Complete guide to Capitol Reef National Park in Utah, including things to do, camping, lodging, history, and so much more.

Capitol Reef National Park

About Capitol Reef National Park

Capitol Reef is the least visited of Utah’s “Mighty Five” National Parks. Those who skip this southern Utah Park miss out on much more than rugged desert scenery, however.

This unique park is an eclectic mix of historic landmarks, otherworldly rock formations, and some seriously spectacular landscapes.

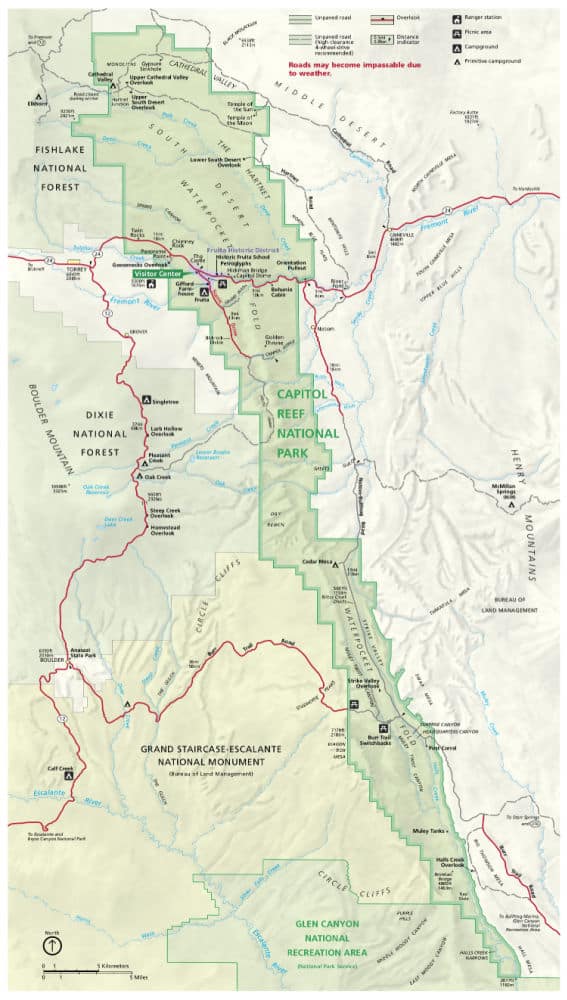

Visitors to Capitol Reef National Park can expect a collection of epic hiking trails, beautiful scenic drives, a wide variety of ranger programs, and much more. The park is split into three districts:

Cathedral Valley District

Located in the northern section of Capitol Reef, the Cathedral Valley District is one of the more remote areas of the park.

Towering sandstone monoliths dominate the rugged desert landscape, and the best way to explore this area is by driving the scenic roads - using a vehicle with AWD is highly recommended.

Fruita Historic District

The Fruita District is famous for its historic buildings and lush valleys. It’s the most accessible district in the park and home to some of Capitol Reef’s top attractions, including historic buildings from the Mormon Homestead and some well-maintained orchards.

Unsurprisingly, this is the park's most popular district.

Waterpocket Fold District

This is the most remote area of the park, and it's located in the southern region of Capitol Reef.

You’ll have to have a strong desire to trek into this area of the park, in addition to a reliable AWD vehicle! The best way to access the Waterpocket Fold District is via the Burr Trail Scenic Byway.

Is Capitol Reef National Park worth visiting?

Many people skip over Capital Reef in lieu of Utah’s other famous national parks, but this gem is absolutely worth a visit!

It offers the same rugged scenery and unique rock formations, plus some historic buildings and abundant orchards - all with fewer crowds!

History of Capitol Reef National Park

The park preserves a large section of the Waterpocket Fold, a 100-mile “wrinkle” in the earth that rises as high as 7,000 feet in certain areas.

The monocline (the wrinkle’s technical name) was created between 50 and 70 million years ago, and since its inception, various arches, towers, canyons, and other noteworthy geological features have been formed along its steep incline.

