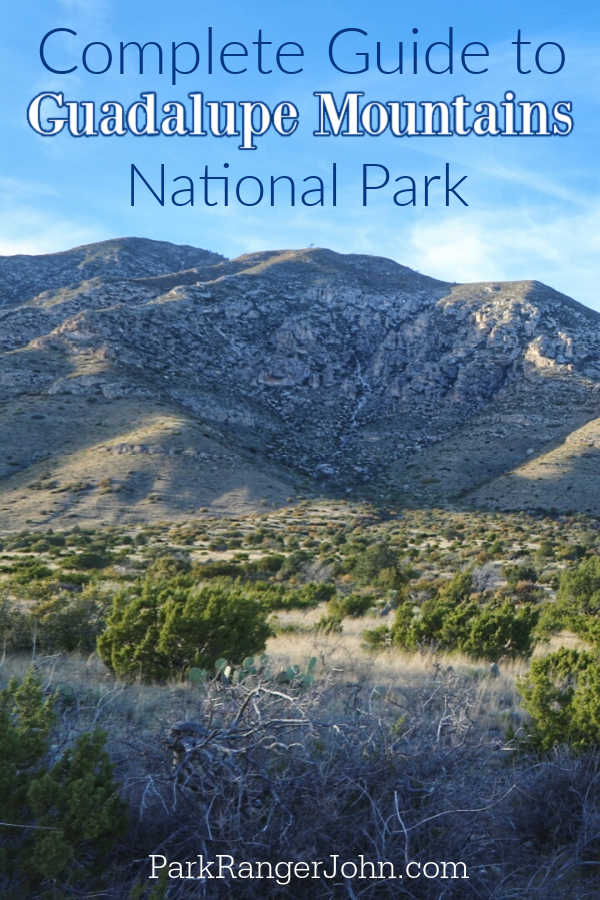

Complete Guide to Guadalupe Mountains National Park in Texas including things to do, camping, lodging, history, hiking, and more.

Guadalupe Mountains National Park

Guadalupe Mountains National Park often flies under the radar, but those who choose to visit this remote area will be rewarded with incredible scenery, thrilling activities, and some of the smallest crowds of any national park in the country.

Below you’ll find the ultimate guide for exploring Guadalupe Mountains National Park, including things to do, when to visit, campground information, and more.

About Guadalupe Mountains National Park

While many drive right by Guadalupe Mountains National Park on their way from El Paso to Carlsbad, those who decide to visit discover a hiking oasis with an incredible backdrop.

The park is the sixth least visited in the nation, mostly due to its remoteness and rugged terrain. This is also what makes the park so stunning, and visitors will be treated to panoramic mountain views, twinkling night skies, and spacious hiking trails - all without the crowds!

Guadalupe Peak is the highest peak in Texas.

Is Guadalupe Mountains National Park worth visiting?

While many don’t make the trek out to remote Far West Texas, Guadalupe Mountains National Park is a hidden gem and absolutely worth visiting!

I highly suggest visiting both Guadalupe Mountains National Park and Carlsbad Caverns National Park on the same trip making it an epic journey to the top of Texas at 8,751 feet in elevation then travel down over 750 feet below the surface at Carlsbad Caverns!

History of Guadalupe Mountains National Park

It is hard to believe that a single gigantic piece of an ocean reef could have become stranded on the dry flats of west Texas; yet here the mountains stand, mile-high remnants of a vanished sea, thrust bodily upward from deep beneath the desert where they had lain buried for longer than 100 million years.

That this forbidding limestone outcrop supports a richly varied community of life is surprising. Yet wildflowers burst from rocky hillsides in springtime like bright pins from a pincushion.

Chipmunks scurry among ferns and pines all summer, and the foliage of aspen, maple, oak, and ash colors the autumn. Deer browse and mountain lions stalk year-round, and an abundance of birds fills the air with song.

The mountain range forms a great V, the arms extending northward into New Mexico (Carlsbad Cavern lies beneath one of them).

Looking southward from the point of the V is the sheer face of El Capitán. At 8,085 feet (more than 2,000 of them straight up), this great ocean-built rock is not the highest mountain in Texas, that title belongs to nearby Guadalupe Peak, but it is certainly the most dramatic.

