Complete Guide to Shenandoah National Park in Virginia, including things to do, where to stay, camping, history, and so much more.

Shenandoah National Park

Spread across 199,223 acres in the state of Virginia along the cascading Blue Ridge Mountains is Shenandoah National Park!

If you’re looking for a park that isn’t too crowded all the time but boasts natural landscapes that will take your breath away, this expansive national park with diverse topography includes some of the most iconic trails, overlooks, and waterfalls and is the perfect place for you!

The park is known for having up to 500 miles of trails, along with a hundred and one miles of the infamous Appalachian Trail as well.

You’ll also find gems like widespread wetlands, jagged peaks like the Old Rag and Hawksbill mountains, and wildlife like black bears.

The national park is known for having one of the densest populations of bears.

This long and vast national park is set along the awe-inspiring Blue Ridge Mountains, with so much to see and do.

Check on the weather, carry your essentials and proper hiking gear, and spend at least a night in a lodge or campground within the park boundary to get the best of Shenandoah National Park!

About Shenandoah National Park

Located a short road trip from the US capital, Shenandoah National Park is a region of diverse, lush landscapes, unique wildlife, breathtaking mountain peaks, cascading waterfalls, and the list goes on.

Shenandoah National Park is situated between the Shenandoah Valley in the east and the Piedmont region in the west and comprises a large area of wetlands and forests with occasional overlooks from jagged peaks and, of course, a stellar view of the Blue Ridges.

The park is home to Skyline Drive, an iconic 105-mile road that runs through the entire length of the Shenandoah National Park along the Blue Ridge Mountains, which causes most people to just drive through the park instead of spending a couple of days exploring it.

However, with so much to offer, the park is a tranquil paradise, perfect for those looking for a peaceful escape and also doubles as one of the top places for an adventure junkie as it has all the backcountry sports you can think of and more.

Besides being one of the top parks to go to with your pet (as they can accompany you on most trails), it is also highly user-friendly, easy to navigate, and has so much to see in every direction you go.

At the park, you’ll be able to explore up to 500 miles of hiking trails, including 101 miles of the infamous Appalachian trail, go fly-fishing (and you’ll have a chance to find some of the best trout in the region), rock-climbing up the ragged cliffs of Shenandoah, and so much more.

The opportunities in this nature’s haven are endless.

You’ll also get a chance to spot wildlife, including Deer, Racoons, Fox, and Coyotes, and the park is also known for having one of the densest populations of Black Bears, so you’re unlikely to come back without spotting at least one.

You’re also sure to find some Butterflies, Owls, Turkeys, and some genuinely magnificent birds for the bird-watcher in you like the Scarlet Tanager, Peregrine Falcon, Cerulean Warbler, and so many more.

The unique formation of the region gives rise to several different landscapes inhabited by a variety of wildlife, making the Shenandoah National Park truly a delight to explore, forage through, and learn from.

The serene atmosphere of the valley, combined with the dramatic views of the awe-inspiring Blue Ridge mountains, makes the region of the most underrated national parks in the entire country.

Bonus: If you happen to visit in the fall, the orange and red foliage combined with the pleasant weather and frequent wildlife will make it very hard to leave!

Is Shenandoah National Park worth visiting?

Absolutely yes! Shenandoah has so much to offer from hiking, scenic driving, breathtaking sunsets and overlooks, and fantastic lodges to somewhere you can just relax and just get away from the big city and enjoy nature and wildlife. This park has something for everyone.

History of Shenandoah National Park

The history of the iconic Shenandoah National Park dates back to a billion years ago, when the earth’s crust led to the formation of jagged scenic peaks that now make up the beautiful Blue Ridge Mountains of the South.

Ever since that, the land around the mountains and beyond has been cultivated into expansive wetlands and unique topographies that became home to many unique and indigenous flora and fauna.

Fast forward to about ten thousand years ago, it’s believed that many tribes of Native Americans began to tour the region for hunting and sourcing and ultimately settled in the area combining their home and livelihood.

After inhabiting and nurturing the area for many centuries, the Native American Tribes met with European visitors who began as hunters and trappers and ultimately took to infrastructure development.

The untouched natural beauty of the forest suddenly became mechanized, with resources being mined, crops being harvested, and the foundation for lodging and homesteading being laid.

