Epic guide to Lassen Volcanic National Park, including things to do, where to stay, the park’s history, and so much more.

Park Alerts

The Main park road and the Bumpass Hell Trail close seasonally due to the amount of snowfall the area receives each year. Make sure to click here for current park closures.

Continued park closures from the 2021 Dixie Fire

* The Dixie fire impacted approximately 68% of Lassen Volcanic National Park

* Numerous park facilities, structures, and trails were destroyed/damaged.

* Emergence closures continue, some with no timeline for repairs, including:

1. Juniper Lake Road, including the campground

2. Southwest walk-in Campground

3. Warner Valley Road beyond trailhead parking, including the campground and Drakesbad Guest Ranch.

Temporary visitor use limits specific to the use of livestock are in place at the following locations:

1. Pacific Crest Trail from Coral Meadows North to the junction with the Horseoe Lake Trail (Grassy Swale)

2. Pacific Crest Trail South from the Warner Valley Trailhead to Boiling Springs Lake.

3. Trails originating from the Warner Valley Trailhead leading to Devils Kitchen, Drakes Lake, and Dream Lake.

4. Drakesbad Guest Ranch developed area.

5. Warner Valley Road as marked by barricades and signage at the point just North of Warner Valley Campground.

Entering closed areas or accessing damaged facilities prohibited and may result in a citation.

Lassen Volcanic National Park

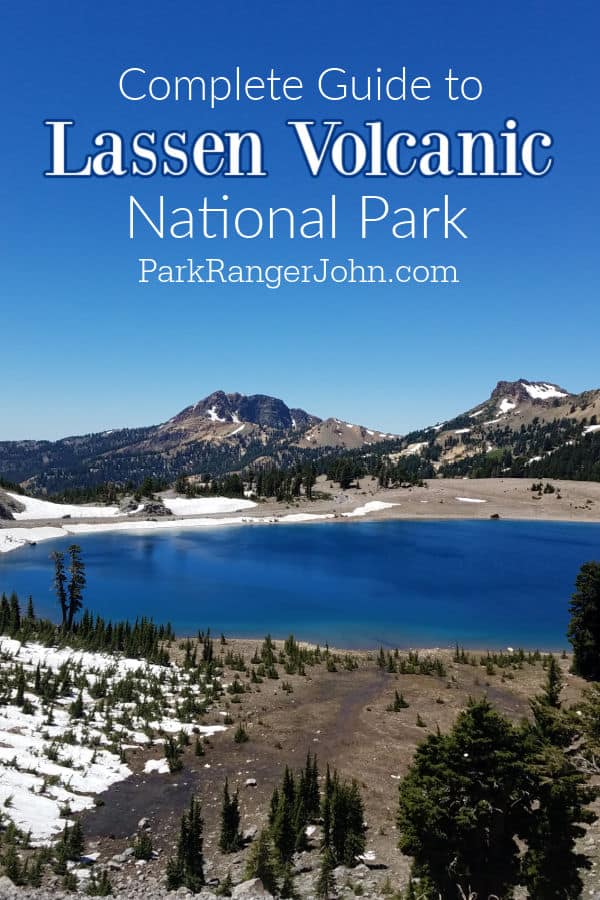

Overflowing with otherworldly landscapes, boiling hot springs, and more than 20 volcanoes, Lassen Volcanic National Park is a unique park that still has yet to break through on the radar of the masses.

Situated in the southernmost region of the Cascade Range in northeastern California, Lassen Volcanic NP is a contradiction of landscapes, with dense forests, barren rocky slopes, glittering alpine lakes, and snowy mountain peaks.

About Lassen Volcanic National Park

The park is one of the only places on earth to play host to all four types of volcanoes, including cinder cones, shield, composite, and plug dome volcanoes.

While you’re here, you can discover the geothermal areas of the park, traverse hundreds of miles of hiking trails, fish or boat along the lakes, snowshoe with a park ranger, and so much more.

