwoods, Del Norte Coast Redwoods, and Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Parks.

State park day-use passes and Interagency Federal Passes (Senior, Annual, Access, etc.) are accepted within these three state parks.

Golds Bluff Beach - $8 day-use fee

Fern Canyon is within a day-use area and requires paying a day-use fee of $8 per car, or showing a federal or state pass.

Paid at the California State Park entrance kiosk at the southern end of Gold Bluffs Beach. State and federal passes will be honored.

Jedediah Smith Campground - Day Use - $8

Day-use fee for vehicles parked next to the Smith River. State and federal passes will be honored.

Learn more about National Park Passes for parks that have an entrance fee.

$80.00 - For the America the Beautiful/National Park Pass. The pass covers entrance fees to all US National Park Sites and over 2,000 Federal Recreation Fee Sites for an entire year and covers everyone in the car for per-vehicle sites and up to 4 adults for per-person sites.

Buy your pass at this link, and REI will donate 10% of pass proceeds to the National Forest Foundation, National Park Foundation, and the U.S. Endowment for Forestry & Communities.

National Park Free Entrance Days -Mark your calendars with the five free entrance days the National Park Service offers annually.

Time Zone

PST - Pacific Standard Time

Pets

Leashed pets are allowed in the following areas within the park

Parking Areas: Fern Canyon, Lady Bird Johnson, Tall Trees Trail, and Stout Grove parking lots only. Elk Meadow Day Use Area parking lot.

Scenic View Points: Klamath River Overlook, Redwood Creek Overlook.

Developed Campgrounds: Elk Prairie Campground, Gold Bluffs Beach, Mill Creek Campground, and Jedediah Smith Campground.

Beaches: Freshwater Beach, Gold Bluffs Beach, and Crescent Beach.

Gravel Roads: Cal Barrel Road and Walker Road.

Stop by a visitor center to learn about the BARK Ranger program.

Cell Service

There is very limited cellular coverage across Redwood National and State Parks.

Park Hours

The parks here are always open.

Visitor centers are open from 9 am to 5 pm each day in summer, and from 9 am to 4 pm in autumn to spring.

Wi-Fi

Visitor centers do not have Wi-Fi.

Food/Restaurants

There are no restaurants within the park.

We highly suggest packing snacks and road trip food with you plus bringing a cooler of drinks.

Gas

There are no gas stations within the park. Make sure to fill up when you pass through a local area before heading into the park.

Drones

Drones are not allowed to be flown in National Parks or California State Parks.

Electric Vehicle Charging

EV Charging stations are available in Crescent City, Klamath, Trinidad, and Eureka, California.

Don't forget to pack

Don't forget to pack

Don't forget to pack

Insect repellent is always a great idea outdoors, especially around any body of water.

We use Permethrin Spray on our clothes before our park trips. Please read my article on preventing biting insects while enjoying the outdoors.

Sunscreen - I buy environmentally friendly sunscreen whenever possible because you inevitably pull it out at the beach.

Bring your water bottle and plenty of water with you. Plastic water bottles are not sold in the park.

Sunglasses - I always bring sunglasses with me. I personally love Goodr sunglasses because they are lightweight, durable, and have awesome National Park Designs from several National Parks like Joshua Tree, Yellowstone, Hawaii Volcanoes, Acadia, Denali, and more!

Click here to get your National Parks Edition of Goodr Sunglasses!

Binoculars/Spotting Scope - These will help spot birds and wildlife and make them easier to identify. We tend to see waterfowl in the distance, and they are always just a bit too far to identify them without binoculars.

Details about Redwood National Park

Size - 138,999 acres

Redwood np is currently ranked at 38 out of 63 National Parks by Size.

Acreage does not include submerged lands and public roads.

Federal: 71,715 acres

State: 60,268 acres

Del Norte County: 49,935 acres

Humboldt County: 80,843 acres

Date Established

October 2, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the act that established Redwood National Park.

March 1978, President Jimmy Carter signed into law the addition of 48,000 acres to Redwood National Park.

Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park was established on August 13, 1923

Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park was established on October 26, 1925; Mill Creek acreage was added in June 2002

Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park was established on June 3, 1929

Designated a World Heritage Site on September 2, 1980

Designated an International Biosphere Reserve on June 30, 1983

Visitation

In 2020, Redwood NP had 265,177 park visitors.

In 2019, Redwood NP had 504,722 park visitors.

Learn more about the most visited and least visited National Parks in the US

Redwood National Park Address

Park Headquarters address

1111 Second Street

Crescent City, CA 95531

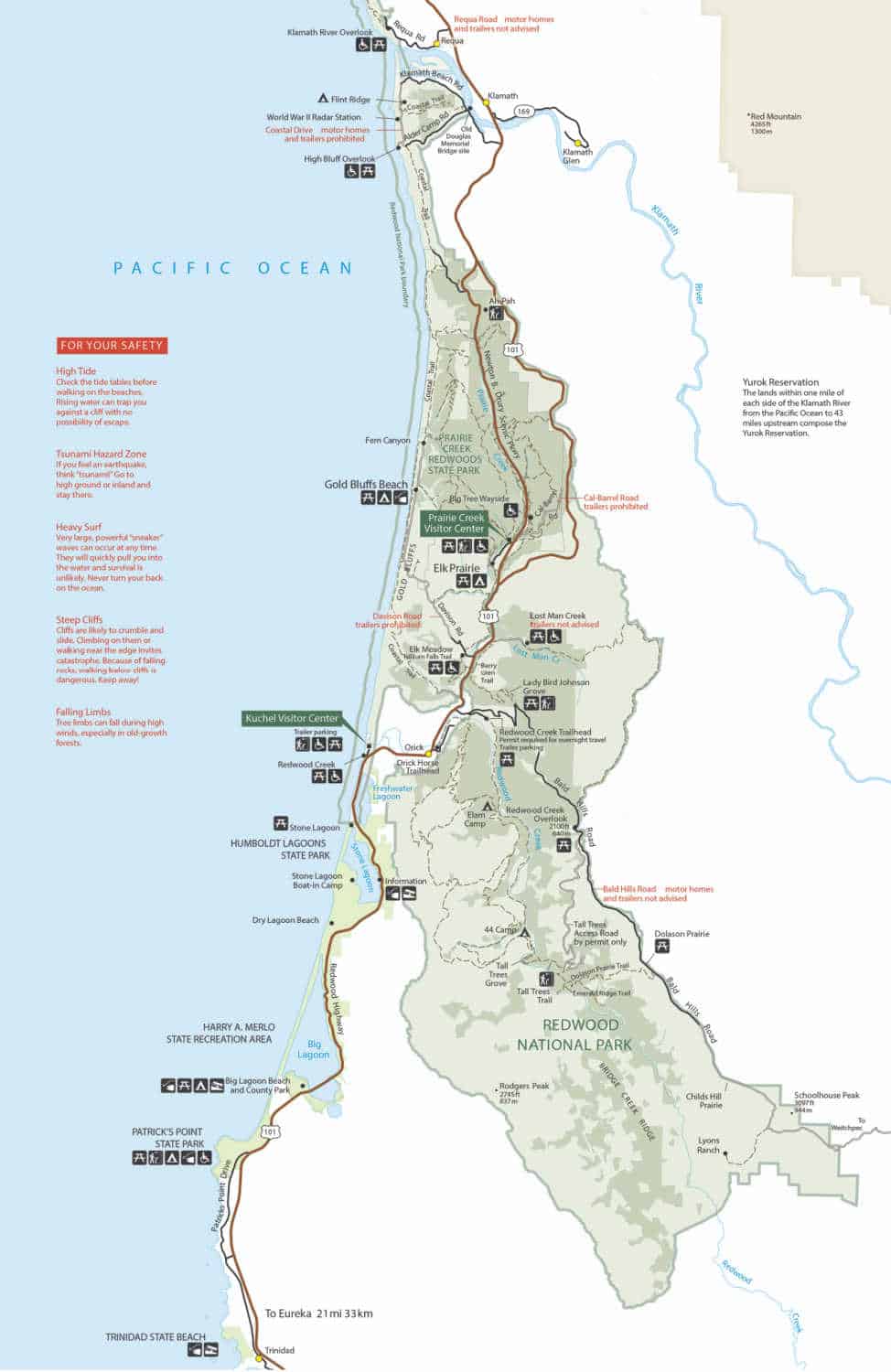

Redwood National Park Map

For a more detailed map, we use the National Geographic Trails Illustrated map available on Amazon.