For more than 50 miles you can see it shimmering in the desert heat, a monolithic landmark guiding travelers to a rich and rugged oasis.

The Capitán Reef

Most of the fossil reef of which the Guadalupe Mountains are a visible part still lies buried thousands of feet deep. Seen on a geologist's map, the reef is a long, almost-complete oval defining the shoreline of a shallow sea that once covered 10,000 square miles of what is now Texas and New Mexico.

That was some 230 to 280 million years ago, long before birds, mammals, or flowering plants had appeared on earth.

The climate was warm and humid. Low hills rimmed the horizon, but otherwise, the land was flat, and water lapped gently along the shore. Lime-secreting algae flourished in the sea, and as they died, their remains were washed shoreward, where they accumulated.

Living algae began to inhabit the limy mass, gluing it together with their own secretions. Other kinds of primitive ocean life lived on the reef, and with the help of minerals precipitated from the water, their bodies were incorporated into its fabric.

With the infinite patience of nature, the structure grew upward and seaward until eventually, it was more than a mile wide and hundreds of feet high, its top just below the water's surface.

The two sides were distinctly different. On the steep seaward side, where waves constantly tore at the reef, great chunks of limestone were broken off; they rolled down the slope into deeper water, creating a layer of rubble, or talus.

On the shore-ward side, where shallow lagoons formed, slow-moving streams deposited sediments, and so the lagoon floor remained almost level with the growing reef.

As the climate changed, the streams dried up and the sea level dropped. The lagoons became stagnant and salty; gypsum, salt, and other sediments built up at a faster and faster rate until they were completely filled in.

Meanwhile, the sea itself had receded, leaving the reef high and dry, no longer alive, its steep slope coated with salt.

After a few million years, the seabed, the lagoons, and the reef between them were all buried beneath a flat plain. And so they remained for more than 100 million years, entombed beneath layers of rock and soil that eventually reached a depth of thousands of feet.

Some 10 to 12 million years ago a great shifting of the earth's surface took place, part of the ongoing process that had begun with the upheaval of the Rocky Mountains.

The basin that had held the ancient sea was tilted and uplifted. The Capitán reef was cracked and fractured in places, and one 40-mile-long piece of it, the part that we call the Guadalupe Mountains, was exposed.

On the southeast, which had been the seaward side, the Guadalupe ridge marks the dividing line between the soft deposits of the seafloor and the harder limestone reef.

On the west, where the reef was sharply broken in the upward thrust, limestone palisades rise almost a mile above broad salt flats.

The Guadalupe Mountains have a long and interesting history.

Humans have roamed this area for more than 10,000 years, starting with the Mescalero Apaches. By the late 1800s, most of these indigenous peoples had been driven out and white settlers attempted to create farms and ranches in the arid landscape. Not surprisingly, few were successful.

The park was officially established in 1972 after a long fight to combine pieces of land and acquire mineral rights. You can learn more about the area’s history at the Frijoles Ranch Museum located in the park.

Things to know before your visit to Guadalupe Mountains National Park

Guadalupe Mountains National Park Entrance Fee

Park entrance fees are separate from camping and lodging fees.

Per-Person Entrance Pass - $10.00 Visitors 16 years or older who enter on foot, bicycle, or as part of an organized group not involved in a commercial tour.

Annual Park Entrance Pass - $35.00, Admits pass holder and all passengers in a non-commercial vehicle. Valid for one year from the month of purchase.

$0.00 for Education/Academic Group

Learn more about National Park Passes for parks that have an entrance fee.

$80.00 - For the America the Beautiful/National Park Pass. The pass covers entrance fees to all US National Park Sites and over 2,000 Federal Recreation Fee Sites for an entire year and covers everyone in the car for per-vehicle sites and up to 4 adults for per-person sites.

Buy your pass at this link, and REI will donate 10% of pass proceeds to the National Forest Foundation, National Park Foundation, and the U.S. Endowment for Forestry & Communities.

National Park Free Entrance Days -Mark your calendars with the five free entrance days the National Park Service offers annually.

Time Zone

MT - Mountain Time

Pets

Pets are allowed at the park, though only in limited areas including areas that are accessible by vehicle and the Pine Springs Campground section of the Pinery Trail connecting the visitor center to the Butterfield Stage Station.