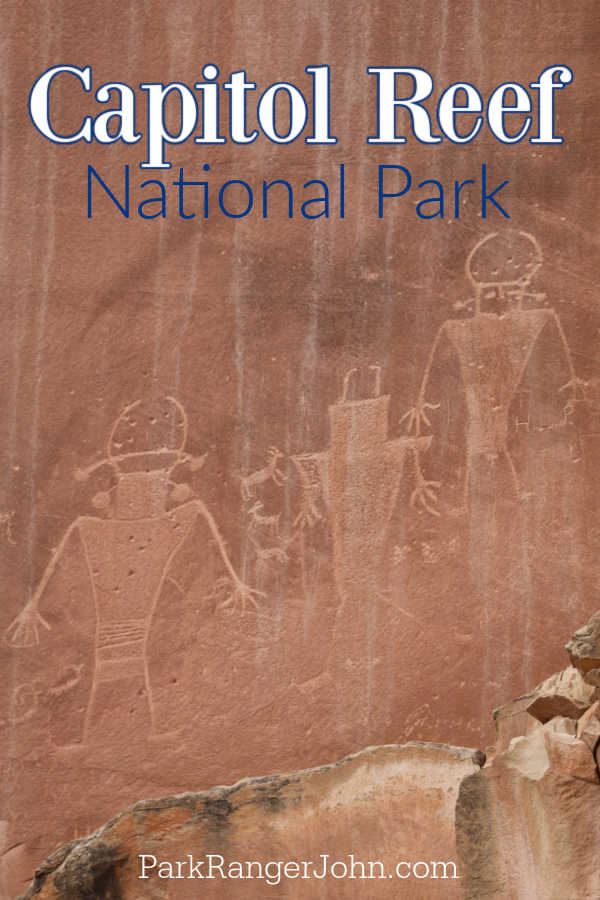

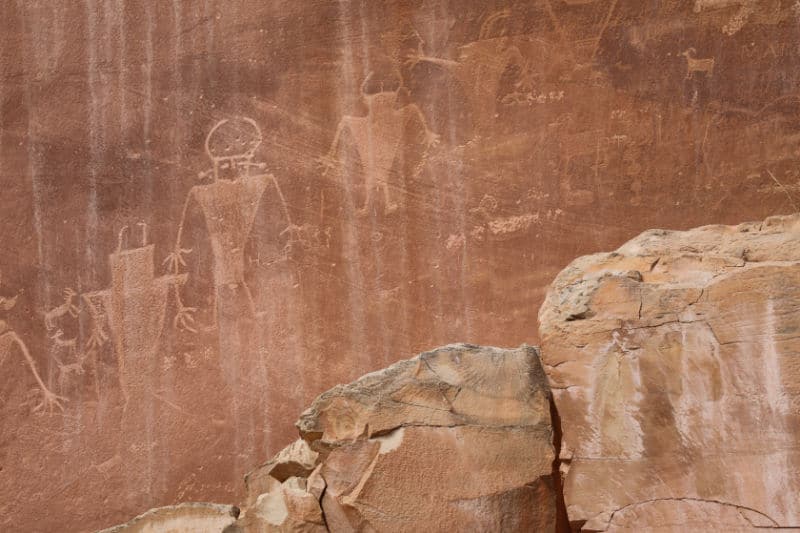

The northern corner of Capitol Reef was home to the indigenous Fremont people from 800 to 1250 AD, and you can still see evidence of their existence from petroglyphs carved into the rocks.

Other tribes later settled in this region, likely due to the protection from the cliffs and the abundant Fremont River.

In the late 1800s, Mormon pioneers came to the area and created Junction - a settlement later referred to as Fruita.

This thriving area contained homesteads, a schoolhouse, orchards, and more, and some of these still stand in the park to this day.

The area was designated as a national monument in 1937 and was later declared a national park in 1967.

Things to know before your visit to Capitol Reef National Park

Capitol Reef National Park Entrance Fee

Park entrance fees are separate from camping and lodging fees.

Park Entrance Pass - $20.00 Per private vehicle (valid for 1-7 days from the date of purchase)

Park Entrance Pass - Motorcycle - $15.00 Per motorcycle (valid for 1-7 days from the date of purchase)

Per-Person Entrance Pass - $10.00 Visitors 16 years or older who enter on foot, bicycle, or as part of an organized group not involved in a commercial tour.

Annual Park Entrance Pass - $35.00, Admits pass holder and all passengers in a non-commercial vehicle. Valid for one year from the month of purchase.

$30.00 for Commercial Sedan with 1-6 seats and non-commercial groups (16+ persons)

$40.00 for Commercial Van with 7-15 seats

$40.00 for Commercial Mini-Bus with 16-25 seats

$100.00 for Commercial Motor Coach with 26+ seats

Learn more about National Park Passes for parks that have an entrance fee.