Credit - National Park Service

Credit - National Park Service

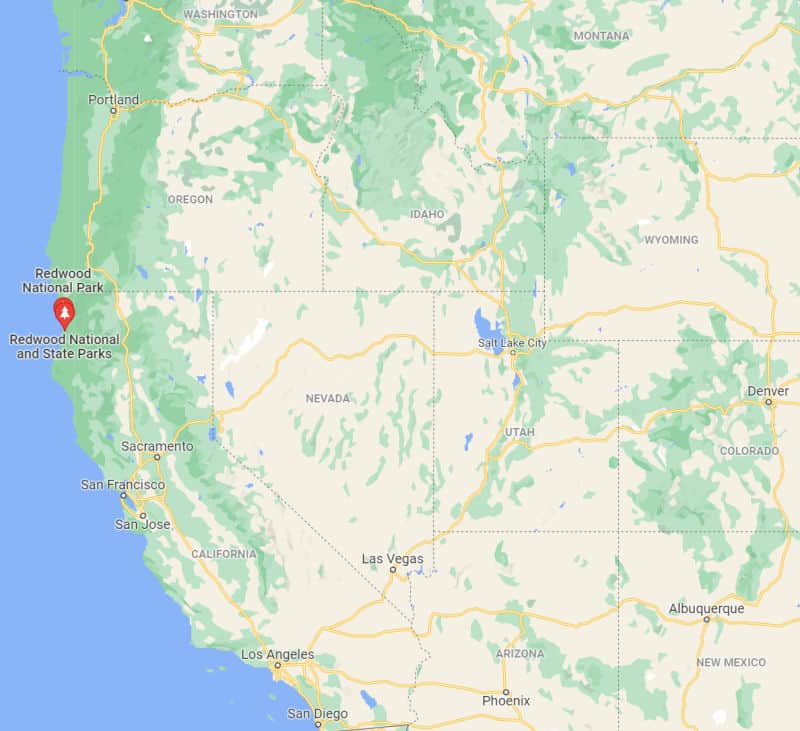

Where is Redwood National Park?

Redwood National and State Parks are located in northernmost coastal California approximately 325 miles (6-hour drive) north of San Francisco.

50 miles long, the parklands stretch from Crescent City, CA (near the Oregon border) in the north to the Redwood Creek watershed south of Orick, CA.

Estimated distance from major cities nearby

San Francisco, CA - 314 miles, 5 hours 40 minutes

Redding, Ca - 171 miles, 3 hours 25 minutes

Portland, Or - 365 miles, 6 hours 30 minutes

Estimated Distance from nearby National Park

Lassen Volcanic National Park - 230 miles from Crescent City, CA, 231 miles from Orick, CA

Crater Lake National Park - 140 miles from Crescent City, CA, 217 miles from Orick, CA

Yosemite National Park - 514 miles from Crescent City, 472 miles from Orick, Ca

Sequoia National Park - 610 miles from Crescent City, 568 miles from Orick, Ca

Kings Canyon National Park - 588 miles from Crescent City, 546 miles from Orick, Ca

Pinnacles National Park - 474 miles from Crescent City, 433 miles from Orick, Ca

Check out all of the best West Coast National Parks!

Where is the National Park Visitor Center?

Thomas H Kuchel Visitor Center

Location - Southern-most visitor center in the parks and located on a beach.

Prairie Creek Visitor Center

Location - Located just off the Newton B. Drury Scenic Parkway - in the heart of Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park.