Pets are prohibited in park buildings, restrooms, at public programs, in the backcountry, and on all trails with the exception of the section listed above. This is for your pets' own safety, as there are many natural predators and poisonous plants around the park.

Cell Service

Cell Service is generally available around Pine Springs and Frijole Ranch.

Park Hours

The park is open 24 hours daily all year, though some facilities like the visitor centers and day-use areas have limited hours (generally 8:00 AM-4:30 PM).

Wi-Fi

Free Wi-Fi is available at the Pine Springs Visitor Center.

Parking

Parking is extremely limited at Guadalupe Mountains National Park, so plan to arrive early in the day if you hope to snag a spot. Below we’ve outlined all the parking lots in the park, along with how many spots are available at each.

Dog Canyon Trailhead: 8 total spaces - 1 oversized - 0 accessible

Park here for access to Dog Canyon Trailhead

31.99368140707135, -104.83411431892216

Frijole Ranch: 19 total spaces - 3 oversized - 2 accessible

Park here for access to Frijole Ranch Museum and Smith Springs, Frijole, and Foothill trails.

31.90662, -104.80155

McKittrick Canyon Visitor Center and Trailhead: 40 total spaces - 9 oversized - 4 accessible

Park here for access to the McKittrick Canyon Visitor Center and McKittrick Canyon Trailhead.

31.97728, -104.75208

Pine Springs Trailhead - 24 total spaces - 0 oversized - 2 accessible

Park here for access to Guadalupe Peak, Devil’s Hall, Bowl, and El Capitan trailheads.

31.89650, -104.82819

Pine Springs Visitor Center - 47 total spaces - 12 oversized - 3 accessible

Park here for access to the Pine Springs Visitor Center and the Pinery Nature Trail.

31.89341, -104.82262

Salt Basin Dunes Trailhead - 11 total spaces - 3 oversized - 1 accessible

Park here for access to the Salt Basin Dunes Trailhead.

31.92400, -105.00619

Food/Restaurants

There are no restaurants within the park.

Gas

There are no gas stations within the park.

Drones

Drones are not permitted within National Park Sites.

National Park Passport Stamps

National Park Passport stamps can be found in the visitor center.

We like to use these circle stickers for park stamps so we don't have to bring our passport book with us on every trip.

The National Park Passport Book program is a great way to document all of the parks you have visitied.

You can get Passport Stickers and Annual Stamp Sets to help enhance your Passport Book.

Guadalupe Mountains NP is part of the 1997 Passport Stamp Set

Electric Vehicle Charging

The closest EV Charging Stations are in Van Horn Texas, or in El Paso, Texas

Don't forget to pack

Insect repellent is always a great idea outdoors, especially around any body of water.

We use Permethrin Spray on our clothes before our park trips. Please read my article on preventing biting insects while enjoying the outdoors.

Sunscreen - I buy environmentally friendly sunscreen whenever possible because you inevitably pull it out at the beach.

Bring your water bottle and plenty of water with you. Plastic water bottles are not sold in the park.

Sunglasses - I always bring sunglasses with me. I personally love Goodr sunglasses because they are lightweight, durable, and have awesome National Park Designs from several National Parks like Joshua Tree, Yellowstone, Hawaii Volcanoes, Acadia, Denali, and more!

Click here to get your National Parks Edition of Goodr Sunglasses!

Binoculars/Spotting Scope - These will help spot birds and wildlife and make them easier to identify. We tend to see waterfowl in the distance, and they are always just a bit too far to identify them without binoculars.

Details about Guadalupe Mountains National Park

Size - 86,367 acres

Guadalupe Mountains NP is currently ranked at 42 out of 63 National Parks by Size.

Date Established

Guadalupe Mountains National Park was established in September 1972.

Visitation

In 2021, Guadalupe Mountains NP had 243,291 park visitors.

In 2020, Guadalupe Mountains NP had 151,256 park visitors.

In 2019, Guadalupe Mountains NP had 188,833 park visitors.