Keep reading to discover all there is to see and do at Lassen Volcanic National Park.

It is worth noting that in 2021 the park experienced the Dixie Fire which impacted the east and southeast portions of the park including Warner Valley, Juniper Lake, and portions of the Lassen Volcanic Wilderness.

You will want to be prepared for areas of the park to have burned area hazards including falling trees, loose rocks, unstable shorelines, and signs of the wildfire.

Is Lassen Volcanic National Park worth visiting?

If you’re looking for a piece of untouched wilderness that isn’t completely overrun with tourists, then Lassen Volcanic National Park is absolutely worth exploring.

From vast and diverse landscapes and epic hiking trails to geothermal and volcanic activity, there’s a lot to discover at this northern Californian park.

You might want to check this hidden gem off your bucket list before more people catch on to how great it truly is!

History of Lassen Volcanic National Park

Lassen Volcanic may not be the most known National Park in the system, but it WAS one of the first.

Designated as a national park way back in 1916, LVNP was the 15th national park to join the system of now more than 400 units and counting.

Long before the area was a national park, it was a seasonal hunting ground for numerous native tribes. These peoples remain active in the park today, serving as artifact authenticators, interpreters, naturalists, and fact-checkers.

Lassen Volcanic NP owes its turbulent history to its position astride the Ring of Fire, a chain of about 300 volcanoes that nearly encircles the Pacific Ocean. The volcanoes line the edges of the Pacific Plate, one of the many oddly shaped sections that make up the earth's crust.

As the Pacific Plate grinds against its neighboring plates, the friction produces intense heat deep inside the earth, melting stone into a liquid called magma that works its way up through fissures in the subterranean rock until it bursts forth as lava.

This bursting forth can happen in many ways, depending on the nature of the channel that the magma finds and of the place where it emerges. The remains of many of these volcanic variations are among the outstanding landscape features to be seen at Lassen Volcanic National Park.

Lassen Peak, 10,457 feet in elevation, is quiescent now; perhaps it is resting from its last mighty eruption, which continued from 1914 until 1917. Still, Lassen is only the latest volcanic mountain to reign here. Not long before the Ice Age, it emerged from the northernmost flank of an even more impressive volcano, Mount Tehama.

Much later, Tehama's summit collapsed, leaving a giant pit, or caldera, surrounded by a crown of jagged remains. These remnants, Brokeoff Mountain, Mount Conard, Pilot Pinnacle, Mount Diller, form a steepled circle south of Lassen, like a stony monument to Mount Tehama's past glory.

Just north of Lassen Peak lies Chaos Jumbles, 4½-square-mile rubble of shattered boulders and broken stones partly overgrown by a young evergreen forest. The jumbled mass or rock is the result of explosions that occurred about 300 years ago from Chaos Crags, six volcanic domes near Lassen's northern foot.

Like Lassen itself, they are known as plug-dome volcanoes. A long time ago, solidified magma stopped up their main vents. Pressure from inside the earth mounted until finally the mountains blew up, setting off a series of avalanches that came to rest as Chaos Jumbles.

A different process created Cinder Cone, an 800-foot-high pile of volcanic debris near the park's northeastern border. Since Cinder Cone's vent was not blocked, red-hot lava was able to erupt freely, sometimes sending pillars of fire hundreds of feet high.

During these eruptions, fragments of charred lava fell back around the vent, accumulating as the huge anthill-shaped cone we see today. Finer ash, rising thousands of feet high, was winnowed by the wind and fell in a blanket all around the base of the cone.

These barren deposits, later piled into dunes by winds and weathered by volcanic gases into earthen reds, yellows, and browns, have formed the Painted Dunes.

During the last such eruption, some 200 to 250 years ago, rivers of molten lava also flowed from the vent.

As it cooled, the lava formed low ridges and gave birth to two lakes: Butte Lake and Snag Lake. The bare branches of a drowned forest jut from the water of Snag Lake, the larger of the two.