Hiouchi Visitor Center

Location - Northern-most park visitor center located 9-miles east of Crescent City on Hwy 199.

Crescent City Information Center

Location - Located on the bottom floor of park headquarters.

Jedediah Smith Redwood Visitor Center

Location - Located in the Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park campground.

Getting to Redwood National Park

Closest Airports

California Redwood Coast-Humboldt County Airport (ACV) – 70 miles from Crescent City, 27 miles from Orick, Ca

Del Norte County Regional Airport (CEC) – 3 miles from Crescent City, 45 miles from Orick, Ca

International Airports

Rogue Valley International-Medford Airport (MFR) – 109 miles from Crescent City, 148 miles from Orick, Ca

Sacramento International Airport (SMF) – 365 miles from Crescent City, 323 miles from Orick, Ca

San Francisco International Airport (SFO) – 376 miles from Crescent City, 334 miles from Orick, Ca

Oakland International Airport (OAK) – 369 Miles from Crescent City, 327 miles from Orick, Ca

Bus Service

Redwood Coast Transit (RCT) offers service between and among the communities of Smith River, Crescent City, Gasquet, Klamath, Orick, and Arcata, California.

There are no Redwood Shuttle Buses within the national or state parks

Driving Directions

From the Oregon Coast (Highway 101)

Park headquarters and the Crescent City Information Center are located 26 miles south of Brookings, Ore., off of U.S. 101. To directly access Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park (including the Jedediah Smith Campground, Jedediah Smith Visitor Center, and Hiouchi Visitor Center), travel 16 miles south of Brookings, Ore. on U.S. 101 then exit North Bank Road/Calif. 197 and continue southeast ~7 miles to the junction with U.S. 199 in the heart of Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park.

From Central Oregon (Grants Pass, Ore./Interstate 5 corridor)

From Grants Pass, Ore., take U.S. 199/Redwood Highway and travel ~70 miles southwest to the northeast boundary of the parks near Hiouchi, Calif.; continue west an additional 5 miles on U.S. 199, then south ~4.5 miles on U.S. 101 to Crescent City, Calif. (home to the Crescent City Information Center).

From the California Coast (Highway 101)

The Kuchel Visitor Center near the parks' southern boundary is located ~40 miles north of Eureka, Calif. (or 312 miles north of San Francisco, Calif.) just off of U.S. 101. It is 1-mile south of Orick, located on Freshwater Beach. Look for the brown highway signs for Kuchel Visitor Center / Park Information. Do not rely on online maps to give accurate directions: this visitor center is NOT in the town of Orick.

Continue north on U.S. 101 ~3 miles to access Bald Hills Road or ~7 miles to access the Newton B. Drury Scenic Parkway.

From Central California (Redding, Calif./Interstate 5 corridor)

From Redding, Calif., exit Eureka Way/Calif. 299 and continue west ~140 miles to U.S. 101 near Arcata, Calif. Travel north on U.S. 101 ~30 miles to the Kuchel Visitor Center near the parks' southern boundary. Continue north on U.S. 101 ~3 miles to access Bald Hills Road or ~7 miles to access the Newton B. Drury Scenic Parkway. Do not rely on online maps to give accurate directions: this visitor center is NOT in the town of Orick.

Best time to visit Redwood National Park

I would suggest visiting from Spring through Fall as this is when the weather is best as most of the rain comes between October-April. Services are also limited during the winter months.

On the positive side, especially if you don't mind the rain, this makes a great time to visit. I personally love being in the forest during and after rainfall, everything seems so clean and fresh.

Redwood National Park Weather and Seasons

Redwood State and National Park's weather can change multiple times during the day.

It is not uncommon to start the day with fog and end the day with epic sunshine.

We HIGHLY suggest dressing in layers and being prepared for cool mornings and warm afternoons.

Rain gear, sturdy shoes with non-slip soles, and layers are your best bet for visiting the Redwoods.

From October through April, a high-pressure area sitting atop the North Pacific drives a series of storms onshore, dumping the majority 60-80 inches of annual rain over the region.