Learn more about the most visited and least visited National Parks in the US

National Park Address

400 Pine Canyon

Salt Flat, TX 79847

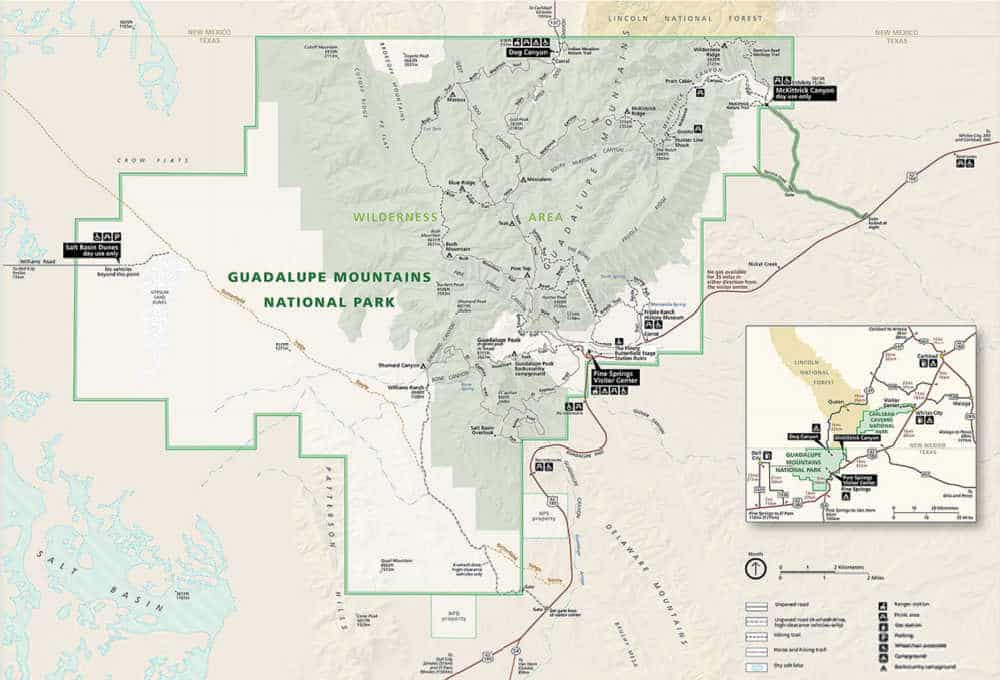

National Park Map

For a more detailed park map we really like the National Geographic Trails Illustrated Maps found on Amazon.