Things to know before your visit to Lassen Volcanic National Park

Lassen Volcanic National Park Entrance Fee

Park entrance fees are separate from camping and lodging fees.

Park Entrance Pass - $30.00 Per private vehicle (April 16 through November 30) (valid for 1-7 days from the date of purchase)

Park Entrance Pass - $10.00 Per private vehicle (December 1 through April 15) (valid for 1-7 days from the date of purchase)

Park Entrance Pass - Motorcycle/snowmobile - $25.00 Per motorcycle (April 16 through November 30) (valid for 1-7 days from the date of purchase)

Park Entrance Pass - Motorcycle - $10.00 Per motorcycle (December 1 through April 15) (valid for 1-7 days from the date of purchase)

Per-Person Entrance Pass - $15.00 Visitors (April 16 through November 30) 16 years or older who enter on foot, bicycle, or as part of an organized group not involved in a commercial tour.

Per-Person Entrance Pass - $10.00 (December 1 through April 15) Visitors 16 years or older who enter on foot, bicycle, or as part of an organized group not involved in a commercial tour.

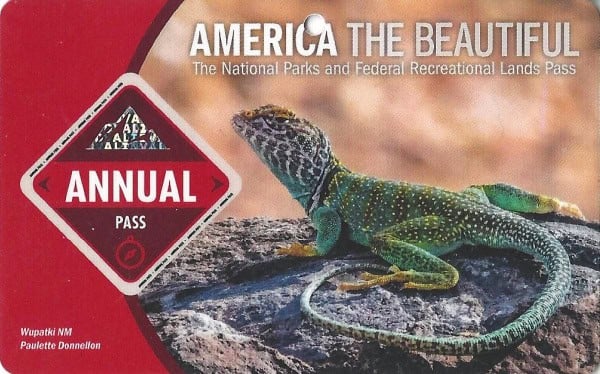

Annual Park Entrance Pass - $55.00, Admits pass holder and all passengers in a non-commercial vehicle. Valid for one year from the month of purchase.

$0.00 Education/Academic Group

$25.00 for commercial sedan with 1-6 seats

$50.00 for commercial van with 7-15 seats

$60.00 for commercial mini-bus with 16-25 seats

$150.00 for commercial motor coach with 26+ seats

Learn more about National Park Passes for parks that have an entrance fee.

$80.00 - For the America the Beautiful/National Park Pass. The pass covers entrance fees to all US National Park Sites and over 2,000 Federal Recreation Fee Sites for an entire year and covers everyone in the car for per-vehicle sites and up to 4 adults for per-person sites.

Buy your pass at this link, and REI will donate 10% of pass proceeds to the National Forest Foundation, National Park Foundation, and the U.S. Endowment for Forestry & Communities.

National Park Free Entrance Days -Mark your calendars with the five free entrance days the National Park Service offers annually.

Time Zone

Pacific Time Zone.

Pets

Pets are allowed in the park as long as they are on a leash six feet or less.

Pets are NOT allowed on any hiking trails, in the backcountry, in any body of water, or inside visitor centers/buildings.

Cell Service

Cell service is limited within the park and varies by area.

Park Hours

The park is open 24 hours a day. The main road access is closed/limited during the winter from approximately November through May.

Wi-Fi

Free Wi-Fi access is available inside the Kohm Yah-mah-nee Visitor Center at the Southwest Entrance of the park.

Don't forget to pack

Insect repellent is always a great idea outdoors, especially around any body of water.

We use Permethrin Spray on our clothes before our park trips. Please read my article on preventing biting insects while enjoying the outdoors.

Sunscreen - I buy environmentally friendly sunscreen whenever possible because you inevitably pull it out at the beach.

Bring your water bottle and plenty of water with you. Plastic water bottles are not sold in the park.

Sunglasses - I always bring sunglasses with me. I personally love Goodr sunglasses because they are lightweight, durable, and have awesome National Park Designs from several National Parks like Joshua Tree, Yellowstone, Hawaii Volcanoes, Acadia, Denali, and more!