Legislation to create a national park that preserved the environment and provided joy and employment to the people in and around the region of the Appalachian mountains was put forth back in 1901 by Henry D. Flood, a Virginia congressman.

Even though President Theodore D. Roosevelt backed it, the act, unfortunately, did not pass at the time.

With time, the area began to attract more and more interest from legislators to declare it a reserve of sorts and from tourists looking for the perfect nature getaway, an escape from the rat race of the early 20th century.

However, it’s important to remember that the area up until now was still home to the tribes that took care of the environment and bred it into the gorgeous landscape it is today, and as a result of the continued interest in the area, many of these people were forced out of their homes.

Many Natives staged demonstrations and protests in retaliation, asking the legislators to stop their displacement and recognize that the place had been their home and source of livelihood for generations.

Years after, a common ground was reached, and after the National Park Service’s establishment in 1916, legislation to declare this region the Shenandoah National Park was drawn up.

Simultaneously, while the region was being developed and growing in popularity, it was also under Jim Crow Virginia, leading to segregation of the facilities amongst the public, which was discriminatory for all the non-whites and disallowed them to make the most of the region.

With the onset of World War II, Skyline Drive and the heart of the park was completed, and post the war and devastation, the National Park Service took a stand and introduced the necessary policy that called for desegregation of all facilities in the park.

The region was finally established as a National Park on December 26th, 1935, and officially declared open by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on July 3rd, 1936.

Following this, Congress went on to declare over half the park as protected wilderness.

Today, the park is a favorite amongst adventure seekers and outdoor enthusiasts as it combines challenging and complex trails and hikes with breathtaking valleys and wetlands overseeing the tall peaks of the Blue Ridges.

Things to know before your visit to Shenandoah National Park

Shenandoah National Park Entrance Fee

Park entrance fees are separate from camping and lodging fees.

Park Entrance Pass - $30.00 Per private vehicle (valid for 1-7 days from the date of purchase)

Park Entrance Pass - Motorcycle/snowmobile - $25.00 Per motorcycle/snowmobile (valid for 1-7 days from the date of purchase)

Per-Person Entrance Pass - $15.00 Visitors 16 years or older who enter on foot, bicycle, or as part of an organized group not involved in a commercial tour.

Annual Park Entrance Pass - $55.00, Admits pass holder and all passengers in a non-commercial vehicle. Valid for one year from the month of purchase.

$0.00 Education/Academic Group

$35.00-$75.00 for vehicles with 1-6 seats and non-commercial groups, $25.00 + $10.00 per passenger

$75.00 for vehicles with 7-15 seats

$100.00 vehicles with 16-25 seats

$200.00 for vehicles with 26+ seats

$15.00 per person for Non-commercial group (16+ persons)

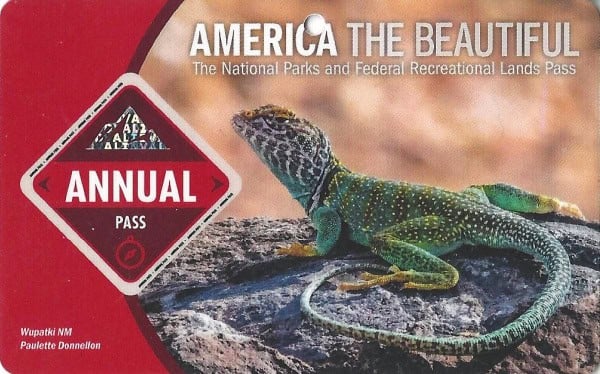

Learn more about National Park Passes for parks that have an entrance fee.

$80.00 - For the America the Beautiful/National Park Pass. The pass covers entrance fees to all US National Park Sites and over 2,000 Federal Recreation Fee Sites for an entire year and covers everyone in the car for per-vehicle sites and up to 4 adults for per-person sites.

Buy your pass at this link, and REI will donate 10% of pass proceeds to the National Forest Foundation, National Park Foundation, and the U.S. Endowment for Forestry & Communities.

National Park Free Entrance Days -Mark your calendars with the five free entrance days the National Park Service offers annually.

Time Zone

Eastern Time Zone

Pets

One of the most dog-friendly parks in the National Park System, you’ll be able to take your pets on most trails and landscapes; however, it’s important to remember that you’re responsible for them and must follow guidelines to prevent any mishaps.