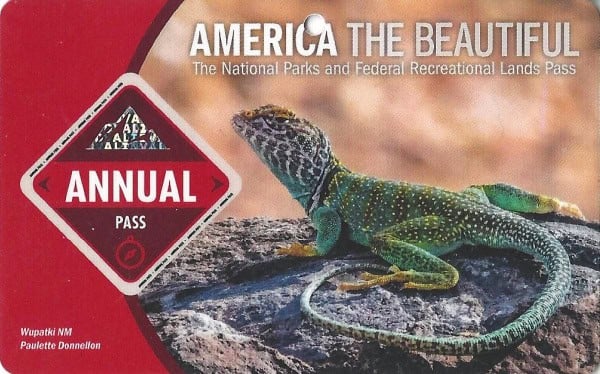

$80.00 - For the America the Beautiful/National Park Pass. The pass covers entrance fees to all US National Park Sites and over 2,000 Federal Recreation Fee Sites for an entire year and covers everyone in the car for per-vehicle sites and up to 4 adults for per-person sites.

Buy your pass at this link, and REI will donate 10% of pass proceeds to the National Forest Foundation, National Park Foundation, and the U.S. Endowment for Forestry & Communities.

National Park Free Entrance Days -Mark your calendars with the five free entrance days the National Park Service offers annually.

Time Zone

Mountain Time

Pets

Pets are allowed in the park on a leash 6 feet or less. Pets are allowed in the following areas:

- on the trail from the visitor center to the Fruita Campground

- on the Fremont River Trail from the campground to the south end of Hattie's Field (where there is a gate)

- in unfenced and/or unlocked orchards

- in the Chestnut and Doc Inglesby picnic areas

- in campgrounds

- within 50 feet of centerline of roads (paved and dirt) open to public vehicle travel

- parking areas open to public vehicle travel

Pets are not allowed on any other hiking trails, in buildings, or in the backcountry.

Cell Service

There is little to no cell phone reception in the park. We randomly had service in a couple of areas but it was not for long.

The closest town with cell reception is Torrey, Utah approximately 11 miles from the visitor center or Hanksville, Utah approximately 37 miles from the visitor center.

Park Hours

The park is open 24 hours a day all year long.

The visitor center is open daily except for on major holidays.

Visitor Center hours vary depending on the season you are visiting in. The best way to get the most up to date hours is by calling 435-425-3791.

Wi-Fi

Limited Wi-Fi is available at the visitor center.

Parking

Limited parking is available at the Visitor Center, various trailheads, lookout points, and other attractions around the park.

Food/Restaurants

The Gifford House in Fruita within the park sells epic baked goods! Get double the pies you think you will want they are that good.

They also have coffee and tea, canned goods, ice cream, and other snacks during spring and summer.

The visitor center also has snacks available and a vending machine for drinks.

Gas

There are no gas stations within the park.

Drones

Drones are not permitted within National Park Sites.

National Park Passport Stamps

National Park Passport stamps can be found in the visitor center.

We like to use these circle stickers for park stamps so we don't have to bring our passport book with us on every trip.

The National Park Passport Book program is a great way to document all of the parks you have visitied.

You can get Passport Stickers and Annual Stamp Sets to help enhance your Passport Book.

Capital Reef NP is part of the 2010 Passport Stamp Set

Electric Vehicle Charging

The closest EV Charging Stations are in Torrey, Boulder, and Escalante, Utah.

Broken Spur Inn and Steakhouse off of Utah 24 has two Tesla Destination Chargers.

Rim Rock Patio has a NEMA outlet.

The following campgrounds in Torrey, Utah also have chargers - Wonderland RV Park, Sand Creek RV Park, and Thousand Lakes RV Park.

Don't forget to pack

Insect repellent is always a great idea outdoors, especially around any body of water.

We use Permethrin Spray on our clothes before our park trips. Please read my article on preventing biting insects while enjoying the outdoors.

Sunscreen - I buy environmentally friendly sunscreen whenever possible because you inevitably pull it out at the beach.

Bring your water bottle and plenty of water with you. Plastic water bottles are not sold in the park.

Sunglasses - I always bring sunglasses with me. I personally love Goodr sunglasses because they are lightweight, durable, and have awesome National Park Designs from several National Parks like Joshua Tree, Yellowstone, Hawaii Volcanoes, Acadia, Denali, and more!

Click here to get your National Parks Edition of Goodr Sunglasses!