Click here to get your National Parks Edition of Goodr Sunglasses!

Binoculars/Spotting Scope - These will help spot birds and wildlife and make them easier to identify. We tend to see waterfowl in the distance, and they are always just a bit too far to identify them without binoculars.

Parking

There is a nice size parking area in front of the visitor centers. Most of the main attractions have fairly good sized parking areas or pull offs.

Food/Restaurants

Lassen Café and Gift Store - Located inside the Kohm Yah-mah-nee Visitor Center year-round.

Manzanita Lake Camper Store - offers food and drinks from mid-May through mid-October

Gas

Unleaded gas is available at the Manzanita Lake Camper store from Mid-May through mid-October.

Drones

Drones are not permitted within National Park Sites.

Electric Vehicle Charging

Two level 2 chargers are available outside of the Kohm Yah-mah-nee Visitor Center near the Southwest Entrance.

If you plan to use these chargers make sure you download the Liberty Hyrdra mobile app and set up an account before your visit.

Details about Lassen Volcanic National Park

Size - 106,589 acres

Lassen Volcanic NP is currently ranked at 40 out of 63 National Parks by Size.

Date Established

August 9, 1916 - The park was established by President Woodrow Wilson. The 17th US National Park created.

Visitation

In 2021, Lassen Volcanic NP had 359,635 park visitors.

In 2020, Lassen Volcanic NP had 542,274 park visitors.

In 2019, Lassen Volcanic NP had 517,039 park visitors.

Learn more about the most visited and least visited National Parks in the US

National Park Address

38050 Highway 36 East

Park Headquarters

Mineral, CA 96063

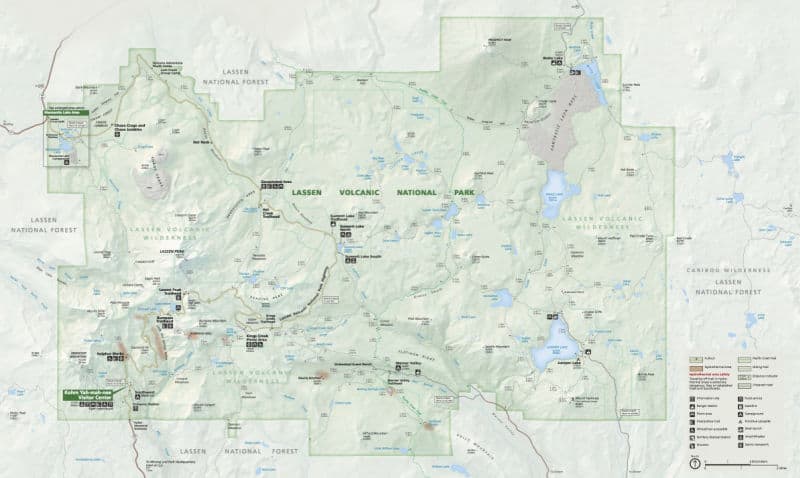

Lassen Volcanic National Park Map

For a more detailed map we like the National Geographic Trails Illustrated Maps available on Amazon.