Be sure to keep your pet on a leash no longer than 6 feet in length.

Pets are, however, not allowed on ranger programs and the following trails:

- Fox Hollow Trail

- Stony Man Trail (except for the portion that follows the Appalachian Trail)

- Limberlost Trail

- Old Rag Ridge Trail

- Old Rag Saddle Trail

- Ridge Access Trail

- Dark Hollow Falls Trail

- Story of the Forest Trail

- Bearfence Mountain Trail

- Frazier Discovery Trail

Cell Service

The cell coverage throughout the park varies according to your region and depends significantly on your cell phone carrier, so it’s best not to rely on your carrier for communication.

It’s known to be the best at some west-facing overlooks and the Dickey Ridge Visitor Center.

Park Hours

Shenandoah National Park is open 24 hours, 365 days a year.

However, some attractions may remain closed in the winter, and since the weather can be unpredictable sometimes, be sure to check real-time updates before you make the trip.

Wi-Fi

Wi-Fi is available in some spots across the park, such as the Byrd Visitor Center, Big Meadows Lodge, and Skyland Resort.

Insect Repellent

It’s always a great idea to apply some insect repellent when you’re heading outdoors, particularly if you’re going to be around water bodies.

We specifically carry and use Permethrin Spray on our clothes before embarking on any outdoor excursions.

Water Bottle

It would be best if you remembered to carry your water bottle and plenty of water with you as you can get dehydrated quickly, especially in the summers, and won’t be able to find any plastic water bottles at the shops in the park.

Parking

There are plenty of parking spaces available in and around the national park. You’ll find spots at trailheads, entrance stations, visitor centers, picnic areas, waysides, and overlooks.

Remember that if you’re parking at overlooks or other such regions, ensure you’re not blocking Skyline Drive or administrative & fire roads.

Food/Restaurants

There are plenty of places to grab a bite or have a proper meal within the Shenandoah National Park.

If you’re hoping to carry a sandwich to eat after you end a hike or want to end the day of exploring with a fine dining meal, you can choose from the following:

- Elkwallow Wayside

At Elkwallow Wayside, you’ll find a selection of breakfast foods, grilled foods for lunch and dinner, and groceries to pick up on the go. The eatery has seating on picnic tables or on the patio outside.

- Skyland Pollock Dining Room

The Skyland Lodge houses the infamous Pollock Dining Room, which is known for offering a proper service dining room with breakfast, lunch, and dinner meal options. At the Mountain Taproom, you’ll find a more relaxed menu with beer, and local wines, accompanied by nightly family-friendly entertainment. The on-site Grab’ n Go has salads, sandwiches, snacks, drinks, and more to purchase while you’re on the go.

- Big Meadows Wayside

If you’re searching for an extensive menu with warm Southern food, Big Meadows Wayside offers authentic favorites. The Grab’ n’ Go has salads, sandwiches, snacks, drinks, and basic groceries to purchase while you’re on the go.

The Spottswood Dining Room, set in the Big Meadows Lodge, is designed keeping in mind the wooden-cabin feel of staying in a vast wooded forest and offers iconic breakfast, lunch, and dinner meals. At the New Market Taproom, you’ll discover a more relaxed menu with drinks, beer, local wines, and more. The place also has a pet-friendly terrace seating option!

- Loft Mountain Wayside

The Loft Mountain Wayside serves several different breakfast foods, sandwiches, and grilled items, and here you can enjoy splendid outdoor seating with a view of the valley!

Gas

Gas is available at Big Meadows Wayside; however, entering the park with a full tank is recommended as the gas pumps can be unreliable, especially in the winter.

Drones

Drones are not permitted within National Park Sites.

National Park Passport Stamps

National Park Passport stamps can be found in the visitor center.

Make sure to bring your National Park Passport Book with you or we like to pack these circle stickers so we don't have to bring our entire book with us.

Shenandoah NP is part of the 1996 Passport Stamp Set.

Electric Vehicle Charging

Charging stations are currently free for the public to use for an electric vehicle or plug-in hybrid. At Shenandoah, you’ll be able to access EV charging stations at the following places:

- Skyland - One Level 2 (J1772) connector and one Level 2 (Tesla) connector

Accessibility

The National Park Service strives to make the parks accessible to all. The Shenandoah National Park has several landmarks that are easily accessible, like visitor centers, self-guided trails, campgrounds, scenic overlooks, and more.