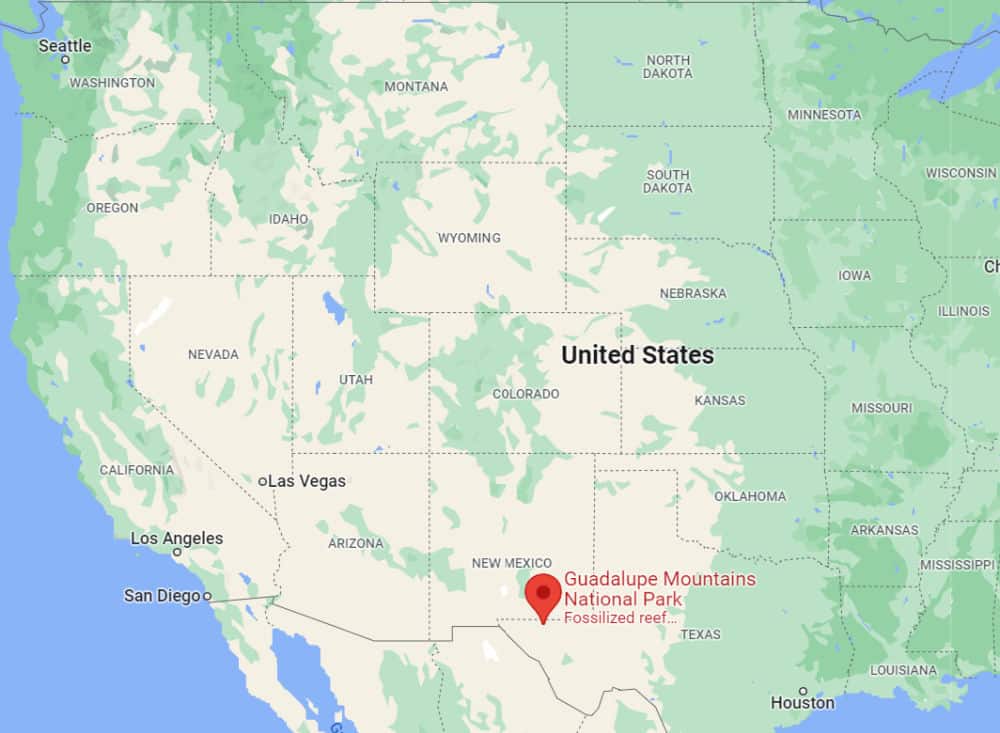

Where is Guadalupe Mountains National Park?

Guadalupe Mountains National Park is located in Far West Texas. The park is far from any big cities, meaning that it is extremely remote.

Because there are no paved roads running through the park, exploring by vehicle is not recommended. Hiking trails are the main routes here, so your own two feet will be your main mode of transportation at Guadalupe Mountains National Park.

Estimated distance from major cities nearby

- El Paso, TX - 113 miles

- Lubbock, TX - 230 miles

- Albuquerque, NM - 333 miles

- Tucson, AZ - 423 miles

- Chandler, AZ - 521 miles

Estimated Distance from nearby National Park

Carlsbad Caverns National Park - 32 miles

White Sands National Park - 192 miles

Big Bend National Park - 235 miles

Saguaro National Park - 415 miles

Petrified Forest National Park - 471 miles

Grand Canyon National Park - 670 miles

Where is the National Park Visitor Center?

Pine Springs Visitor Center

Pipe Springs Visitor Center is the main visitor center for the park. There is a museum, park store, and rangers available to answer questions.

GPS - 31.89341, -104.82262

McKittrick Canyon Visitor Center

McKittrick Canyon Visitor Center is located at the mouth of McKittrick Canyon and staffed during peak seasons including spring and fall.

GPS - 31.97728, -104.75208

Getting to Guadalupe Mountains National Park

Closest Airports

- Carlsbad Cavern Airpark

International Airports

- El Paso International Airport (ELP)

- Albuquerque International Sunport (ABQ)

- Las Cruces International Airport (LRU)

Regional Airports

- Cavern City Air Terminal (CNM)

- Lea County Regional Airport (HOB)

- Roswell International Air Center (ROW)

- Culberson County Airport (VHN)

Driving Directions

Guadalupe Mountains National Park is located on the north side of US Hwy 62/180.

From El Paso, TX, we are 110 miles East of the city. Follow US Hwy 62/180 North to the Pine Springs Visitor Center.

From Van Horn, TX - travel north on US 54 and make a left-hand turn at the junction of US 62/180 to arrive at the park.

From Carlsbad, NM - travel on US Hwy 62/180 South and cross into Texas. Follow signs to the park.

Best time to visit Guadalupe Mountains National Park

The weather inside the park changes drastically with each season, meaning that some months are better for visiting than others. Spring and Fall are the best times to visit, as temperatures are mild during these months. Keep in mind that elevation can have an effect on temperatures, and some areas of the park can be up to ten degrees cooler than the park floor.

Weather and Seasons

Spring

Spring is one of the best times to visit the park. The mild temperatures create the perfect conditions for hiking and backpacking, though it is not uncommon for rain to be in the forecast during these months as well. Spring is usually the busiest month in the park, especially around Spring Break, so try to visit during the week if you’re hoping to avoid the crowds.

Summer

Summertime temperatures at Guadalupe Mountains National Park can reach into the 90s. As most people come to the park to hike, temps this high can be dangerous, especially because there is little shade available on the trails. If you do visit during the summer, be sure to drink plenty of water to avoid heat exhaustion and bring multiple forms of sun protection like hats, sunblock, and long, breathable clothing.

Autumn/Fall

Autumn is another great time to visit the park. While you may not think that a desert would offer much in the way of fall foliage, McKittrick Canyon is in full bloom with vibrant flora during these months. Temperatures are also mild, though rain and high winds are not uncommon during the spring.

Winter

Because of its high altitude, it is not uncommon for snow and freezing fog to appear in the park during the winter. However, highs are typically in the 50s, so check the weather forecast and don’t hesitate to visit if temperatures are bearable.