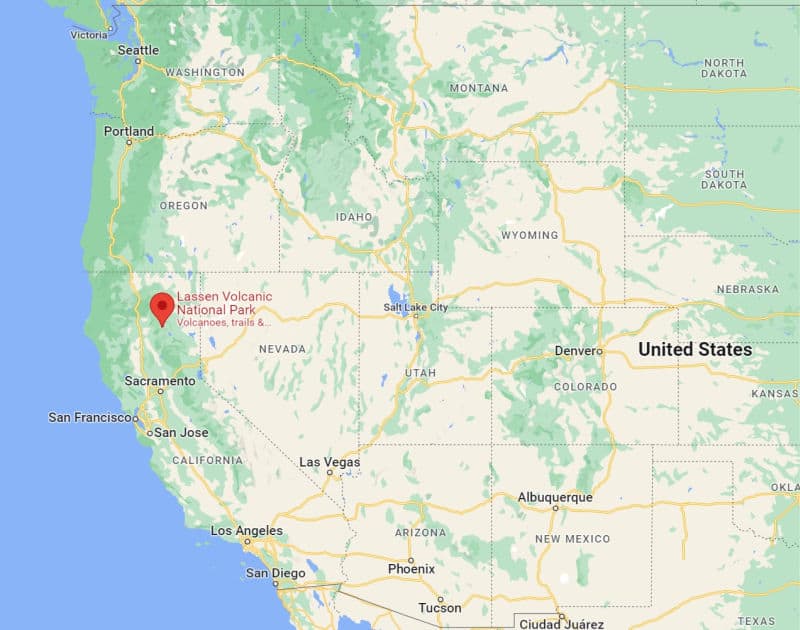

Where is Lassen Volcanic National Park?

Located in northern California, approximately three hours northeast of Sacramento.

Estimated distance from major cities nearby

Chico, CA - 70 miles

Redding, CA - 49 miles

Shasta Lake, CA - 54 miles

Reno, NV - 130 miles

Sacramento, CA - 154 miles

Mineral, CA - 9 miles

San Francisco, CA - 234 miles

Eureka, CA - 194 miles

Crescent City, CA - 258 miles

Estimated Distance from nearby National Park

Redwood National Park - 218 miles

Kings Canyon National Park - 378 miles

Sequoia National Park - 402 miles

Yosemite National Park - 281 miles

Pinnacles National Park - 338 miles

Great Basin National Park - 513 miles

Death Valley National Park - 433 miles

Where is the National Park Visitor Center?

Kohm Yah-mah-nee Visitor Center:

21820 Lassen National Park Highway, Mineral CA 96063

Loomis Museum:

39477 Lassen National Park Highway, Mineral CA 96088

Getting to Lassen Volcanic National Park

Closest Airports

Redding Municipal Airport (RDD)

Sacramento International Airport (SMF)

Reno Tahoe International Airport (RNO)

Oakland International Airport (OAK)

San Francisco International Airport (SFO)

Driving Directions

From Interstate 5 (Redding), take Hwy 44 - 48 miles east to the junction of Hwy 89. Follow Hwy 89 south 1 mile to the north entrance of the park.

From Interstate 5 (Red Bluff) take Hwy 36 E - 51 miles east to the junction of Hwy 89. Follow Hwy 89 north 6 miles to south entrance of the park.

Best time to visit Lassen Volcanic National Park

The best time to visit Lassen Volcanic National Park is between late May and September, as this is when temperatures are at their warmest and most park areas are accessible.

Weather and Seasons

Spring

Spring brings plenty of sunshine to the park, but there’s also still plenty of residual snow leftover from the winter. While the weather is generally pleasant, many areas of the park remain off-limits until at least late spring due to snowfall.

That being said, spring can be a great time to enjoy winter activities like snowshoeing, sledding, and cross-country skiing, among others.

Summer

Summer is the most popular time to visit Lassen Volcanic National Park. Sunny days abound, with temperatures warm in the daytime and cool in the evenings.

This is also the season with the greatest selection of activities and facilities. In addition, the wildflower season is at its peak in the summer months, especially in the higher elevation areas of the park.

Because of the park’s high elevation, some trails are covered with snow through the summer. Most trails are accessible during these months, but be sure to check trail conditions if you plan on hiking.

Fall

Fall is one of the shortest seasons at the park, stretching from October through November.

This is a cool, quiet, and beautiful time of year to visit, though you’ll need to keep an eye on the weather and park closures if there happens to be an early snowfall.

Also, if you visit during the fall, conditions may be hazy or downright smoky due to lightning fires and controlled burns.

Winter

The park remains open year-round, though vehicle access is extremely limited due to hefty snowfall. Some facilities remain open throughout the year, including the Visitor Center and the Southwest Campground.