The Limberlost Trail is an elaborate network of accessible trails along with all lodges, restrooms, and campgrounds being accessible according to the ADA guidelines.

You’ll find accessible shower and laundry facilities at Big Meadows, Lewis Mountain, and Loft Mountain campgrounds.

In addition, you’ll be able to pick up assistive listening devices at the visitor centers.

Details about Shenandoah National Park

Size - 199,223 acres

Shenandoah NP is currently ranked at 33 out of 63 National Parks by Size.

Date Established

Though there were hopes to establish a National Park in the Virginia region even before the National Park Service was established in 1916, there were a series of obstacles that prevented this from happening.

Ultimately, the area was declared a National Park on December 26th, 1935. In 1976, the government announced over half of the national park area to be protected wilderness.

Visitation

In 2021, Shenandoah NP had 1,592,312 park visitors.

In 2020, Shenandoah NP had 1,666,265 park visitors.

In 2019, Shenandoah NP had 1,425,507 park visitors.

Learn more about the most visited and least visited National Parks in the US

National Park Address

21073 Skyline Drive

Front Royal, Virginia 22630

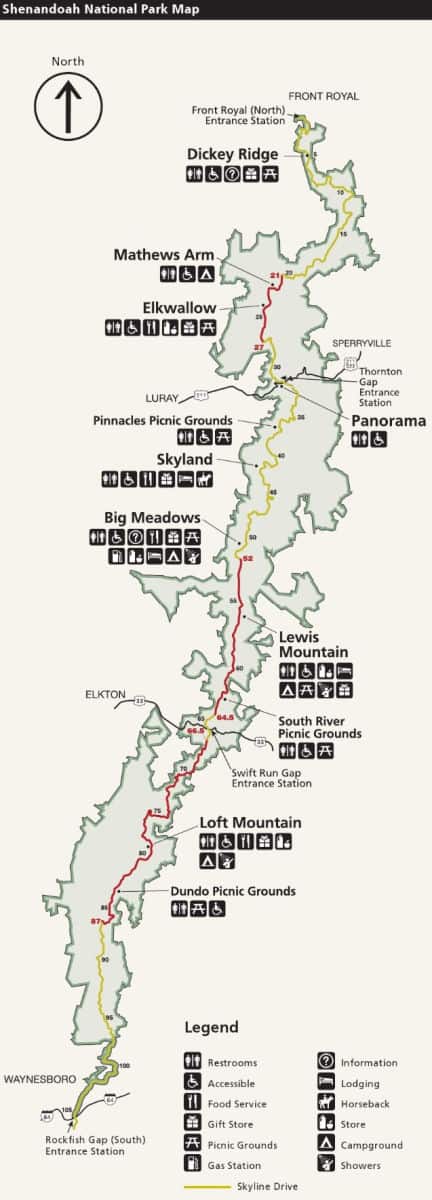

Shenandoah National Park Map

For a more detailed map we like to use the National Geographic Trails Illustrated Maps available on Amazon.

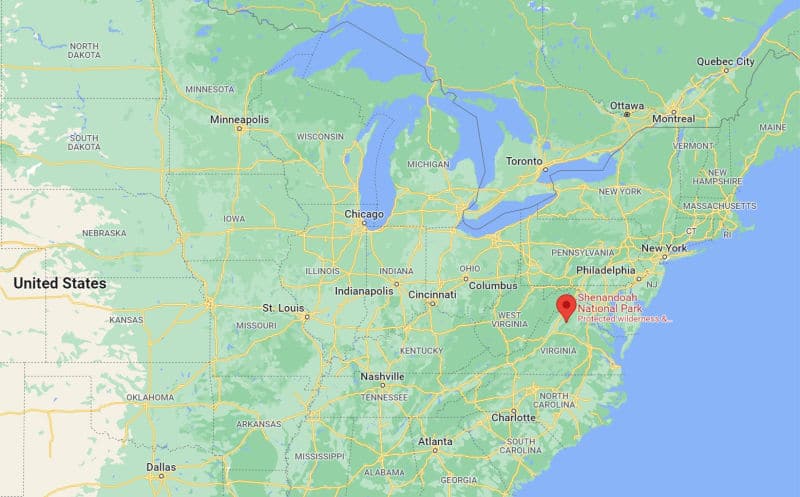

Where is Shenandoah National Park?