Binoculars/Spotting Scope - These will help spot birds and wildlife and make them easier to identify. We tend to see waterfowl in the distance, and they are always just a bit too far to identify them without binoculars.

Details about Capitol Reef National Park

Size - 241,904 acres

Capital Reef NP is currently ranked at 29 out of 63 National Parks by Size.

Date Established

December 18, 1971 by President Richard Nixon

Visitation

In 2021, Capital Reef NP had 1,405,353 park visitors.

In 2020, Capital Reef NP had 981,038 park visitors.

In 2019, Capital Reef NP had 1,226,519 park visitors.

Learn more about the most visited and least visited National Parks in the US

National Park Address

52 West Headquarters Drive

Torrey, UT 84775

Capitol Reef National Park Map

For a more detailed map, we like the National Geographic Trails Illustrated Maps available on Amazon.

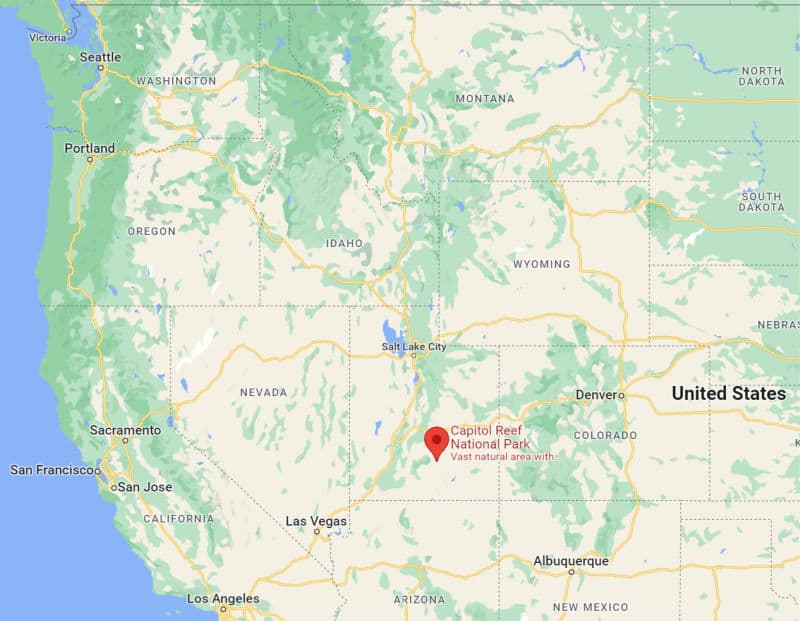

Where is Capitol Reef National Park?

Capitol Reef is located in the desert of south-central Utah.

Estimated distance from major cities nearby

Mileage calculated to the Capitol Reef NP Visitor Center.

Salt Lake City, UT- 223 miles

Henderson, NV - 353 miles

Las Vegas, NV - 334 miles

Paradise, NV - 340 miles

Glendale, AZ - 531 miles

Scottsdale, AZ - 544 miles

Phoenix, AZ - 535 miles

Albuquerque, NM - 511 miles

Estimated Distance from nearby National Parks

Bryce Canyon National Park - 118 miles

Canyonlands National Park - 156 miles

Arches National Park - 142 miles

Zion National Park - 192 miles

Mesa Verde National Park - 270 miles

Great Basin National Park - 241 miles

Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park - 266 miles

Where is the National Park Visitor Center?

The Capitol Reef Visitor Center is located in the Fruita District off of the scenic Highway 24.

Address: 52 Scenic Drive, Torrey, UT, 84775

Getting to Capitol Reef National Park

Closest Airports

Canyonlands Field, Moab, UT (CNY)

International Airports

Salt Lake City International Airport (SLC)

Las Vegas, NV (LAS)

Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport (PHX)

Regional Airports

Cedar City Regional Airport (CDC)

Grand Canyon National Park Airport (GCN)

Provo Municipal Airport (PVU)

Driving Directions

From I-70: Take exit 149, then take UT-24 west toward Hanksville; continue for 43.8 miles (70.5 km). Turn right to continue on UT-24 west and continue for 37.3 miles (60 km).

From I-15: take exit 188 then US-50 east toward Scipio. Left on UT-50; continuing 0.7 miles (1.1 km).

Turn right onto US-50 East; continue for 24.4 miles (39.3 km). Turn right onto UT-260 south and continue 4.2 miles (6.8 km), then right on UT-24 for 71.3 miles. UT-12: North on highway 12 to Torrey, UT. Right onto UT-24.