There are very few visitors in the winter, so you’ll likely have the park mostly to yourself as you snowshoe, cross-country ski, sled, or backcountry ski/snowboard.

If you don’t feel like exploring this winter wonderland all by yourself, there are guided snowshoe hikes available from January through March.

Best Things to do in Lassen Volcanic National Park

We suggest planning a minimum of a full day to explore the park. If you plan to enjoy a few of the great hiking trails and areas away from the heart of the park you will want to plan for a couple of days.

Scenic Highway

The Lassen Volcanic National Highway is a 30-mile scenic route connecting the park's northwest and southwest entrances.

This beautiful stretch passes by dense forests, beautiful lakes, and steep volcanic slopes.

There are no guardrails, and the southern section is especially fear-inducing thanks to the collection of switchbacks and winding roads.

Still, this scenic tour is worth taking - just be sure it’s open during your visit. The highway is usually accessible from June through November, though it all depends on when the snow decides to fall.

Junior Ranger Program

Whether you’re young or young at heart, be sure to partake in the Junior Ranger Program while visiting Lassen Volcanic National Park.

This fun and hands-on program will give you an in-depth look into the park’s geothermal features, wildlife, history, and more. Once you complete the program, you’ll receive a commemorative badge to remember your time at the park.

Sulphur Works

Sulphur Works is the park’s most accessible hydro-thermal area, situated off the main park road.

As you walk along the roadside path, you’ll see steam vents, colorful volcanic rocks, and the main attraction - a bubbling mud pot with an average temperature of 180° Fahrenheit.

You can explore this area by yourself, or go on a ranger-led tour for a more in-depth look at this amazing geothermal feature.

Boating

Lakes abound at Lassen Volcanic National Park, and boating is a great way to experience the water aspects of this incredible area.

Kayaking, paddle boarding, and canoeing are allowed in designated areas, including Manzanita, Summit, Butte, and Juniper lakes.

If you didn’t bring your own flotation device, you can rent single and double kayaks from the Manzanita Lake store from May through September. Note that motorized boats are not allowed anywhere in the park.

Fishing

Lassen Volcanic NP is obviously known for its volcanic activity, but it also has its fair share of abundant fishing holes.

The park is littered with alpine lakes and creeks, and so long as you have a valid California fishing license you can dip your pole into these waters and try your luck for a variety of trout and other species.

Manzanita and Butte lakes are both popular spots to cast out, along with Kings and Grassy Swale creeks.

Ranger Programs

In addition to the Junior Ranger Program, Lassen Volcanic NP offers up an array of fun activities for visitors year-round. Summer has the most abundant offerings, including stargazing, evening chats, and public bird banding demonstrations, among others.

In the winter, there are even guided snowshoe hikes in the southwest area of the park. Some of these programs may be affected due to Covid-19 and fire safety considerations, so check the park website ahead of your visit to see what may be on offer during your trip.

Lassen Volcanic National Park Tours

Hiking in Lassen Volcanic National Park

Always carry the 10 essentials for outdoor survival when exploring.

There are hundreds of miles of trails to traverse at Lassen Volcanic NP. Conditions vary drastically throughout the year due to heavy snowfall and forest fires, so be sure to check out the trail conditions before setting out.

Devastated Area Interpretive Trail

- Distance - .2 miles

- Trail Difficulty - Easy

- Time Required - 10 Min

- Trailhead - Devastate Area parking area

This short, easy interpretive trail depicts the 1914-1916 volcanic eruptions along with views of the Lassen Volcano and its devastated southeast slope.

This is really more of a quick stroll than a full-on hike, but the views and information are definitely worth checking out while you’re in the area.

Manzanita Lake Loop

- Distance - 1.9 miles

- Trail Difficulty - Easy

- Time Required - 1 hour

- Trailhead - Loomis Plaza / Manzanita Lake Day Use Area

Featuring scenic views of Manzanita Lake and the towering Lassen Peak, this easy trail is one of the most popular in the park. There are tons of amenities in the nearby vicinity, including a parking lot, restrooms, a boat launch, and picnicking areas.