Located between the lush green Shenandoah Valley and Piedmont region, a mere 70 miles from Washington DC, the Shenandoah National Park spans 199,223 acres in Virginia, along the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Estimated distance from major cities nearby

Charlottesville, VA - 43 miles

Washington DC - 70.5 miles

Richmond, Virginia - 105 miles

Baltimore, MD - 108 miles

Durham, NC - 180 miles

Norfolk, VA - 185 miles

Chesapeake, VA - 197 miles

Raleigh, NC - 206 miles

Pittsburgh, PA - 214 miles

Estimated Distance from nearby National Park

New River Gorge National Park - 177 miles

Congaree National Park - 382 miles

Mammoth Cave National Park - 539 miles

Cuyahoga Valley National Park - 320 miles

Indiana Dunes National Park - 625 miles

Acadia National Park - 791 miles

Where is the National Park Visitor Center?

The park is home to two main visitor centers and one mobile visitor center, which is a van with knowledgeable park rangers that’ll be more than happy to answer your questions and queries.

- Dickey Ridge Visitor Center

The Dickey Ridge Visitor Center is open to visitors in Spring, Summer, and Fall is closed for the winter season.

Operational Hours: 9:00 AM - 5:00 PM

It is located near Fort Royal, close to one of the park’s entrances, and has a shop to purchase souvenirs, an information center, a theater, NPS and Shenandoah’s publications, maps, and more. You’ll find the Fox Hollow trailhead opposite the visitor center.

- Harry F. Byrd, Sr. Visitor Center

The Harry F. Byrd, Sr. Visitor Center is open to visitors throughout the year.

Operational Hours:

Winter- 9:00 AM - 4:30 PM

Spring, Summer, and Fall - 9:00 AM - 5:00 PM

It is located in the heart of the Shenandoah National Park near the Big Meadows and offers an information desk, ranger programs, bookstore, publications, maps, restrooms, etc. Since it is in the region’s center, it’s the ideal place to begin your next hike or drive to your next attraction.

Getting to Shenandoah National Park

One thing to know about visiting Shenandoah NP is there are four main entrances to the park.

These entrances are spread out so you will want to know which entrance you plan to enter and exit with and what you want to see near the entrance.

The Entrance Stations are:

Front Royal - North Entrance - Near Front Royal, Virginia, off of Route 340 (also called Stonewall Jackson Highway).

Thornton Gap - East of Luray, Virginia and west of Sperryville, Virginia. Off of Highway 211 (also called Lee Highway).

Swift Run Gap - East of Elkton, Virginia off of US 33.

Rockfish Gap - South Entrance - A few miles east of Waynesboro, Virginia off of Highway 250.

Closest Airports

International Airports

Washington Dulles International (IAD) - 56.9 miles

Reagan National Airport (DCA) - 72.8 miles

Regional Airports

Charlottesville - Albemarle Airport (CHO) - 22.7 miles

Shenandoah Valley Regional (SHD) - 23.3 miles

Driving Directions

From Washington DC

75 miles, 1 hour 15 minutes

You’ll begin your journey in Washington DC by getting on Interstate 66 West towards Warren County.

The road will take you to Virginia, where after about 60 miles, you’ll take Exit 13 towards Virginia Route 79 South.

You’ll turn unto Virginia Route 55 West and take a left onto US Route 340 South. Ultimately, you’ll turn left onto Skyline Drive, making it to your destination!

From Richmond, Virginia

92.7 miles, 1 hour 30 minutes

You’ll begin your trip in Richmond, the capital of Virginia, by getting on Interstate 64 West via North 7th Street.

You’ll merge with Interstate 95 North and continue onto Interstate 64 West heading towards Charlottesville for nearly 90 miles.

You’ll proceed to exit onto US Route 250 East and then take a left onto Skyline Drive, the gateway to Shenandoah National Park!

From Pittsburg, Pennsylvania

214 miles, 3 hours 45 minutes

To get from Pittsburg to Shenandoah, you’ll begin your road trip by getting on Interstate 579 South and immediately taking the exit towards Interstate 376 East.