Best Things to do in Guadalupe Mountains National Park

Because of the park’s remote location and the ruggedness of the roads within the area, it’s important to plan out your trip ahead of time.

The park offers great hiking trails, horseback riding, wildlife and bird watching, and so much more.

Below we’ve outlined some of the best things to do in Guadalupe Mountains National Park.

The Frijoles Ranch

If you’d like to learn more about the history of the area while visiting the park, do not miss the Frijoles Ranch. Also known as the Guadalupe Ranch, this building dates back to the late 1800s, and today it acts as a history museum. Frijoles Ranch houses an impressive collection of artifacts, and the history of the building itself has landed the ranch on the National Register of Historic Places. The museum is located at the end of the Frijoles Ranch Access Road off of US 62.

Salt Basin Dunes

While these scenic dunes are a bit far off the beaten path (about an hour away from the Pine Springs area), you should definitely check them out if you have the time.

After the scenic drive to the trailhead, you’ll need to hike another 1.5-2 hours to get to the gypsum dune, so plan accordingly. Those who make the trek will be rewarded with incredible photo ops of the white dunes against the dark mountainous backdrop, a landscape unlike any other area of the park. Visit a few hours before sunset for the best lighting.

Scenic Drives

Although there are no major roads running through the park, there are some seriously scenic drives along the perimeter. The aforementioned Salt Basin Dunes are one of the most scenic areas in the park, and the drive to this area will give you epic views of El Capitan and the western edge of the Guadalupe Mountains.

You could also take a drive north along Highway 54 for more dramatic views of the mountain range or coast along Highway 62/180 to see the park from the north, south, and west.

Those with 4 wheel drive can make the journey to Williams Ranch, located off of a remote road that will lead you to the western escarpment of the Guadalupe Mountains.

Wildlife Viewing & Bird Watching

Guadalupe Mountains rise sharply from the surrounding Chihuahuan Desert floor which creates the perfect environment for wildlife.

Multiple ecosystems can be found in the park ranging from the harsh desert environment to oak and maple woodlands, rocky canyons, and mountaintop areas filled with ponderosa pine and Douglas firs.

These habitats protect 60 mammal species, 55 reptiles, and 289 bird species.

Because the park is so remote, it plays host to a large variety of wildlife, including mountain lions, wild boar (javelinas), elk, mule deer, jackrabbits, cougars, venomous snakes, scorpions, black bears, and more.

These critters are nocturnal, which makes them extremely elusive.

Your best bet for wildlife watching will happen late at night or early in the morning, though some of these creatures you would be lucky to avoid altogether!

There are over 275 species of birds in the park at any given time, though the types you’ll be able to see depend on the season.

There is a diverse mix of flora and fauna found in the park!

Junior Ranger Program

If you’re traveling with the kiddos, be sure to sign them up for a junior ranger program while visiting the park. Not only is it a fun and interactive way to learn more about the area, but they’ll also receive a cool badge to commemorate their visit once they complete the program.

Fall Colors

A desert may be an unassuming place to see fall colors, but Guadalupe Mountains National Park defies all expectations. McKittrick Canyon bursts into vibrant reds, oranges, and yellow during October and November. This beautiful color show draws visitors from all over, so plan your visit during the week if you want to avoid the crowds.

Horseback Riding

60% of the trails within the park are open to stock use. You must bring your own horse or stock to the park there are no stock rentals available.

The park has stock corrals at Dog Canyon and Frijole Ranch. These corrals have 4 pens and can accommodate up to 10 animals.

A backcountry use permit is required for all stock use. These free permits are issued at the Pine Springs Visitor Center.

Hiking in Guadalupe Mountains National Park

Always carry the 10 essentials for outdoor survival when exploring.

Hiking is one of the main draws to Guadalupe Mountains National Park, and you’ll mostly find trails for more experienced hikers here, including the highest point in all of Texas! Below we’ve outlined some of the very best trails in the park.

Keep in mind that there is very little shade along the trails, so bring plenty of water and sun protection (especially if you are hiking in the summer). Elevation change can also drastically change how warm or cool it feels, so be sure to dress in layers.