Bumpass Hell Trail

- Distance - 2.7 miles

- Trail Difficulty - Easy

- Time Required - 1.5 hours

- Trailhead - Bumpass Hell OR Kings Creek Picnic Trailhead

While the name might be a bit intimidating, Bumpass Hell Trail is actually a pretty easy route, and it winds through one of the most interesting areas of the park. You’ll stroll past remnants of an extinct volcano and a serene lake before coming upon the largest hydrothermal area in the park, complete with sulfery smells and bubbling pools.

Kings Creek Falls Loop

- Distance - 2.3 miles

- Trail Difficulty - Moderate

- Time Required - 2 hours

- Trailhead - Kings Creek Falls Trailhead

Kings Creek Falls Loop winds past Lower Kings Creek Meadow, a marsh crossing, and a log bridge before rewarding hikers with an overlook of the 30-foot Kings Creek Waterfall. This trail is pretty steep in some sections, so hike with caution.

Lassen Peak

- Distance - 5.1 miles

- Trail Difficulty - Hard

- Time Required - 4 hours

- Trailhead - Lassen Peak Trailhead

This is THE hike to do at Lassen Volcanic National Park. It’s longer and harder than most of the other trails, but the views from the top of Lassen Peak are unmatched. You’ll climb through mountain forests and ascend rocky switchbacks before coming to the summit, where you can take in breathtaking panoramic views of the entire park.

How to beat the crowds in Lassen Volcanic National Park?

Even during the busiest months (June through September) at Lassen Volcanic NP, there aren’t a whole lot of crowds to contend with.

This national park is criminally underrated, so those who do decide to visit are blessed with a fairly empty park, no matter the season.

If you truly want the area to yourself, consider visiting during the long winter. If you do visit during the off-season, be prepared for lots of snow - usually upwards of 30 feet per year!

Where to stay when visiting Lassen Volcanic National Park

Drakesbad Guest Ranch

The historic Drakesbad Guest Ranch is located in the secluded Warner Valley of Lassen Volcanic NP.

This is the only hotel-style accommodation in the park, and spots fill up extremely quickly. Reservations are required and can be made up to a year in advance.

Manzanita Lake Camping Cabins

For a luxurious camping experience, check out the Manzanita Lake Camping Cabins.

There are 20 rustic cabins located in the Manzanita Lake Campground, all of which have one room and can sleep between three to eight people. Reservations are required and can be made up to six months in advance.

Lodging near Lassen Volcanic NP

Best Western Rose Quartz Inn - Take advantage of free continental breakfast, an arcade/game room, and a 24-hour gym at Best Western Rose Quartz Inn. For some rest and relaxation, visit the hot tub. Free Wi-Fi in public areas and a business center are available to all guests.

Green Gables Motel & Suites - provides amenities like a garden and laundry facilities. Stay connected with free in-room Wi-Fi.

For additional lodging near Lassen Volcanic NP click on the map below to see current rates for vacation rentals and hotels.

Lassen Volcanic Camping

There are seven campgrounds at Lassen Volcanic National Park, most of which are open seasonally between May/June and September/October depending on snowfall.

Reservations are highly recommended.

No electric hookups are available, though small RVs can be accommodated at certain campgrounds, and there is a dump station at Manzanita Lake Campground.

All sites include a picnic table, a fire ring, and a bear-resistant food storage locker.

Butte Lake Campground

Season: Summer opening dates vary based on spring snow-clearing operations on the park road.

Address:

Butte Lake Campground

Old Station, CA 96071

Campsites: 101 total sites - 6 group sites - 1 equestrian site.

Reservations: Click here to book your stay at Butte Lake Campground.

Reservations are accepted typically from late May through mid-October and can be made a maximum of six months ahead.

Potable water and vault toilets are available seasonally. Reservations are recommended.

Click here for more information on Butte Lake Campground, including photos, campground information, reservation information, and more!