The area has semi-consistent temperatures ranging from the mid-40s to low 60s especially along the coast.

Best Things to do in Redwood National Park

The top thing to do in Redwood National and State Parks is to gaze in wonder at the sheer height of the coastal Redwood trees.

After gazing in awe at the Redwoods there are still quite a few things to see, do and enjoy in the park.

Wildlife viewing

Wildlife viewing includes Roosevelt Elk, tide pool creatures, epic bird watching, and so much more.

There are 202 native resident species found in the park.

The Redwoods is a diverse ecosystem including tide pools to Redwood forests and everything in between.

There are multiple endangered and threatened species found within the park eco-system including Marbled Murrelet, Western Snowy Plover, Northern Spotted Owl, Steller Sea Lion, and Fishers.

Approximately 280 species of birds have been recorded within the boundaries of Redwood National and State Parks. Approximately one-third of the country’s various bird species have been recorded within the parks.

There are also 816 species of plants found within the park.

Roosevelt Elk

Roosevelt Elk are the largest subspecies of North American Elk. They are one of the most common mammals seen within Redwood NP.

Prime locations to view Roosevelt Elk:

Elk Prairie - six miles north of Orick, California

Elk Meadow - 3 miles north of Orick, California

Golds Bluff Beach

Bald Hills Road - one mile north of Orick, California

Elk can appear anywhere in the park including on major highways and roads.

Adult male elk weigh up to 1,200 pounds and will guard their harem, especially during mating season. Make sure to never approach elk and give them a lot of space.

Condor Reintroduction

Soon visitors will be able to look to the sky and hopefully see California Condors!

In spring 2022 condors will return to the Redwoods!

In a major effort to restore the California condor population, the National Park Service, Yurok Tribe, National Park Foundation, PG&E, and many others have collaborated to reintroduce condors to traditional Yurok territory in Redwood National Park.

It has been more than a century since California Condors flew among the Redwoods.

Lewis and Clark spotted Condors at the mouth of the Columbia River during their expedition.

Currently, there are condors in Grand Canyon NP, Pinnacles NP, and Zion NP.

Biking in the Redwoods

Bicycles are permitted on all public roadways open to vehicle traffic as well as on designated backcountry bike routes.

There are biker/hiker campsites available at the campgrounds along with two designated backcountry campsites.

Biking trails include the Little Bald Hills Trail, Coastal Trail, Ossagon Trail, Davison Trail, Streelow Creek Trail, and Lost Man Creek Trail.

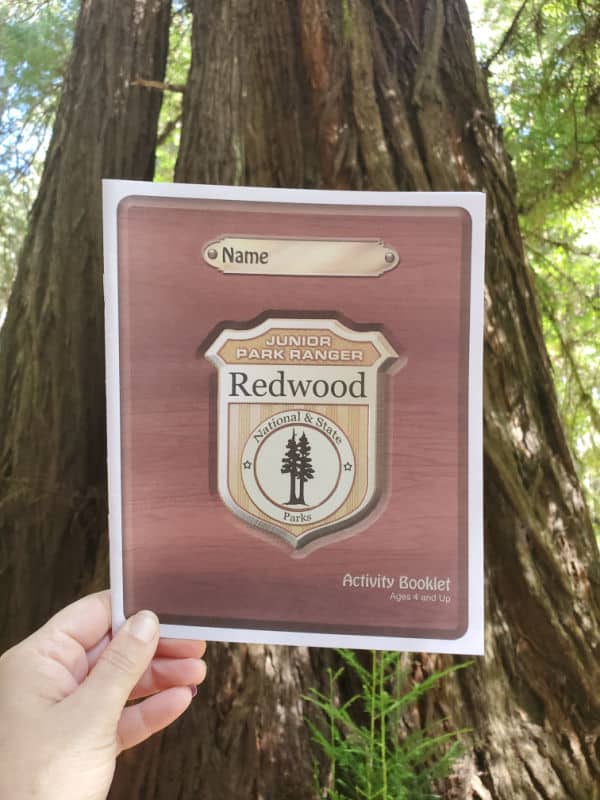

Junior Ranger Program

The Junior Ranger Program can be picked up at the visitor centers. This is a great way for visitors of all ages to learn more about the park.