You’ll proceed to take Exit 85 for Interstate East, and then over a hundred miles after, you’ll continue onto Interstate 70 East which will take you to Maryland.

You’ll then take Exit 1B for US Route 522 South heading towards Hancock, and after entering Virginia, you’ll merge with Virginia route 37 South to take you to Interstate 66 East.

Finally, you’ll take Exit 6 to connect with US 340 South and continue onto Skyline Drive, the scenic hundred-mile road that cuts through Shenandoah National Park.

Best time to visit Shenandoah National Park

The spectacular Shenandoah National Park is an all-weather park, and irrespective of whichever time of year you visit, you’re bound to enjoy your time in this tranquil forested region.

However, with its changing weather conditions and diverse topography, your time at the park in some seasons may turn out to be better than others.

Weather and Seasons

Spring

The Shenandoah National Park is still waking up from the wintertime, so it’s slow in the park during spring.

Most of the region’s campgrounds don’t open until late spring, and the months of March and April can still witness severe chilly winds and even snowfall.

You’ll start seeing wildflowers and other colorful flowers come up in the valley at the tail-end of the season, a sign of the park’s regeneration with the onset of slightly warmer weather.

Summer

A favorite time to visit amongst many, and all for a good reason. Though the summer weather can be sweltering and relatively humid, the park’s trees and plants come alive during this time.

In the summertime, you’ll get a chance to pick fresh blackberries and taste delicacies prepared with them at the park’s restaurants.

It’s also the best time to taste and fall in love with the iconic Shenandoah Valley Wine.

Autumn/Fall

The Shenandoah National Park is known across the country and beyond for the breathtaking form, it takes in the fall.

The pleasant daytime weather coupled with the yellow, orange, and red hues of the leaves makes the fall time a great time to tour the sights of Shenandoah.

It’s the perfect time to explore the RipRap Trail to soak in the best regions of the park in the autumntime.

Since it’s such a favorite time to visit amongst locals and tourists alike, expect traffic and rush and make reservations to stay well before time.

Winter

The weather in the region is pretty mild; however, the area does witness a rare snowstorm, especially since it is home to several high peaks and adjacent to the Blue Ridges.

It is important to note that parts of the Skyline Drive and most of the lodges of the park and camping grounds are closed for the winter, so you’ll have to figure out accommodation elsewhere.

This being said, the park certainly is the best place to be if you’re in search of a wholly isolated trip in the woods.

With fewer crowds and the absence of thick trees, you’ll have a higher chance of spotting some of the park’s wildlife.

Best Things to do in Shenandoah National Park

With the park’s unique climate and topography, there are so many different things to explore and immerse yourself in.

Nature takes on new forms every season, so you’ll find a variety of activities to do no matter what time of year you visit.

Skyline Drive

The crown jewel of the Shenandoah National Park is Skyline Drive, a 105-mile long National Parkway that cuts through the length of the entire national park and offers spectacular vistas.

Surrounded by the Shenandoah Valley and Piedmont Plateau, and the magnificent Blue Ridge Mountains, the route is truly one of the most scenic drives you’ll find in the region.

While the Skyline Drive makes it easy for people to just drive through the park and explore the sights, it’s also the gateway to most of the park’s top attractions and visitor attractions, and stopping at some of the unique landscapes is truly worth it!

Particularly in the autumn, the trees turn all sorts of colors, and driving through the park is truly a dream.

Junior Ranger Program

At the Shenandoah National Park, you can get a Junior Ranger booklet at any park visitor center, and everyone can engage with park rangers to learn more about the park and explore it in a unique manner.

Wildlife/Bird Watching

As the park is more isolated than other famous parks and is densely forested, it is a great place to go wildlife viewing or bird watching.

Several animals and birds call the park their home, including Fox, Coyotes, Deer, Racoons, and of course Black Bear.

The park has one of the densest populations of the Black Bear, so if you’re itching to spot one, Shenandoah is the place to be.

You’ll also spot owls, turkeys, and rare species like Scarlet Tanager, Peregrine Falcon, Cerulean Warbler, etc.

Rapidan Camp

Rapidan Camp was the summer retreat of President Herbert Hoover in the park.

The National Park Service offers 2.5 hour ranger guided tours from late spring through fall.