Best time to visit Capitol Reef National Park

Although Capitol Reef National Park is open year-round, the best times to visit the park are when the weather is at its most mild. This is usually in the Spring and Fall.

Weather and Seasons

Spring

Spring is one of the best times to visit the park. The temperatures are hot but not unbearable, allowing visitors to enjoy all of the park’s outdoor activities.

Spring is also the time of year when the orchards in the Fruita District are in full bloom, creating a beautiful contrast against the red rocks in the distance.

If you want to avoid the crowds, try to visit in early spring, as May is the busiest month at Capitol Reef.

Summer

Because of the soaring temps, summer sees fewer visitors than spring and fall.

By June, highs can reach into the 80s and 90s, so it's best to plan your activities for early in the morning or in the evening. Of course, you could always stick to the scenic drives and crank the A/C!

Autumn/Fall

Autumn is another great time to visit Capitol Reef NP. The temperatures have cooled, making it easy to enjoy outdoor activities around the clock.

In addition, the fall foliage during this season is magnificent, specifically the bright yellow cottonwood trees.

Winter

The best part about visiting the park in the winter is that the crowds are few and far between.

The downside is that temperatures are often below freezing, and snow can limit your ability to hike and drive within the park. That being said, the snow does make for a beautiful contrast against the red rocks!

Best Things to do in Capitol Reef National Park

Scenic Drives

Highway 24

This is the main road that cuts through the park from east to west along the Fremont River.

Along this scenic stretch, you’ll drive past massive Navajo sandstone in the form of domes and cliffs, orchard-covered valleys, historic buildings, red sandstone mountains, and unique rock formations and cliffs.

There are tons of scenic overlooks along this route, and the best part is there is no fee to drive this 16-mile stretch.

Capitol Reef Scenic Drive

If you’re short on time and want a good summary of the park, the 7.9-mile Capitol Reef Scenic Drive is the perfect activity.

The scenic drive starts in the historic Fruita District and ends at Capitol Gorge Road.

Of course, if you do have time, this is also a great way to spend an entire day.

There are tons of viewpoints and hiking trails along the road, and if you have a vehicle with AWD, you can continue onto the unpaved two-mile Capitol Gorge Road at the end of the route.

Note that if you do not have a National Park Pass, there is a $20 fee to access this scenic route.

Cathedral Valley

Cathedral Valley is perhaps one of my favorite scenic drives in the National Park system! It starts with Fjording a river, driving through some sandy areas, and driving through otherworldly landscapes like the Bentonite Hills.

This area is known for its spectacular desert landscapes and massive iconic monoliths including The Temple of the Moon and The Temple of the Sun.

This 57.6-mile trip does require advance preparation as it is extremely remote and odds are that you may not see anyone else the entire day!

Make sure to carry a map, and plenty of water, drive a reliable 4X4 vehicle, and check with the ranger station on road conditions before heading out as sometimes the road is inaccessible due to weather conditions.

If you are not comfortable driving the dirt roads you can book a guided tour of Cathedral Valley.

Burr Trail Scenic Byway

Those with 4WD and a sense of adventure can check out the backcountry Burr Trail Scenic Byway.

This 67-mile route is as rugged as it is scenic.

You’ll pass by red rock formations, tiny towns, and lovely Lake Powell before descending along a series of terror-inducing switchbacks through the Waterpocket Fold.

Fruit Picking

Thousands of fruit and nut trees are thriving in the Fruita District, with heirloom varieties of apricots, apples, cherries, peaches, pears, and plums.

These orchards date back to the late 1800s when the Mormon pioneers planted them.

Visitors are allowed to pick fruit from the orchards year-round, and you’ll know when the harvest is ripe for the picking by the u-pick signs placed outside the orchard.

Note that all fruit must be weighed and paid for.

Wildlife Viewing

Capitol Reef encompasses a wide variety of ecological zones, and with the diversity comes an eclectic cast of park residents.

There are mammals both big and small, including mountain lions, desert bighorn sheep, mule deer, tons of squirrels, marmots, beavers, cave bats, and more.

There are also plenty of amphibians and reptiles - including rattlesnakes - so hike with caution!

Bird Watching

The park’s diverse landscape is also a habitat for many bird species, including wren, eagles, Mexican spotted owls, and the endangered Peregrine falcon.