Redwood NP Junior Ranger activity booklet is available in English, Spanish, Korean, German, Chinese-simplified, Vietnamese, and Russian.

We have done over 125 Junior Ranger programs and learn something new each time we complete one.

The park also offers some fun coloring pages available on the NPS website. These are a great way to get kids excited for your upcoming trip or entertained on the long drive to the park.

Different areas of the park and the surrounding area also have Redwood EdVentures that can be found online or picked up at different visitor centers. These Redwood EdVentures guide you on trails and different areas to find clues.

Once the quest clues are answered you can turn them in for a Redwood Edventure Quest Patch or sticker.

There are more than 20 guests to choose from.

Horseback Riding

Horses and pack animals are welcome on three designated trails within the parks.

Camping is allowed at two stock-ready sites along these trails.

Little Bald Hills Trail

Mill Creek Horse Trail (Day use only)

Orick Horse Trail

Horses are allowed on Crescent, Hidden, and Freshwater Beaches and within Redwood Creek streambed up to the first trail crossing of Redwood Creek.

Where is the drive-thru Redwood Tree?

There is no drive-thru Redwood Trees within the national park or state parks.

There is a couple of drive-through trees near the parks.

Shrine Drive-Thru Tree

Location - Close to Eureka, California

This is the only drive-thru Redwood Tree with a naturally cleaved tunnel.

Klamath Tour Thru Tree

Location - Klamath, Ca - ¼ miles off of US 101

The Tour Thru Tree is approximately 785 years old. The tunnel thru the Redwood tree was completely in May 1976.

The opening is 7 ft 4 inches wide and 9 feet 6 inches high. Standard cars, vans, and pickups may fit.

Chandelier Tree

Location - Legget, California

For more things to do in Redwood NP check out our full list.

Scenic Drives in Redwood National Park

One of the highlights of visiting Redwood State and National Parks is the opportunity to explore the scenic drives.

These scenic drives allow you to fully immerse yourself in a Redwood forest. If you have a sunroof make sure to open it so you can look up at the trees above you (passengers only, drivers should focus in front of the car).

Newton B. Drury Scenic Byway

Location - There are signs leading to the scenic byway off of Highway 101

Distance - 10-mile paved road through the Redwoods

This is a must-see attraction within Redwood NP! The Newton B. Drury Scenic Parkway gives you the opportunity to drive through the heart of an old-growth Redwood forest.

There are multiple trails leading from the parkway, Big Tree wayside, and epic Redwood trees to gaze in wonder at.

Howland Hill Road

Park - Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park

Distance - 10-mile dirt road through the Redwoods

Howland Hill Road is one of my absolute favorite scenic drives in the entire national park system! Here you are going to see massive Redwood trees, streams of light filtering down from the sun onto the dust from the road giving an ethereal feel coming through the trees.

Recreational vehicles, trucks, or vehicles with trailers are too wide for this road.

This dirt road is a couple of miles east of Crescent City. There are numerous pull-outs and trailheads along the road including the Boy Scout Tree Trail and Stout Grove.

This is a great scenic drive. Be prepared for dust and dirt! Your vehicle will not be shiny clean when you are done with this drive.

Bald Hills Road

Location - The exit for Bald Hills Road is 1 mile north of Orick, Ca on Highway 101.

Distance - 17 miles

This county road is not recommended for those driving recreational vehicles, or vehicles pulling trailers.

This drive ascends a steep 15% grade through old-growth redwood trees. There is access to the Lady Bird Johnson and Tall Tree groves.

Hiking in Redwood National Park

There are hundreds of miles of hiking trails within Redwood National and State Parks.

Always carry the 10 essentials for outdoor survival when exploring.

Accessible Trails within the park include the Simpson Reed Grove, Big Tree Trail, Elk Prairie, Foothills/Prairie Creek Loop, Lieffer Loop, and Revelation trail.