Rapidan Camp features the presidents cabin, the Brown House, which have been refurnished to their 1929 appearance.

Hiking in Shenandoah National Park

Shenandoah National Park encompasses over 500 miles of trails, including 101 miles of the Appalachian Trail.

You’ll find a variety of courses, each with its challenges and obstacles, and at Shenandoah, you’re more likely to have to do more work for scenic overlooks than in other parks with more accessible hikes to iconic lookouts.

Some notable trails are the Dark Hallow Trail which leads to the tallest waterfall in the park. The Rose River Falls is a 4-mile-loop with several cascading waterfalls along its route.

The challenging but completely worth it Old Rag hike, which is 9.5 miles long and leads you to the top of the peak boasts panoramic views of the forest, valley, sister peaks, and beyond.

Be sure to pick your trails smartly by assessing your abilities and fitness levels, and remember to always carry ten essentials for outdoor survival when exploring the park’s ins and outs.

How to beat the crowds in Shenandoah National Park?

Though the park is massive and doesn’t see as many visitors as icons like the Great Smoky Mountains or Yellowstone, you will be faced with filled parking lots and long queues in its peak season.

A great way to avoid the masses is by planning which part of the park you want to explore each day and arriving early at the attractions.

The winter and early spring don’t see a lot of visitors since a lot of the attractions and accommodations in the area are closed due to harsh weather.

If you’re okay with cold weather and not staying in the park while visiting, touring the park in the off-season is a stellar way to avoid the crowds and explore the tranquil forests and valley of the Shenandoah National Park without the crowds.

Where to stay when visiting Shenandoah National Park

Shenandoah National Park has two iconic wooden lodges and one log cabin, each charming in its own way.

Big Meadows Lodge

Located a mile from the expansive green Big Meadow at mile 51 on Skyline Drive, the Big Meadows Lodge is a spectacular wooden lodge overlooking the park and beyond.

At the lodge, you’ll find lodge rooms, detached petit cabins, suites, pet-friendly rooms, and more.

The lodge is home to the iconic Spottswood Dining Room, the top place to dine in the park, an ATM, the New Market Taproom for a chilled beer to wind down from a hot summer day of exploration, and other basic amenities.

You’ll find cell service and Wi-Fi connectivity in the main areas but not in the rooms, making it a great place to relax.

The Big Meadows Lodge is open for guests in Spring, Summer, and Fall and closed for the winter season. Reservations are recommended and can be made here.

Skyland Lodge

The Skyland Lodge is located in the Skyland region along the Blue Mountain Ridges, at 3,680 feet in elevation.

At the lodge, you’ll find awe-inspiring views of the wetlands and be able to gorge on delicious meals at the Pollock Dining Room Mountain Taproom and purchase souvenirs to take back home from the Skyland Gift Shop.

The lodge is located in the heart of the park, making it the perfect place to begin a new hike or trail from. The rooms are typical wooden lodge rooms with a stone fireplace elevating the space. The lodge comprises individual buildings with several rooms in each.

The Skyland Lodge is open for guests in Spring, Summer, and Fall and closed for the winter season. Reservations are recommended and can be made here.

Lewis Mountain Cabins

Located next to the Lewis Mountain Campground and several trailheads, these cabins are the ideal place to stay while exploring Shenandoah National Park.

You’ll be surrounded by the beautiful and jagged peaks of the Blue Ridges and overlook the forest as you sip on your morning coffee on your cabin’s balcony.

The cabins themselves don’t have any Wi-Fi or cell phone connectivity, making them ideal for a social media detox coupled with a tranquil trip with your partner, family, or friends.

The Lewis Mountain Cabins are open for guests in Spring, Summer, and Fall and closed for the winter season. Reservations are recommended and can be made here.

Lodging near Shenandoah National Park

Hotel Madison & Shenandoah Conference Center - At Hotel Madison & Shenandoah Conference Ctr, you can look forward to a terrace, a coffee shop/café, and dry cleaning/laundry services. The onsite restaurant, Montpelier Restaurant, features brunch and happy hour. In addition to a fireplace in the lobby and a bar, guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi.

The Blackburn Inn - At The Blackburn Inn and Conference Center, you can look forward to a grocery/convenience store, a terrace, and shopping on site. Treat yourself to reflexology, a Swedish massage, or a manicure/pedicure at The Spa at the Blackburn, the onsite spa. Be sure to enjoy a meal at Second Draft, the onsite restaurant. In addition to a coffee shop/café and a garden, guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi.