Smaller bird species are best spotted in the crevices of rock ledges, while larger species will most likely be seen soaring above the canyons or hanging out on cliff ledges.

The Fremont River Trail is another excellent place for birding in the park.

Junior Ranger Program

Visitors both young and old can partake in the park’s Junior Ranger Program.

Not only is it a fun way to learn more about the park’s history, wildlife, and more, but once you complete the program, you’ll get a cool badge to add to your collection.

Ranger Programs

Capitol Reef puts on tons of fantastic ranger programs, including guided hikes, full moon walks, star talks, and more.

Most of these programs are held between June and October, but some you can find year-round, like Geology Talks and the Junior Ranger Program.

Head to the visitor center to learn more about which programs are available during your visit.

Guided Tours of Capitol Reef NP

If you are looking to get out and explore the park with a guide here are some fantastic options.

Milky Way Portraits and Stargazing - Take in the wonders of the universe with a guide on a stargazing tour from Torrey to Capitol Reef National Park. Enjoy hotel transfers and take home a Milky Way portrait from your experience.

Bryce Canyon and Capitol Reef Airplane Tour - Explore two of Utah’s Mighty 5 National Parks on this private airplane tour: Bryce Canyon National Park and Capitol Reef National Park.

From Salt Lake City - Private tour of Capitol Reef

Enjoy the benefits of a private tour and explore the peaceful landscapes of Capitol Reef NP and learn about the historic people who inhabited this desert oasis.

Hiking in Capitol Reef National Park

Always carry the 10 essentials for outdoor survival when exploring.

There are tons of trails in Capitol Reef National Park, so whether you’re looking for a leisurely stroll with great views or an all-day trek through some of the park’s coolest rock formations, we’ve got you covered.

Note that hiking in the summer is not recommended due to the high temperatures. Flash flooding is also common after big storms. Always check the weather and trail conditions before heading out.

Grand Wash Trail

Distance - 5.0 miles

Trail Difficulty - Easy

Time Required - 2 hours

Trailhead - Fruita District

Following a wide sandy trail, this hike leads you through the Grand Wash Canyon in the Waterpocket Fold.

This hike is all about the sandstone cliffs and rock formations that surround the trail, so you can turn around before the end of the five miles if you are looking for a shorter hike.

Red Canyon Trail

Distance - 5.6 miles

Trail Difficulty - Easy

Time Required - 2 hours

Trailhead - Waterpocket District

This route meanders through the sagebrush flats of the Waterpocket District. As you hike, you’ll take in epic views of the Henry Mountains, along with the high sandy walls of Red Canyon.

There are tons of cool plant life along this trail as well, especially if you’re hiking during the spring and early summer.

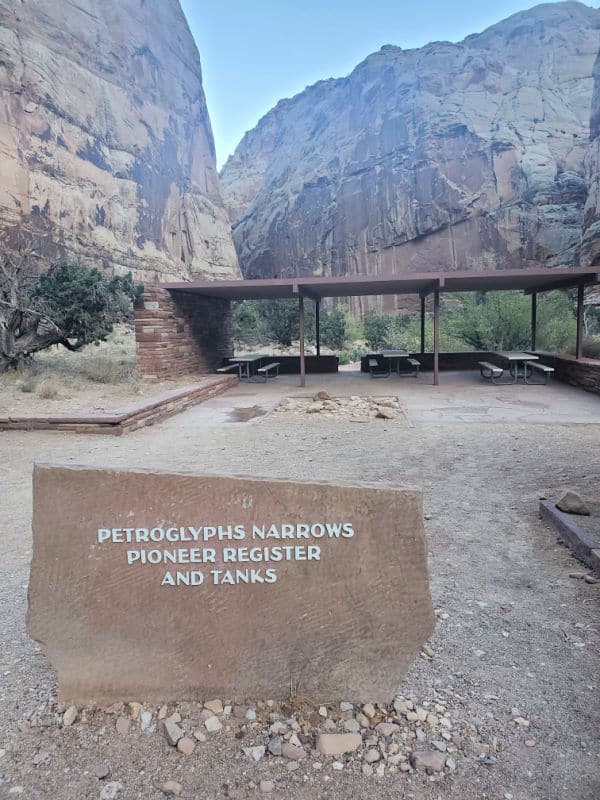

Capitol Gorge Trail

Distance - 4.5 miles

Trail Difficulty - Moderate

Time Required - 1.75 hour

Trailhead - Fruita District

As you trek through the gorge, you’ll encounter various historical sites, including petroglyphs created by ancient tribes and inscriptions carved into the rock walls (also known as the Pioneer Register) by settlers and miners from the late 1800s and early 1900s.