Juniper Lake Campground

Season: Snow Dependant. The campground is usually snow-free by late June.

Address:

Juniper Lake Campground

Chester Juniper Lake Road

Chester, CA 96020

Campsites: 18 total sites - 2 group sites - 1 equestrian site.

Reservations: Click here to book your stay at Juniper Lake Campground

There is no potable water available at Juniper Lake. Sites are first-come-first-served.

Click here for more information on Juniper Lake Campground, including photos, campground information, reservation information, and more!

Lost Creek Group Campground

Season: Campground is closed during late fall through early summer, depending upon snowmelt.

Address:

Lost Creek Campground

Lassen Volcanic National Park Highway

Shingletown, CA 96088

Campsites: 8 group sites.

Reservations: Click here to book your stay at Lost Creek Group Campground.

Potable water and vault toilets are available seasonally. Reservations required.

Manzanita Lake Campground

Season: Summer opening dates vary based on spring snow-clearing operations on the park road.

Address:

Manzanita Lake Campground

Shingletown CA 96088

Campsites: 179 total sites - 5 group sites - 20 rustic cabins.

Reservations: Click here to book your stay at Manzanita Lake Campground. Reservations are required for group sites and cabins. Reservations are recommended for all other sites.

Potable water, flush toilets, vault toilets, showers, dump station, and camp store are available seasonally.

Click here for more information on Manzanita Lake Campground, including photos, campground information, reservation information, and more!

Summit Lake Campgrounds

Summit Lake North

Season: Summer opening dates vary based on spring snow-clearing operations on the park road.

Address:

Summit Lake North Campground

Lassen Peak Highway, Mineral, CA 96063

Campsites: 46 total sites - 1 equestrian site.

Reservations: Click here to book your stay at Summit Lake North Campground.

Potable water, flush toilets, and vault toilets are available seasonally.

Click here for more information on Summit Lake North Campground, including photos, campground information, reservation information, and more!

Summit Lake South

Season: Summer opening dates vary based on spring snow-clearing operations on the park road.

Address:

Summit Lake South Campground

Lassen Peak Highway, Mineral, CA 96063

Campsites: 49 total sites.

Reservations: Click here to book your stay at Summit Lake South Campground.

Potable water and vault toilets are available seasonally. Reservations are recommended.

Click here for more information on Summit Lake South Campground, including photos, campground information, reservation information, and more!

Southwest Campground

Season: Approximately June through October, depending upon weather.

Address:

21820 Lassen National Park Highway

Mineral, CA 96063

Campsites: 21 total sites. Potable water and vault toilets are available year-round.

Reservations: All sites are available on a first-come-first-served basis.

Winter camping is available for self-contained vehicles in the overnight parking area near the visitor center and for tents in the designated over-snow tent camping area.

Click here for more information on Southwest Campground, including photos, campground information, reservation information, and more!

Warner Valley Campground

Season: Summer opening dates vary based on spring snow-clearing operations on the park road. The campground is usually snow-free by June.

Address:

Warner Valley Campground

Chester Warner Valley Rd

Chester, CA 96020

Campsites: 17 total sites.

Reservations: Click here to book your stay at Warner Valley Campground.

Potable water and vault toilets are available seasonally.

Click here for more information on Warner Valley Campground, including photos, campground information, reservation information, and more!

For a fun adventure check out Escape Campervans. These campervans have built in beds, kitchen area with refrigerators, and more. You can have them fully set up with kitchen supplies, bedding, and other fun extras. They are painted with epic designs you can't miss!

Escape Campervans has offices in Vancouver, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Denver, New York, and Orlando

Parks Near Lassen Volcanic National Park

Crater Lake National Park

Redwood National Park

Lava Beds National Monument

Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front National Historical Park

Tule Lake National Monument

Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial

Point Reyes National Seashore

Eugene O'Neill National Historic Site

Check out all of the National Parks in California, along with neighboring National Parks in Arizona, Nevada National Parks, and National Parks in Oregon.