Clarion Pointe Harrisonburg - At Clarion Pointe Harrisonburg, you can look forward to a free breakfast buffet, a terrace, and a garden. In addition to dry cleaning/laundry services and a 24-hour gym, guests can connect to free in-room Wi-Fi.

The Village Inn Harrisonburg - A playground, laundry facilities, and a 24-hour gym are just a few of the amenities provided at The Village Inn Harrisonburg. The onsite restaurant, The Village Inn, features southern cuisine. Stay connected with free in-room Wi-Fi, and guests can find other amenities such as a business center.

Doubletree by Hilton Harrisonburg - Take advantage of dry cleaning/laundry services, a bar, and a gym at Doubletree by Hilton Harrisonburg. Free Wi-Fi in public areas is available to all guests, along with a 24-hour business center and a restaurant.

Click on the map below to see additional vacation rentals and lodging near the park.

Shenandoah National Park Camping

Camping in Shenandoah National Park is a fantastic way to experience everything the park has to offer.

The campgrounds are spread throughout the park making it a great way to explore different parts of the park during your visit.

For a fun adventure check out Escape Campervans. These campervans have built in beds, kitchen area with refrigerators, and more. You can have them fully set up with kitchen supplies, bedding, and other fun extras. They are painted with epic designs you can't miss!

Escape Campervans has offices in Vancouver, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Denver, New York, and Orlando

Big Meadows Campground

Season: Summer, Spring, and Fall (Closed in the winter)

Campsites: 221 (RVs permitted)

Accessibility: Yes, seven ADA sites are available

Located in the heart of the Shenandoah National Park, within proximity to all the top sites in the park, the Big Meadows Campground is an expansive campground perfect for a night in the park.

You’ll be close to the Bryd Visitor Center, Dark Hollow Falls, etc.

In early spring, it works on a first-come, first-serve basis, and with the onset of summer, you can make reservations, especially recommended on holidays and weekends.

All sites offer a picnic table, fire ring, ice, potable water, firewood, and other basic facilities and cost $30/night.

Loft Mountain Campground

Season: Late Spring, Summer, and Fall (Closed in the winter; until early May)

Campsites: 207 (RVs permitted)

Accessibility: Yes, two ADA sites are available

The largest campground in the park, the Loft Mountian Campground, is located on top of Big Flat Mountain in the park’s Southern region and close to some iconic waterfalls and trails.

It offers sites via reservation and first-come, first-serve basis, but reservations are recommended, especially in peak season.

All locations provide ice, potable water, firewood, and other basic facilities and cost $30/night.

Mathew Arm Campground

Season: Late Spring, Summer, and Fall (Closed in the winter; until early May)

Campsites: 165 (RVs permitted)

Accessibility: Yes, four ADA sites are available; however, no accessible shower and laundry amenities are present on site

Located near the Front Royal entrance in the park’s Northern region, the Mathew Arm Campground is just off Skyline Drive.

It is an excellent place to camp, especially in the fall; it offers sites via reservation and first-come, first-serve basis, though reservations are recommended.

All locations provide potable water, a fire ring, a picnic table, and Elkwallow Wayside (which is just two miles from the ground), and it costs $30/night.

Lewis Mountain Campground

Season: Spring, Summer, and Fall (closed in the winter)

Campsites: 30 (RVs permitted)

Accessibility: Yes, two ADA sites are available

The smallest campground in the national park, the Lewis Mountain Campground, is great if you’re looking for a more isolated place to camp for the night.

It’s close to top attractions in the park, like the Big Meadows Valley, and operates entirely on a first-come, first-serve basis.

Al sites offer ice, firewood, potable water, and other basic amenities and cost $30/night.

Parks Near Shenandoah National Park

Cedar Creek & Belle Grove National Historical Park

C&O Canal National Historical Park

Manassas National Battlefield Park

Appomattox Court House National Historical Park

Booker T Washington National Monument

Antietam National Battlefield

Check out all of the National Parks in Virginia along with National Parks in Kentucky, National Parks in Maryland, National Parks in North Carolina, Tennessee National Parks, and West Virginia National Parks