Smith Spring Trail - Moderate - 2.4 miles - Loop

McKittrick Canyon Trail - Moderate - 20.2 miles - Out & Back

El Capitan Trail - Moderate - 9.6 miles - Out & Back

Devil’s Hall Trail - Hard - 3.6 miles - Out & Back

The Bowl & Hunter Peak via Frijole and Bear Canyon Trails - Hard - 8.4 miles - Loop

Guadalupe Peak Texas Highpoint Trail - Hard - 8.4 miles - Out & Back

How to beat the crowds in Guadalupe Mountains National Park?

Because of its remote location, crowds are rarely present at Guadalupe Mountain National Park. In fact, this is one of the least visited parks in the entire country.

That being said, spring (specifically around spring break holidays) is somewhat busier than other times of the year at the park.

For your best chance of having the park all to yourself, come in the early fall, winter, or summer, visit during the week, and arrive early in the morning.

Where to stay when visiting Guadalupe Mountains National Park

There are no National Park Lodges within Guadalupe Mountains NP.

The majority of lodging is located in Carlsbad, New Mexico

Holiday Inn Express Carlsbad - Consider a stay at Holiday Inn Express Carlsbad, an IHG Hotel and take advantage of a free breakfast buffet, laundry facilities, and a gym. In addition to a business center, guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi.

Comfort Suites Carlsbad - look forward to a grocery/convenience store, a terrace, and laundry facilities at Comfort Suites Carlsbad. For some rest and relaxation, visit the hot tub. In addition to a gym and a 24-hour business center, guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi.

Quality Inn And Suites - A free breakfast buffet, a terrace, and a garden are just a few of the amenities provided at Quality Inn And Suites. Stay connected with free in-room Wi-Fi, and guests can find other amenities such as laundry facilities and a 24-hour gym.

La Quinta Inn & Suites by Wyndham Carlsbad - Take advantage of a free breakfast buffet, laundry facilities, and a fireplace in the lobby at La Quinta Inn & Suites by Wyndham Carlsbad. Stay connected with free in-room Wi-Fi, and guests can find other amenities such as a gym and a business center.

Fairfield Inn & Suites by Marriott Carlsbad - look forward to free to-go breakfast, laundry facilities, and a 24-hour gym at Fairfield Inn & Suites by Marriott Carlsbad. In addition to a 24-hour business center, guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi

Click on the map below to see additional hotels and vacation rentals near the park.

National Park Camping

There are two developed campgrounds at Guadalupe Mountains National Park.

Located near the visitor center on the south side of the park, Pine Springs Campground is the most convenient campground and, therefore, the most popular. All 33 sites (20 tent and 13 RV) are available on a first-come-first-served basis. Sites fill up quickly, especially on the weekends, so be sure to arrive early if you hope to snag a spot.

Pine Springs Campground also has two group campsites for groups of 10-20 that can be reserved up to 60 days in advance.

The campground offers potable water, flush toilets, and utility sinks but no showers.

Dog Canyon Campground is located on the remote northern side of the park in a secluded canyon. It can take up to three hours driving along the backside of the park to reach Dog Canyon Campground, so it stands to reason that this spot is much less popular than Pine Springs Campground. All 13 (nine tent and four RV) sites are available on a first-come-first-served basis.

Dog Canyon Campground also has one group site for groups of 10-20 that can be reserved up to 60 days in advance.

The campground offers potable water, restrooms with sinks, and flush toilets but no showers.

There are also 10 wilderness campsites available within the park. A backcountry permit is required and can be obtained at the Pine Springs Visitor Center of the Dog Canyon Ranger Station for free.

For a fun adventure check out Escape Campervans. These campervans have built in beds, kitchen area with refrigerators, and more. You can have them fully set up with kitchen supplies, bedding, and other fun extras. They are painted with epic designs you can't miss!

Escape Campervans has offices in Vancouver, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Denver, New York, and Orlando

Parks Near Guadalupe Mountains National Park

Fort Davis National Historic Site

Amistad National Recreation Area

Tumacacori National Historical Park

Check out all of the Texas National Parks along with neighboring National Parks in Oklahoma, National Parks in New Mexico, Louisiana national Parks, and Arkansas National Parks

Make sure to follow Park Ranger John on Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, and TikTok