From there, you’ll come upon “the tanks” - large natural water pockets that often fill with rain.

Hickman Bridge Trail

Distance - 1.7 miles

Trail Difficulty - Moderate

Time Required - 1.5 hours

Trailhead - Fruita District

This is one of the most popular trails in the park. It’s a relatively short route that leads to some epic rock formations that are reminiscent of some of Utah’s other national parks.

The highlight is the Hickman Bridge, a 133-foot natural arch situated at the back of the canyon.

There is little shade along this route so bring plenty of sun protection and water!

Cassidy Arch Trail

Distance - 3.1 miles

Trail Difficulty - Hard

Time Required - 2 hours

Trailhead - Fruita District

Although a bit more strenuous than some of the other hikes in the park, Cassidy Arch Trail is perhaps the most popular route.

The natural bridge at the end (Cassidy Arch) is the main draw to this trail, but the epic views across Grand Wash are likely what you’ll remember most from this challenging trek.

Navajo Knobs

Distance - 9.5 miles

Trail Difficulty - Hard

Time Required - 4.5 hours

Trailhead - Fruita District

Although long and strenuous, the incline along this route is fairly steady the whole way.

This hike is all about the stunning vistas, and if you don’t feel like hiking the full trail, you can turn around at the first major lookout point - Rim Overlook.

Those who do make it all the way to the top will be rewarded with breathtaking 360-degree views across the park.

How to beat the crowds in Capitol Reef National Park?

The busiest time of year at Capitol Reef NP is between May and June and September and October. If you want to avoid the crowds, consider planning your trip for the off-season.

If you don’t want to contend with extreme weather (90-degree heat in the summer and snow in the winter), then March and November are the best times to avoid the crowds.

Where to stay when visiting Capitol Reef National Park

There are no National Park Lodges within the park.

The closest lodging is in Torrey, Teasdale, and Grover, Utah.

Capitol Reef Resort - Located right outside of the park offers epic lodging options.

Days Inn Capitol Reef - This hotel is 4 miles from the park and offers free Wi-Fi, cable tv, a pool, and more.

Broken Spur Inn & Steakhouse - This hotel has breakfast included and is close to the park.

For additional hotels and vacation rentals click on the map below

Capitol Reef Camping

Fruita Campground

Fruita Campground is located in the historic orchards of the Fruita Historic District along the Fremont River.

There are 71 sites for tents and small RVs. Each site is equipped with a picnic table and firepit. No hook-ups are available.

There are restrooms with flush toilets, an RV dump station, and a potable water filling station.

The campground is open year-round, and reservations are available up to six months in advance for the March-October season.

Primitive Campgrounds

Cathedral Valley Primitive Campground

This primitive campground is located in the Cathedral Valley District. There are six sites available on a first-come-first-served basis. Sites are free and open year-round.

Cedar Mesa Primitive Campground

This primitive campground is located in the Waterpocket Fold District. There are five sites available on a first-come-first-served basis. Sites are free and open year-round.

Backpacking Camping

Backcountry camping is allowed at Capitol Reef National Park. A permit is required and can be acquired at the Visitor Center for free.

Most choose to hunker down along one of the six main backpacking routes. For more info, check in with a ranger at the Visitor Center.

Capitol Reef National Park Group Campsite

There is one group campsite available near the Fruita District. The site can host up to 40 people and can be reserved up to 12 months in advance.

For a fun adventure check out Escape Campervans. These campervans have built in beds, kitchen area with refrigerators, and more. You can have them fully set up with kitchen supplies, bedding, and other fun extras. They are painted with epic designs you can't miss!

Escape Campervans has offices in Vancouver, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Denver, New York, and Orlando

Parks Near Capitol Reef National Park

Timpanogos Cave National Monument - 200 miles

Natural Bridges National Monument - 170 miles

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Bullfrog Marina - 104 miles

Hovenweep National Monument - 266 miles

Cedar Breaks National Monument - 149 miles

Check out all of the National Parks in Utah along with neighboring National Parks in Arizona, National Parks in Colorado, National Parks in Idaho, Nevada National Parks, New Mexico National Parks, and Wyoming National Parks

Make sure to follow Park Ranger John on Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, and TikTok