Lady Bird Johnson Grove

Park - Redwood NP

Distance - 1.5 mile (2km) loop

Elevation - 121 feet

Difficulty - Easy

Accessibility - This is not ADA accessible. The hiker's bridge to cross the Bald Hills Road exceeds the slope for wheelchairs. The trail itself is composed of aggregate / wood and ranges from four to ten feet wide.

Trailhead - Lady Bird Johnson Grove Trailhead

Parking - RVs, and trailers are not advised. The parking area has limited space and it often is full from summer mornings to late afternoon.

This trail loop winds through an old-growth Redwood forest. Less than 4% of the old-growth redwood forest remains which makes this trail even more special.

Stout Grove Trail

Park - Jedediah Smith Redwood State Park

Distance - .5 mile Loop Trail

Elevation - 75 feet

Difficulty - Easy

Trailhead -East end of Howland Hill Road

Parking - This parking lot is not large. You may need to wait for a space to become available.

This loop trail leads you through colossal redwoods. It is one of our favorite hiking trails in Redwood NP

Prairie Creek and Foothill Loop

Park - Prairie Creek State Park

Distance - 2.5-mile loop

Elevation - 77 foot

Difficulty - Easy

Trailhead - Prairie Creek Visitor Center

Boy Scout Tree Trail

Park - Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park

Distance - 5.5-mile round trip trail

Elevation - 750 feet

Difficulty - Moderate

Trailhead - 3.5 miles East of Elk Valley Road on Howland Hill Road

Parking - Parking at the trailhead may be limited

This trail starts off fantastic as you hike through the Redwood trees. You hike to an open area that really gives perspective to the size of these trees before again hiking amongst these giants. There is a short spur to the Boy Scout Tree, where a doubletree resembles the Boy Scout's two-finger salute. The trail ends at Fern Falls, a nice little waterfall but nothing exciting compared to the Redwoods!

Trillium Falls

Park - Prairie Creek Redwood State Park

Distance - .5 miles each way

Elevation - 200 feet

Difficulty - Moderate

Trailhead - Elk Meadow - just off Davison Road, three miles north of Orick

Parking - plenty of parking for vehicles of any size (busses, RV's, and trailers included).

This is a nice hike amongst Redwoods and a nice waterfall. The trail can be pretty busy as it is right off highway 101.

Fern Canyon Loop Trail

Park - Gold Bluffs Beach, Prairie Creek State Park

Distance - 1-mile "lolly-pop" loop

Elevation - 150 feet

Difficulty - Easy, may need to step over a log or two

Trailhead - Fern Canyon Trailhead

Parking - Davison Road (a dirt road) is not suitable for large recreational vehicles or anything towing a trailer. Low clearance vehicles may get stuck crossing the two streams.

Fern Canyon was featured in Steven Spielberg's movie Jurassic Park 2: The Lost World. Take a nice short hike up the canyon for breathtaking views! For a longer hike, you can take a 5-mile hike on the James Irvine Trail that begins at the Prairie Creek Visitor Center.

Revelation Trail

Park - Prairie Creek State Park

Distance - .3 miles

Elevation - 36 feet

Difficulty - Easy

Trailhead - Located at the Prairie Creek Visitor Center.

Parking - Near the visitor center

The Revelation Trail is approximately 500 yards past the Prairie Creek Visitor Center. It is a fantastic ¼ mile long ADA Accessible loop-trail that is flat and is through some of the most beautiful, and easily accessible old-growth redwoods.

How to beat the crowds in Redwood National Park?

One of the cool things about Redwood National and State Parks is they are pretty spread out. You can easily move around people and explore the park.

We do tend to find congestion getting to Golds Bluff Beach as cars line up to go through the pay booth.

Where to stay when visiting Redwood National Park

There are no National Park Lodges within Redwood State and National Park.

There are 8 basic cabins located within the state park campgrounds.

Jedediah Smith Redwood State Park - 4 cabins

Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park - 4 cabins

When looking for lodging near Redwood NP and State Parks we suggest looking in Crescent City, Orick, Arcata, or Eureka.

Emerald Forest Cabins - smoke-free cabin features a meeting room, laundry facilities, and an arcade/game room. Free Wi-Fi in public areas and free self parking are also provided. Additionally, tour/ticket assistance, a garden, and barbecue grills are onsite. All 21 cabins provide conveniences like washers/dryers and refrigerators, plus free Wi-Fi and microwaves. Coffee makers and free toiletries are among the other amenities available to guests.

Holiday Inn Express Arcata/Eureka - At Holiday Inn Express Arcata / Eureka - Airport Area, an IHG Hotel, you can look forward to a free breakfast buffet, a free roundtrip airport shuttle, and a terrace. For some rest and relaxation, visit the hot tub. In addition to shopping on site and laundry facilities, guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi.

Holiday Inn Express Klamath - Redwood Natl Pk Area - Take advantage of free continental breakfast, a fireplace in the lobby, and a gym at Holiday Inn Express Klamath - Redwood Natl Pk Area, an IHG Hotel. Free in-room Wi-Fi and a business center are available to all guests.

Oceanview Inn in Crescent City - Take advantage of free breakfast, laundry facilities, and a fireplace in the lobby at Oceanview Inn. In addition to a business center, guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi.

Anchor Beach Inn in Crescent City - Anchor Beach Inn provides laundry facilities and more. Stay connected with free in-room Wi-Fi.

Click on the map below to see current rates for hotels and vacation rentals near Redwood NP.

Redwood National Park Camping

Camping in the Redwoods is a dream come true for anyone who loves big trees like the Redwoods in Northern California.

Reservations can be made by calling Reserve California at 1-800-444-7275.

We HIGHLY suggest making a reservation as far out as possible to ensure you have a campsite.

Jedediah Smith Campground

State Park - Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park

Season - year-round

Campsites - 86 tent or RV (no hook-ups); hiker/biker sites available.

Reservations - Yes, Jedediah Smith Campground will be reservable from May 1 - October 1.

Vehicle Length Limits - 25 foot RV or 21-foot trailer is the maximum size in the campground.

Mill Creek Campground

State Park - Del Norte Coast Redwood State Park

Season - Summer months

Campsites - 145 tent or RV (no hook-ups); hiker/biker sites available

Reservations - Yes

Vehicle Length - 28 foot RV or 24 Foot trailer are the maximum size in the campground

Elk Prairie Campground

State Park - Prairie Creek Redwood State Park

Season - year-round

Campsites - 75 tents or RV (no hook-ups); hike/bike sites available

Reservations - Yes

Vehicle Length - 27 foot RV or 24-foot trailer are the maximum size in the campground

Golds Bluff Beach Campground

State Park - Prairie Creek Redwood State Park

Season - year-round

Campsites - 24

Reservations - Yes

Vehicle Size - 24 foot RV, no trailers are allowed in the campground.

Camping near Redwood State and National Park

There are additional campgrounds available in Humboldt County and Del Norte County that are privately owned.

There are also campgrounds in Smith River National Recreation part of Six Rivers National Forest along within Clam Beach County Park and Big Lagoon County Park.

For a fun adventure check out Escape Campervans. These campervans have built in beds, kitchen area with refrigerators, and more. You can have them fully set up with kitchen supplies, bedding, and other fun extras. They are painted with epic designs you can't miss!

Escape Campervans has offices in Vancouver, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Denver, New York, and Orlando

Parks near Redwood National Park

Humboldt Redwoods State Park

Oregon Caves National Monument - 1½ hours from Crescent City, CA, 60 miles; 114 miles from Orick, CA

Whiskeytown National Recreation Area - 4¼ hours from Crescent City, CA, 215 miles; 160 miles from Orick, CA

Lava Beds National Monument - 6 hours from Crescent City, CA; 262 miles from Orick, CA

Check out all of the California National Parks along with neighboring Arizona National Parks, Oregon National Parks, and National Parks in Nevada

National Park Service Website